.303 British

| .303 British (7.7×56mm Rimmed) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Left to right: .303 British, 6.5×50mmSR Arisaka and .30-06 Springfield soft point ammunition | ||||||||||||||||

| Type | Rifle | |||||||||||||||

| Place of origin | United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||

| Service history | ||||||||||||||||

| In service | 1889–present | |||||||||||||||

| Used by | United Kingdom and many other countries | |||||||||||||||

| Wars |

| |||||||||||||||

| Production history | ||||||||||||||||

| Produced | 1889–present | |||||||||||||||

| Specifications | ||||||||||||||||

| Case type | Rimmed, bottleneck | |||||||||||||||

Bullet diameter | 7.92 mm (0.312 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Neck diameter | 8.64 mm (0.340 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Shoulder diameter | 10.19 mm (0.401 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Base diameter | 11.68 mm (0.460 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Rim diameter | 13.72 mm (0.540 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Rim thickness | 1.63 mm (0.064 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Case length | 56.44 mm (2.222 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Overall length | 78.11 mm (3.075 in) | |||||||||||||||

| Case capacity | 3.64 cm3 (56.2 gr H2O) | |||||||||||||||

Rifling twist | 254 mm (1-10 in) | |||||||||||||||

Primer type | Large rifle | |||||||||||||||

| Maximum pressure (C.I.P.) | 365.00 MPa (52,939 psi) | |||||||||||||||

| Maximum pressure (SAAMI) | 337.84 MPa (49,000 psi) | |||||||||||||||

| Maximum CUP | 45,000 CUP | |||||||||||||||

| Ballistic performance | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

Test barrel length: 24 Source(s): Accurate Powder[1] | ||||||||||||||||

The .303 British (designated as the 303 British by the C.I.P.[2] and SAAMI[3]) or 7.7×56mmR, is a .303-inch (7.7 mm) calibre (with the bore diameter measured between the lands as is common practice in Europe) rimmed rifle cartridge first developed in Britain as a black-powder round put into service in December 1888 for the Lee–Metford rifle. In 1891 the cartridge was adapted to use smokeless powder.[4] It was the standard British and Commonwealth military cartridge from 1889 until the 1950s when it was replaced by the 7.62×51mm NATO.[2]

Contents

1 Cartridge dimensions

2 Military use

2.1 History and development

2.2 Propellant

2.3 Projectile

2.4 Mark II – Mark VI

2.5 Mark VII

2.5.1 .276 Enfield

2.6 Mark VIII

2.7 Tracer, armour-piercing and incendiary

3 Military surplus ammunition

4 Headstamps and colour-coding

5 Japanese 7.7 mm ammunition

6 Civilian use

6.1 Commercial ammunition and reloading

6.2 Hunting use

7 The .303 British as parent case

7.1 .303 Epps

8 Firearms chambered for .303 British

9 See also

10 References

11 External links

Cartridge dimensions

The .303 British has 3.64 ml (56 grains H2O) cartridge case capacity. The pronounced tapering exterior shape of the case was designed to promote reliable case feeding and extraction in bolt action rifles and machine guns alike, under challenging conditions.

.303 British maximum C.I.P. cartridge dimensions. All sizes in millimeters (mm).

Americans would define the shoulder angle at alpha/2 ≈ 17 degrees. The common rifling twist rate for this cartridge is 254 mm (10.0 in) 10 in), 5 grooves, Ø lands = 7.70 millimetres (0.303 in), Ø grooves = 7.92 millimetres (0.312 in), land width = 2.12 millimetres (0.083 in) and the primer type is Berdan or Boxer (in large rifle size).

According to the official C.I.P. (Commission Internationale Permanente pour l'Epreuve des Armes à Feu Portatives) rulings the .303 British can handle up to 365.00 MPa (52,939 psi) Pmax piezo pressure. In C.I.P. regulated countries every rifle cartridge combo has to be proofed at 125% of this maximum C.I.P. pressure to certify for sale to consumers.[2]

This means that .303 British chambered arms in C.I.P. regulated countries are currently (2014) proof tested at 456.00 MPa (66,137 psi) PE piezo pressure.

The SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute) Maximum Average Pressure (MAP) for this cartridge is 49,000 psi (337.84 MPa) piezo pressure (45,000 CUP).[5]

The measurement .303-inch (7.70 mm) is the nominal size of the bore measured between the lands which follows the older black powder nomenclature. Measured between the grooves, the nominal size of the bore is .311-inch (7.90 mm). Bores for many .303 military surplus rifles are often found ranging from around .309-inch (7.85 mm) up to .318-inch (8.08 mm). Recommended bullet diameter for standard .303 British cartridges is .312-inch (7.92 mm).[6]

Military use

History and development

During a service life of over 70 years with the British Commonwealth armed forces the .303-inch cartridge in its ball pattern progressed through ten marks which eventually extended to a total of about 26 variations.[7]

The bolt thrust of the .303 British is relatively low compared to many other service rounds used in the early 20th century.

Propellant

The original .303 British service cartridge employed black powder as a propellant, and was adopted for the Lee–Metford rifle, which had rifling designed to lessen fouling from this propellant. The Lee–Metford was used as a trial platform by the British Committee on Explosives to experiment with many different smokeless powders then coming to market, including Ballistite, Cordite, and Rifleite.[8][9][10]Ballistite was a stick-type smokeless powder composed of soluble nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine.[10]Cordite was a stick-type or 'chopped' smokeless gunpowder composed of nitroglycerine, gun-cotton, and mineral jelly, while Rifleite was a true nitrocellulose powder, composed of soluble and insoluble nitrocellulose, phenyl amidazobense, and volatiles similar to French smokeless powders.[9][10] Unlike Cordite, Riflelite was a flake powder, and contained no nitroglycerine.[10] Excessive wear of the shallow Lee–Metford rifling with all smokeless powders then available caused ordnance authorities to institute a new type of barrel rifling designed by the RSAF, Enfield, to increase barrel life; the rifle was referred to thereafter as the Lee–Enfield.[8] After extensive testing, the Committee on Explosives selected Cordite for use in the Mark II .303 British service cartridge.[8]

Projectile

The initial .303 Mark I and Mk II service cartridges employed a 215-grain, round-nosed, copper-nickel full-metal-jacketed bullet with a lead core. After tests determined that the service bullet had too thin a jacket when used with cordite, the Mk II bullet was introduced, with a flat base and thicker copper-nickel jacket.[11]

Mark II – Mark VI

Longitudinal section of Mk VI ammunition 1904, showing the round nose bullet

The Mk II round-nosed bullet was found to be unsatisfactory when used in combat, particularly when compared to the dum-dum rounds issued in limited numbers in 1897 during the Chitral and Tirah expeditions of 1897/98 on the North West Frontier of India.[11] This led to the introduction of the Cartridge S.A. Ball .303 inch Cordite Mark III, basically the original 215-grain (13.9 g) bullet with the jacketing cut back to expose the lead in the nose.[11] Similar hollow-point bullets were used in the Mk IV and Mk V loadings, which were put into mass production. The design of the Mk IV hollow-point bullet shifted bullet weight rearwards, improving stability and accuracy over the regular round-nose bullet.[11] These soft-nosed and hollow-point bullets, while effective against human targets, had a tendency to shed the outer metal jacket upon firing; the latter occasionally stuck in the bore, causing a dangerous obstruction.[11] The Hague Convention of 1899[11] later declared that use of expanding bullets against signatories of the convention was inhumane, and as a result the Mk III, Mk IV, and Mk V were withdrawn from active service. The remaining stocks (over 45 million rounds) were used for target practice.

