Republicanism

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

Central concepts

|

Schools

|

Types of republics

|

Important thinkers

|

History

|

By country

|

Related topics

|

.mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal} Politics portal |

Republicanism is a political ideology centred on citizenship in a state organized as a republic under which the people hold popular sovereignty. Many countries are "republics" in the sense that they are not monarchies.

The word "republic" derives from the Latin noun-phrase res publica, which referred to the system of government that emerged in the 6th century BCE following the expulsion of the kings from Rome by Lucius Junius Brutus and Collatinus.[1]

This form of government in the Roman state collapsed in the latter part of the 1st century BCE, giving way to what was a monarchy in form, if not in name. Republics recurred subsequently, with, for example, Renaissance Florence or early modern Britain. The concept of a republic became a powerful force in Britain's North American colonies, where it contributed to the American Revolution. In Europe, it gained enormous influence through the French Revolution and through the First French Republic of 1792–1804.

Contents

1 Historical development of republicanism

1.1 Classical antecedents

1.1.1 Ancient Greece

1.1.2 Ancient Rome

1.2 Renaissance republicanism

1.2.1 Dutch Republic

1.2.2 Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

1.3 Enlightenment republicanism

1.3.1 England

1.3.2 French and Swiss thought

1.4 Republicanism in the United States

1.5 Républicanisme

1.6 Republicanism in Ireland

2 Modern republicanism

2.1 France

2.2 United States

2.3 The British Empire and the Commonwealth of Nations

2.3.1 Australia

2.3.2 Barbados

2.3.3 Canada

2.3.4 Jamaica

2.3.5 New Zealand

2.3.6 The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

2.4 The Netherlands

2.5 Sweden

2.6 Spain

2.7 Neo-republicanism

3 Democracy

3.1 Democracy and republic

3.2 Constitutional monarchs and upper chambers

4 See also

5 References

6 Further reading

6.1 General

6.2 Europe

6.3 United States

7 External links

Historical development of republicanism

Classical antecedents

Ancient Greece

In Ancient Greece, several philosophers and historians analyzed and described elements we now recognize as classical republicanism. Traditionally, the Greek concept of "politeia" was rendered into Latin as res publica. Consequently, political theory until relatively recently often used republic in the general sense of "regime". There is no single written expression or definition from this era that exactly corresponds with a modern understanding of the term "republic" but most of the essential features of the modern definition are present in the works of Plato, Aristotle, and Polybius. These include theories of mixed government and of civic virtue. For example, in The Republic, Plato places great emphasis on the importance of civic virtue (aiming for the good) together with personal virtue ('just man') on the part of the ideal rulers. Indeed, in Book V, Plato asserts that until rulers have the nature of philosophers (Socrates) or philosophers become the rulers, there can be no civic peace or happiness.[2]

A number of Ancient Greek city-states such as Athens and Sparta have been classified as "classical republics", because they featured extensive participation by the citizens in legislation and political decision-making. Aristotle considered Carthage to have been a republic as it had a political system similar to that of some of the Greek cities, notably Sparta, but avoided some of the defects that affected them.

Ancient Rome

Both Livy, a Roman historian, and Plutarch, who is noted for his biographies and moral essays, described how Rome had developed its legislation, notably the transition from a kingdom to a republic, by following the example of the Greeks. Some of this history, composed more than 500 years after the events, with scant written sources to rely on, may be fictitious reconstruction.

The Greek historian Polybius, writing in the mid-2nd century BCE, emphasized (in Book 6) the role played by the Roman Republic as an institutional form in the dramatic rise of Rome's hegemony over the Mediterranean. Polybius exerted a great influence on Cicero as he wrote his politico-philosophical works in the 1st century BCE. In one of these works, De re publica, Cicero linked the Roman concept of res publica to the Greek politeia.

The modern term "republic", despite its derivation, is not synonymous with the Roman res publica. Among the several meanings of the term res publica, it is most often translated "republic" where the Latin expression refers to the Roman state, and its form of government, between the era of the Kings and the era of the Emperors. This Roman Republic would, by a modern understanding of the word, still be defined as a true republic, even if not coinciding entirely. Thus, Enlightenment philosophers saw the Roman Republic as an ideal system because it included features like a systematic separation of powers.

