Hamdan ibn Hamdun

Hamdan ibn Hamdun ibn al-Harith al-Taghlibi (fl. 868–895) was a Taghlibi Arab chieftain in the Jazira, and the patriarch of the Hamdanid dynasty. Alongside other Arab chieftains of the area, he resisted the attempts at re-imposition of Abbasid control over the Jazira in the 880s, and joined the Kharijite Rebellion. He was finally defeated and captured by Caliph al-Mu'tadid in 895, but was later released as a reward for the distinguished services of his son Husayn to the Caliph.

Life

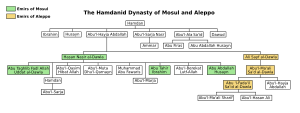

Family tree of the Hamdanid dynasty

His family belonged to the Banu Taghlib tribe, established in the Jazira since before the Muslim conquests. The tribe was particularly strong in the region of Mosul, and came to dominate the area during the decade-long Anarchy at Samarra (861–870), when the Taghlibi leaders took advantage of the collapse of the authority of the central Abbasid government to assert their autonomy.[1] Hamdan himself appears for the first time in 868, fighting alongside other Taghlibis against the Kharijite Rebellion in the Jazira.[2]

In 879, however, the Abbasid government, in an effort to restore its control, replaced the succession of Tahglibi chieftains as governors of Mosul by a Turkish commander, Ishaq ibn Kundajiq. This prompted the defection of the Taghlib chiefs, including Hamdan ibn Hamdun, to the Kharijite rebels.[2][3] Hamdan became a prominent leader in the rebellion; thus he is mentioned—with the Kharijite sobriquet of "al-Shari"—among the Kharijite and Arab tribal leaders in the great victory won by Ibn Kundajiq in April/May 881, when the rebel army was routed and pursued to Nisibis and Amid.[2][4]

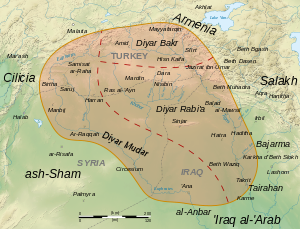

Map of the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia)

In 892, a new Caliph, al-Mu'tadid, took the throne, determined to restore Abbasid control over the Jazira. In a series of campaigns, he achieved the submission of most local potentates, but Hamdan offered tenacious opposition. Holding the fortresses of Maridin and Ardamusht (near modern Cizre), and allied with the Kurdish tribes of the mountains north of the Jaziran plain, he held out until 895. In that year, the Caliph took first Mardin and then Ardamusht, which was yielded by Hamdan's son Husayn. Hamdan fled before the caliphal army, but after an "epic chase" (H. Kennedy), finally gave up and surrendered himself at Mosul and was thrown in prison.[2][3]

As H. Kennedy comments, "this surrender might have seemed the end of the family fortunes as it was for other local leaders in the area", but Hamdan's son, Husayn managed to preserve the family's fortunes. Husayn entered the Caliph's service and was instrumental in ending the Kharijite Rebellion and capturing its leader, Harun al-Shari. He was rewarded by the grateful Mu'tadid with a pardon for his father and the right to raise and command his own corps of Taghlibi horse, which he led on several expeditions over the next few years, becoming one of the Caliphate's most prominent commanders. His influence enabled him to become, in Kennedy's description, the "intermediary between government and the Arabs and Kurds of the Jazira", thereby cementing the family's dominance in the area and laying the foundation for the rise of the Hamdanid dynasty to power under his two nephews, Nasir al-Dawla and Sayf al-Dawla.[5][6]

References

^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 265–266.

^ abcd Canard 1971, p. 126.

^ ab Kennedy 2004, p. 266.

^ Fields 1987, p. 50.

^ Canard 1971, pp. 126ff..

^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 266ff..

Sources

Canard, Marius (1971). "Ḥamdānids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 126–131. ISBN 90-04-08118-6..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Fields, Philip M., ed. (1987). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume 37: The ʿAbbāsid Recovery: The War Against the Zanj Ends, A.D. 879–893/A.H. 266–279. SUNY series in Near Eastern studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-054-0.

Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 0-582-40525-4.