The concern about expanding bullets was brought up at the 1899 Hague Convention by Swiss and Dutch representatives. The Swiss were concerned about small arms ammunition that "increased suffering", and the Dutch focused on the British Mark III .303 loading in response to their treatment of Boer settlers in South Africa. The British and American defense was that they should not focus on specific bullet designs, like hollow-points, but instead on rounds that caused "superfluous injury". The parties in the end agreed to abstain from using expanding bullets. As a result, the Mark III and other expanding versions of the .303 were not issued during the Second Boer War (1899–1902). Boer guerrillas allegedly used expanding hunting ammunition against the British during the war, and New Zealand Commonwealth troops may have brought Mark III rounds with them privately after the Hague Convention without authorization.[12]

To replace the Mk III, IV, and V, the Mark VI round was introduced in 1904, using a round nose bullet similar to the Mk II, but with a thinner jacket designed to produce some expansion, though this proved not to be the case.[13][14]

Mark VII

Longitudinal section of Mk VII ammunition circa 1915, showing the "tail heavy" design

In 1898, APX (Atelier de Puteaux), with their "Balle D" design for the 8mm Lebel cartridge, revolutionised bullet design with the introduction of pointed "spitzer" rounds. In addition to being pointed, the bullet was also much lighter in order to deliver a higher muzzle velocity. It was found that as velocity increased the bullets suddenly became much more deadly.[15]

In 1910, the British took the opportunity to replace their Mk VI cartridge with a more modern design. The Mark VII loading used a 174 grains (11.3 g) pointed bullet with a flat-base. The .303 British Mark VII cartridge had a muzzle velocity of 2,440 ft/s (744 m/s) and a maximum range of approximately 3,000 yd (2,700 m).[4][16] The Mk VII was different from earlier .303 bullet designs or spitzer projectiles in general. Although it appears to be a conventional spitzer-shape full metal jacket bullet, this appearance is deceptive: its designers made the front third of the interior of the Mk 7 bullets out of aluminium (from Canada) or tenite (cellulosic plastic), wood pulp or compressed paper, instead of lead and they were autoclaved to prevent wound infection. This lighter nose shifted the centre of gravity of the bullet towards the rear, making it tail heavy. Although the bullet was stable in flight due to the gyroscopic forces imposed on it by the rifling of the barrel, it behaved very differently upon hitting the target. As soon as the bullet hit the target and decelerated, its heavier lead base caused it to pitch violently and deform, thereby inflicting more severe gunshot wounds than a standard single-core spitzer design.[17] In spite of this, the Mk VII bullet was legal due to the full metal jacket used according to the terms of the Hague Convention.

The Mk VII (and later Mk VIII) rounds have versions utilizing nitrocellulose flake powder smokeless propellants. The nitrocellulose versions—first introduced in World War I—were designated with a "Z" postfix indicated after the type (e.g. Mark VIIZ, with a weight of 175 grains) and in headstamps.[18]

.276 Enfield

.303 British cartridges, along with the Lee–Enfield rifle, were heavily criticized after the Second Boer War. Their heavy round-nosed bullets had low muzzle velocities and suffered compared to the 7×57mm rounds fired from the Mauser Model 1895. The high-velocity 7×57mm had a flatter trajectory and longer range that excelled on the open country of the South African plains. In 1910, work began on a long-range replacement cartridge, which emerged in 1912 as the .276 Enfield. The British also sought to replace the Lee–Enfield rifle with the Pattern 1913 Enfield rifle, based on the Mauser M98 bolt action design. Although the round had better ballistics, troop trials in 1913 revealed problems including excessive recoil, muzzle flash, barrel wear and overheating. Attempts were made to find a cooler-burning propellant, but further trials were halted in 1914 by the onset of World War I. As a result, the Lee–Enfield rifle was retained, and the .303 British cartridge (with the improved Mark VII loading) was kept in service.[19]