Romans still called their state "Res Publica" in the era of the early emperors because, on the surface, the organization of the state had been preserved by the first emperors without significant alteration. Several offices from the Republican era, held by individuals, were combined under the control of a single person. These changes became permanent, and gradually conferred sovereignty on the Emperor.

Cicero's description of the ideal state, in De re Publica, does not equate to a modern-day "republic"; it is more like enlightened absolutism. His philosophical works were influential when Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire developed their political concepts.

In its classical meaning, a republic was any stable well-governed political community. Both Plato and Aristotle identified three forms of government: democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy. First Plato and Aristotle, and then Polybius and Cicero, held that the ideal republic is a mixture of these three forms of government. The writers of the Renaissance embraced this notion.

Cicero expressed reservations concerning the republican form of government. While in his theoretical works he defended monarchy, or at least a mixed monarchy/oligarchy, in his own political life, he generally opposed men, like Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, and Octavian, who were trying to realise such ideals. Eventually, that opposition led to his death and Cicero can be seen as a victim of his own Republican ideals.

Tacitus, a contemporary of Plutarch, was not concerned with whether a form of government could be analyzed as a "republic" or a "monarchy".[3] He analyzed how the powers accumulated by the early Julio-Claudian dynasty were all given by a State that was still notionally a republic. Nor was the Roman Republic "forced" to give away these powers: it did so freely and reasonably, certainly in Augustus' case, because of his many services to the state, freeing it from civil wars and disorder.

Tacitus was one of the first to ask whether such powers were given to the head of state because the citizens wanted to give them, or whether they were given for other reasons (for example, because one had a deified ancestor). The latter case led more easily to abuses of power. In Tacitus' opinion, the trend away from a true republic was irreversible only when Tiberius established power, shortly after Augustus' death in 14 CE (much later than most historians place the start of the Imperial form of government in Rome). By this time, too many principles defining some powers as "untouchable" had been implemented.[4]

Renaissance republicanism

In Europe, republicanism was revived in the late Middle Ages when a number of states, which arose from medieval communes, embraced a republican system of government.[5] These were generally small but wealthy trading states in which the merchant class had risen to prominence. Haakonssen notes that by the Renaissance, Europe was divided, such that those states controlled by a landed elite were monarchies, and those controlled by a commercial elite were republics. The latter included the Italian city-states of Florence, Genoa, and Venice and members of the Hanseatic League. One notable exception was Dithmarschen, a group of largely autonomous villages, who confederated in a peasants' republic. Building upon concepts of medieval feudalism, Renaissance scholars used the ideas of the ancient world to advance their view of an ideal government. Thus the republicanism developed during the Renaissance is known as 'classical republicanism' because it relied on classical models. This terminology was developed by Zera Fink in the 1960s,[6] but some modern scholars, such as Brugger, consider it confuses the "classical republic" with the system of government used in the ancient world.[7] 'Early modern republicanism' has been proposed as an alternative term. It is also sometimes called civic humanism. Beyond simply a non-monarchy, early modern thinkers conceived of an ideal republic, in which mixed government was an important element, and the notion that virtue and the common good were central to good government. Republicanism also developed its own distinct view of liberty.

Renaissance authors who spoke highly of republics were rarely critical of monarchies. While Niccolò Machiavelli's Discourses on Livy is the period's key work on republics, he also wrote the treatise The Prince, which is better remembered and more widely read, on how best to run a monarchy. The early modern writers did not see the republican model as universally applicable; most thought that it could be successful only in very small and highly urbanized city-states. Jean Bodin in Six Books of the Commonwealth (1576) identified monarchy with republic.[8]

Classical writers like Tacitus, and Renaissance writers like Machiavelli tried to avoid an outspoken preference for one government system or another. Enlightenment philosophers, on the other hand, expressed a clear opinion. Thomas More, writing before the Age of Enlightenment, was too outspoken for the reigning king's taste, even though he coded his political preferences in a utopian allegory.