Mark VIII

In 1938 the Mark VIII (Mark VIII and Mark VIIIz) round was approved to obtain greater range from the Vickers machine gun.[20] Slightly heavier than Mk VII bullet at 175 grains (11.3 g), the primary difference was the addition of a boat-tail and more propellant (41 grains of nitrocellulose powder in the case of the Mk VIIIz), giving a muzzle velocity of 2,525–2,900 ft/s (770–884 m/s). As a result, the chamber pressure was significantly higher, at 42,000–60,000 lbf/sq in (approximately 280–414 MPa), depending upon loading, compared to the 39,000 lbf/sq in of the Mark VII round.[21] The Mark VIII cartridge had a maximum range of approximately 4,500 yd (4,115 m). Mk VIII ammunition was described as being for "All suitably-sighted .303-inch small arms and machine guns" but caused significant bore erosion in weapons formerly using Mk VII cordite, ascribed to the channelling effect of the boat-tail projectile. As a result, it was prohibited from general use with rifles and light machine guns except in emergency.[22] As a consequence of the official prohibition, ordnance personnel reported that every man that could get his hands on Mk VIII ammunition promptly used it in his own rifle.[20]

Tracer, armour-piercing and incendiary

Tracer and armour-piercing cartridges were introduced during 1915, with explosive Pomeroy bullets introduced as the Mark VII.Y in 1916.

Several incendiaries were privately developed from 1914 to counter the Zeppelin threat but none were approved until the Brock design late in 1916 as BIK Mark VII.K[23]Wing Cmdr. Frank Brock RNVR, its inventor, was a member of the Brock fireworks-making family. Anti-zeppelin missions typically used machine guns loaded with a mixture of Brock bullets containing potassium chlorate, Pomeroy bullets containing dynamite, and Buckingham bullets containing pyrophoric yellow phosphorus.[24] A later incendiary was known as the de Wilde, which had the advantage of leaving no visible trail when fired. The de Wilde was later used in some numbers in fighter guns during the 1940 Battle of Britain.[25]

These rounds were extensively developed over the years and saw several Mark numbers. The last tracer round introduced into British service was the G Mark 8 in 1945, the last armour-piercing round was the W Mark 1Z in 1945 and the last incendiary round was the B Mark 7 in 1942. Explosive bullets were not produced in the UK after 1933 due to the relatively small amount of explosive that could be contained in the bullet, limiting their effectiveness, their role being taken by the use of Mark 6 and 7 incendiary bullets.

In 1935 the .303 O Mark 1 Observing round was introduced for use in machine guns. The bullet to this round was designed to break up with a puff of smoke on impact. The later Mark 6 and 7 incendiary rounds could also be used in this role.

During World War I British factories alone produced 7,000,000,000 rounds of .303 ammunition. Factories in other countries added greatly to this total.[26]

Military surplus ammunition

Military surplus .303 British ammunition that may be available often has corrosive primers, given the mass manufacture of the cartridge predates Commonwealth adoption of non-corrosive primers concurrent with the adoption of 7.62 NATO in 1955. There is no problem with using ammunition loaded with corrosive primers, providing that the gun is thoroughly cleaned after use to remove the corrosive salts. The safe method for all shooters of military surplus ammunition is to assume the cartridge is corrosively primed unless certain otherwise.

Care must be taken to identify the round properly before purchase or loading into weapons.[according to whom?] Cartridges with the Roman numeral VIII on the headstamp are the Mark 8 round, specifically designed for use in Vickers machine guns. Although Mark 8 ammunition works well in a Vickers gun, it should not be used in rifles because the cordite powder causes increased barrel wear. The boat-tailed bullet design of Mk 8 ammunition is not in itself a problem. However, when combined with the cordite propellant used in Mk 8 cartridges, which burns at a much higher temperature than nitrocellulose, there is increased barrel erosion. The cumulative effects of firing Mk 8 ammunition through rifles were known during the Second World War, and British riflemen were ordered to avoid using it, except in emergencies. The best general-purpose ammunition for any .303 military rifle is the Mark 7 design because it provides the best combination of accuracy and stopping power.[citation needed]

Headstamps and colour-coding

.303 British Cartridge (Mk VII), manufactured by CAC in 1945

| Headstamp ID | Primer Annulus Colour | Bullet Tip Colour | Other Features | Functional Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VII or VIIZ | Purple | None | None | Ball |

| VIIIZ | Purple | None | None | Ball |

| G1, G2, G3, G7 or G8 | Red | None | None | Tracer |

| G4, G4Z, G6 or G6Z | Red | White | None | Tracer |

| G5 or G5Z | Red | Gray | None | Tracer |

| W1 or W1Z | Green | None | None | Armour-Piercing |

| VIIF or VIIFZ | None | None | None | Semi-Armour Piercing (1916-1918) |

| F1 | Green | None | None | Semi-Armour Piercing (1941) |

| B4 or B4Z | Blue | None | Step in bullet jacket | Incendiary |

| B6 or B6Z | Blue | None | None | Incendiary |

| B7 or B7Z | Blue | Blue | None | Incendiary |

| O.1 | Black | Black | None | Observing |

| PG1 or PG1Z | Red | None | Blue band on case base | Practice-Tracer |

| H1Z | None | None | Front half of case blackened | Grenade Discharger |

| H2 | None | None | Entire case blackened | Grenade Discharger |

| H4 | None | None | Case blackened 3/4" inch from each end | Grenade Discharger |

| H7Z | None | None | Rear Half of case blackened | Grenade Discharger (v.powerful load) |

Japanese 7.7 mm ammunition

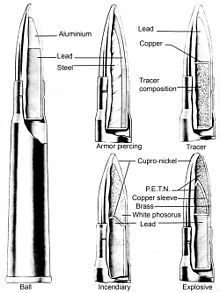

Cutaways of the five types of ammunition produced in Japan.

Japan produced a number of machine guns that were direct copies of the British Lewis (Japanese Type 92 machine gun) and Vickers machine guns including the ammunition. These were primarily used in Navy aircraft. The 7.7mm cartridge used by the Japanese versions of the British guns is a direct copy of the .303 British (7.7×56mmR) rimmed cartridge and is distinctly different from the 7.7×58mm Arisaka rimless and 7.7×58mm Type 92 semi-rimmed cartridges used in other Japanese machine guns and rifles.[27]

Ball: 174 grains (11.3 g). Cupro-Nickel jacket with a composite aluminium/lead core. Black primer.

Armour-Piercing.: Brass jacket with a steel core. White primer.

Tracer: 130 grains (8.4 g). Cupro-Nickel jacket with a lead core. Red primer.

Incendiary: 133 grains (8.6 g). Brass jacket with white phosphorus and lead core. Green primer.

H.E.: Copper jacket with a PETN and lead core. Purple primer.

Note: standard Japanese ball ammunition was very similar to the British Mk 7 cartridge. The two had identical bullet weights and a "tail-heavy" design, as can be seen in the cut-away diagram.

Civilian use

The .303 cartridge has seen much sporting use with surplus military rifles, especially in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and to a lesser extent, in the United States and South Africa. In Canada, it was found to be adequate for any game except the great bears. In Australia, it was common for military rifles to be re-barreled in .303/25 and .303/22. However the .303 round still retains a considerable following as a game cartridge for all game species, especially Sambar deer in wooded country. A recent change.org petition seeking Lithgow Arms to chamber the LA102 centerfires rifle in .303 as a special edition release has attracted considerable attention both in Australia and worldwide. In South Africa .303 British Lee–Enfield rifles captured by the Boers during the Boer War were adapted for sporting purposes and became popular with many hunters of non-dangerous game, being regarded as adequate for anything from the relatively small impala, to the massive eland and kudu.[28]

Commercial ammunition and reloading

Commercial soft point .303 British loaded in a Lee–Enfield five-round charger.

Civilian soft point .303 ammunition, suitable for hunting purposes.

The .303 British is one of the few (along with the .22 Hornet, .30-30 Winchester, and 7.62×54mmR) bottlenecked, rimmed centerfire rifle cartridges still in common use today. Most of the bottleneck rimmed cartridges of the late 1880s and 1890s fell into disuse by the end of the First World War.

Commercial ammunition for weapons chambered in .303 British is readily available, as the cartridge is still manufactured by major producers such as Remington, Federal, Winchester, Sellier & Bellot, Prvi Partizan and Wolf. Commercially produced ammunition is widely available in various full metal jacket bullet, soft point, hollow point, flat-based and boat tail designs—both spitzer and round-nosed.