In England a type of republicanism evolved that was not wholly opposed to monarchy; thinkers such as Thomas More and Sir Thomas Smith saw a monarchy, firmly constrained by law, as compatible with republicanism.

Dutch Republic

Anti-monarchism became more strident in the Dutch Republic during and after the Eighty Years' War, which began in 1568. This anti-monarchism was more propaganda than a political philosophy; most of the anti-monarchist works appeared in the form of widely distributed pamphlets. This evolved into a systematic critique of monarchy, written by men such as the brothers Johan and Peter de la Court. They saw all monarchies as illegitimate tyrannies that were inherently corrupt. These authors were more concerned with preventing the position of Stadholder from evolving into a monarchy, than with attacking their former rulers. Dutch republicanism also influenced on French Huguenots during the Wars of Religion. In the other states of early modern Europe republicanism was more moderate.[9]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, republicanism was the influential ideology. After the establishment of the Commonwealth of Two Nations, republicans supported the status quo, of having a very weak monarch, and opposed those who thought a stronger monarchy was needed. These mostly Polish republicans, such as Łukasz Górnicki, Andrzej Wolan, and Stanisław Konarski, were well read in classical and Renaissance texts and firmly believed that their state was a republic on the Roman model, and started to call their state the Rzeczpospolita. Atypically, Polish–Lithuanian republicanism was not the ideology of the commercial class, but rather of the landed nobility, which would lose power if the monarchy were expanded. This resulted in an oligarchy of the great landed magnates.[10]

Enlightenment republicanism

England

Oliver Cromwell set up a republic called the Commonwealth of England (1649–1660) which he ruled after the overthrow of King Charles I. James Harrington was then a leading philosopher of republicanism. John Milton was another important Republican thinker at this time, expressing his views in political tracts as well as through poetry and prose. In his epic poem Paradise Lost, for instance, Milton uses Satan’s fall to suggest that unfit monarchs should be brought to justice, and that such issues extend beyond the constraints of one nation.[11] As Christopher N. Warren argues, Milton offers “a language to critique imperialism, to question the legitimacy of dictators, to defend free international discourse, to fight unjust property relations, and to forge new political bonds across national lines.”[12] This form of international Miltonic republicanism has been influential on later thinkers including 19th-century radicals Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, according to Warren and other historians.[13][14]

The collapse of the Commonwealth of England in 1660 and the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II discredited republicanism among England's ruling circles. Nevertheless, they welcomed the liberalism, and emphasis on rights, of John Locke, which played a major role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Even so, republicanism flourished in the "country" party of the early 18th century (commonwealthmen), which denounced the corruption of the "court" party, producing a political theory that heavily influenced the American colonists. In general, the English ruling classes of the 18th century vehemently opposed republicanism, typified by the attacks on John Wilkes, and especially on the American Revolution and the French Revolution.[15]

French and Swiss thought

French and Swiss Enlightenment thinkers, such as Baron Charles de Montesquieu and later Jean-Jacques Rousseau, expanded upon and altered the ideas of what an ideal republic should be: some of their new ideas were scarcely traceable to antiquity or the Renaissance thinkers. Concepts they contributed, or heavily elaborated, were social contract, positive law, and mixed government. They also borrowed from, and distinguished republicanism from, the ideas of liberalism that were developing at the same time.

Liberalism and republicanism were frequently conflated during this period, because they both opposed absolute monarchy. Modern scholars see them as two distinct streams that both contributed to the democratic ideals of the modern world. An important distinction is that, while republicanism stressed the importance of civic virtue and the common good, liberalism was based on economics and individualism. It is clearest in the matter of private property, which, according to some, can be maintained only under the protection of established positive law.

Jules Ferry, Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1885, followed both these schools of thought. He eventually enacted the Ferry Laws, which he intended to overturn the Falloux Laws by embracing the anti-clerical thinking of the Philosophs. These laws ended the Catholic Church's involvement in many government institutions in late 19th-century France, including schools.