Reloading equipment and ammunition components are also manufactured by several companies. Dies and other tools for the reloading of .303 British are produced by Forster, Hornady, Lee, Lyman, RCBS, and Redding. Depending on the bore and bore erosion a reloader may choose to utilize bullet diameters of .308–.312" with .311" or .312" diameter bullets being the most common. Bullets specifically produced and sold for reloading .303 British are made by Sierra, Hornady, Speer, Woodleigh, Barnes, and Remington. Where extreme accuracy is required, the Sierra Matchking 174-grain (11.3 g) HPBT bullet is a popular choice. Sierra does not advocate use of Matchking brand bullets for hunting applications. For hunting applications, Sierra produces the ProHunter in .311" diameter. The increasingly popular all-copper Barnes TSX is now available in the .311" diameter as a 150 gr projectile which is recommended by Barnes for hunting applications.

With most rifles chambered in .303 British being of military origin, success in reloading the calibre depends on the reloader's ability to compensate for the often loose chamber of the rifle. Reduced charge loads and neck sizing are two unanimous recommendations from experienced loaders of .303 British to newcomers to the calibre. The classic 174-grain (11.3 g) FMJ bullets are widely available, though purchasers may wish to check whether or not these feature the tail-heavy Mk 7 design. In any case other bullet weights are available, e.g. 150, 160, 170, 180, and 200-grain (13 g), both for hunting and target purposes.

Hunting use

The .303 British cartridge is suitable for all medium-sized game and is an excellent choice for whitetail deer and black bear hunting. In Canada it was a popular moose and deer cartridge when military surplus rifles were available and cheap; it is still used. The .303 British can offer very good penetrating ability due to a fast twist rate that enables it to fire long, heavy bullets with a high sectional density. Canadian Rangers use it for survival and polar bear protection. In 2015, the Canadian Rangers began the process to evaluate rifles chambered for .308 Winchester, as the Canadian Department of National Defence expects the currently issued Lee–Enfield No. 4 rifles will soon be very difficult if not impossible to maintain due to parts scarcity.[29]

The .303 British as parent case

.303 Epps

Canadian Ellwood Epps, founder of Epps Sporting Goods, created an improved version of the .303 British. It has better ballistic performance than the standard .303 British cartridge. This is accomplished by increasing the shoulder angle from 16 to 35 degrees, and reducing the case taper from .062 inches to .009 inches. These changes increase the case's internal volume by approximately 9%. The increased shoulder angle and reduced case taper eliminate the drooping shoulders of the original .303 British case, which, combined with reaming the chamber to .303 Epps, improves case life.[30]

Firearms chambered for .303 British

- Bren light machine gun

Browning Model 1919 machine gun aircraft version- BSA Autorifle

- Canadian Ross Rifle Mk I through III

- Caldwell machine gun

- Charlton Automatic Rifle

- Farquharson rifle

- Hotchkiss .303 Mk I & I*

- Huot automatic rifle

- Jungle Carbine

Lee–Enfield rifle

Lee–Metford rifle- Lewis gun

Martini–Enfield rifle- McCrudden light machine rifle

Parker Hale Sporter Rifle- P14 rifle

- Ruger No. 1

- Thorneycroft carbine

Vickers-Berthier light machine gun- Vickers machine gun

- Vickers K machine gun

- Winchester Model 1895

See also

- British military rifles

- Caliber conversion sleeve

- List of rifle cartridges

- Table of handgun and rifle cartridges

- .303 Savage

- .303 Magnum

- .30-06 Springfield

- .308 Winchester

7 mm caliber (overview of cartridges)

References

^ ".303 British" (PDF). Accurate Powder. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2008..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc C.I.P. TDCC datasheet 303 British

^ "SAAMI Drawing 303 British" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

^ ab David Cushman. "History of the .303 British Calibre Service Ammunition Round".

^ ANSI/SAAMI Velocity & Pressure Data: Centerfire Rifle Archived 15 July 2013 at WebCite

^ Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, Rifle-Pistol, Third Edition, Hornady Manufacturing Company, 1980, 1985, p.253-254.

^ Temple, B. A., Identification Manual of the .303 British Service Cartridge - No: 1 - BALL AMMUNITION, Don Finlay (Printer 1986), p. 1.

ISBN 0-9596677-2-5

^ abc Chisholm, Hugh, Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Co., Vol. 23, (1911) p. 327

^ ab Sanford, Percy Gerald, Nitro-explosives: a Practical treatise Concerning the Properties, Manufacture, and Analysis of Nitrated Substances, London: Crosby Lockwood & Son (1896) pp. 166-173, 179

^ abcd Walke, Willoughby (Lt.), Lectures on Explosives: A Course of Lectures Prepared Especially as a Manual and Guide in the Laboratory of the U.S. Artillery School, J. Wiley & Sons (1897) pp. 336-343

^ abcdef Ommundsen, Harcourt, and Robinson, Ernest H., Rifles and Ammunition Shooting, New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co. (1915), p. 117-119

^ A Way Forward in Contemporary Understanding of the 1899 Hague Declaration on Expanding Bullets - SAdefensejournal.com, 7 October 2013

^ "REJECTED MARK IV. BULLETS".

^ "Dum Dums". Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

^ 8x50R Lebel (8mm Lebel)

^ "Rifle, Short Magazine Lee–Enfield". The Lee–Enfield Rifle Website. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

^ "The Deadly .303 British and The Box O' Truth". Box of Truth website. 2014-06-13.

[self-published source]

^ "The .303 British Cartridge". Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

^ "The .256 Inch British: A Lost Opportunity" Archived 6 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. by Anthony G Williams

^ ab Dunlap, Roy F., Ordnance Went Up Front, Samworth Press (1948), p. 40.

ISBN 978-1-884849-09-1

^ Dunlap, Roy F., Ordnance Went Up Front, Samworth Press (1948),

ISBN 978-1-884849-09-1 p. 40: There appear to have been two distinct loadings of the Mark VIII cartridge: one small arms expert serving with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps at Dekheila noted that Mk VIIIz ammunition he examined had a claimed muzzle velocity of 2,900 ft/s (880 m/s), furthermore, primers on MK VIII fired cases he examined looked "painted on", normally indicating a pressure of around 60,000 lbs. per square inch.

^ Temple, B.A. Identification Manual on the .303 British Service Cartridge No.1 - Ball Ammunition.

^

Labbett, P.; Mead, P.J.F (1988). "Chapter 5, .303 inch Incendiary, Explosive and Observing Ammunition". .303 inch: a history of the .303 cartridge in British Service. authors. ISBN 978-0-9512922-0-4.

^ "The Brock Bullet Claim" (PDF). flightglobal.com. Flight Aircraft Engineer Magazine. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

^ The Battle of Britain - Excerpts from an Historic Despatch by Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding,Flight, 19 September 1946, p323

^

Featherstone-Haugh, JJ. (1973). "Appendix VII, page IV, "British Military Output WWI"". Home Front - Untold Tales of British Workers during the Great Wars. OUP.

^ Walter H.B. Smith, Small Arms of the World, Stackpole Publications.

^ Hawks, Chuck. "Matching the Gun to the Game". ChuckHawks.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

^ http://ottawacitizen.com/news/national/defence-watch/here-it-is-the-new-sako-rifle-for-the-canadian-rangers Here it is – the new Sako rifle for the Canadian Rangers

^ "303 Epps - Notes on Improved Cases". Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to .303 British. |

"Photos of the contents of different .303 British cartridges". Box of Truth website. 2014-06-13.

"Photo of Sellier & Bellot 150 gr (9.7 g) .303 British soft-point fired into ballistic gelatin (bullet travelled right to left)". Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

"Photos of various different types of .303 ammunition".

"Africa". Sniper Central. Archived from the original on 2006-03-14.

".303 British". 303british.com.

David Cushman. "Headstamps of various .303 ammunition producers".

- 7,7 x 56 R Tipo 89 Giapponese

- C.I.P. TDCC datasheet .303 British

- SAAMI Drawing 303 British