Republicanism in the United States

In recent years a debate has developed over the role of republicanism in the American Revolution and in the British radicalism of the 18th century. For many decades the consensus was that liberalism, especially that of John Locke, was paramount and that republicanism had a distinctly secondary role.[16]

The new interpretations were pioneered by J.G.A. Pocock, who argued in The Machiavellian Moment (1975) that, at least in the early 18th century, republican ideas were just as important as liberal ones. Pocock's view is now widely accepted.[17]Bernard Bailyn and Gordon Wood pioneered the argument that the American founding fathers were more influenced by republicanism than they were by liberalism. Cornell University professor Isaac Kramnick, on the other hand, argues that Americans have always been highly individualistic and therefore Lockean.[18]Joyce Appleby has argued similarly for the Lockean influence on America.

In the decades before the American Revolution (1776), the intellectual and political leaders of the colonies studied history intently, looking for models of good government. They especially followed the development of republican ideas in England.[19] Pocock explained the intellectual sources in America:[20]

The Whig canon and the neo-Harringtonians, John Milton, James Harrington and Sidney, Trenchard, Gordon and Bolingbroke, together with the Greek, Roman, and Renaissance masters of the tradition as far as Montesquieu, formed the authoritative literature of this culture; and its values and concepts were those with which we have grown familiar: a civic and patriot ideal in which the personality was founded in property, perfected in citizenship but perpetually threatened by corruption; government figuring paradoxically as the principal source of corruption and operating through such means as patronage, faction, standing armies (opposed to the ideal of the militia), established churches (opposed to the Puritan and deist modes of American religion) and the promotion of a monied interest – though the formulation of this last concept was somewhat hindered by the keen desire for readily available paper credit common in colonies of settlement. A neoclassical politics provided both the ethos of the elites and the rhetoric of the upwardly mobile, and accounts for the singular cultural and intellectual homogeneity of the Founding Fathers and their generation.

The commitment of most Americans to these republican values made the American Revolution inevitable. Britain was increasingly seen as corrupt and hostile to republicanism, and as a threat to the established liberties the Americans enjoyed.[21]

Leopold von Ranke in 1848 claimed that American republicanism played a crucial role in the development of European liberalism:[22]

By abandoning English constitutionalism and creating a new republic based on the rights of the individual, the North Americans introduced a new force in the world. Ideas spread most rapidly when they have found adequate concrete expression. Thus republicanism entered our Romanic/Germanic world.... Up to this point, the conviction had prevailed in Europe that monarchy best served the interests of the nation. Now the idea spread that the nation should govern itself. But only after a state had actually been formed on the basis of the theory of representation did the full significance of this idea become clear. All later revolutionary movements have this same goal... This was the complete reversal of a principle. Until then, a king who ruled by the grace of God had been the center around which everything turned. Now the idea emerged that power should come from below.... These two principles are like two opposite poles, and it is the conflict between them that determines the course of the modern world. In Europe the conflict between them had not yet taken on concrete form; with the French Revolution it did.

Républicanisme

Republicanism, especially that of Rousseau, played a central role in the French Revolution and foreshadowed modern republicanism. The revolutionaries, after overthrowing the French monarchy in the 1790s, began by setting up a republic; Napoleon converted it into an Empire with a new aristocracy. In the 1830s Belgium adopted some of the innovations of the progressive political philosophers of the Enlightenment.

Républicanisme is a French version of modern republicanism. It is a form of social contract, deduced from Jean-Jacques Rousseau's idea of a general will. Ideally, each citizen is engaged in a direct relationship with the state, removing the need for identity politics based on local, religious, or racial identification.

Républicanisme, in theory, makes anti-discrimination laws unnecessary, but some critics argue that colour-blind laws serve to perpetuate discrimination.[23]

Republicanism in Ireland

Inspired by the American and French Revolutions, the Society of United Irishmen was founded in 1791 in Belfast and Dublin. The inaugural meeting of the United Irishmen in Belfast on 18 October 1791 approved a declaration of the society's objectives. It identified the central grievance that Ireland had no national government: "...we are ruled by Englishmen, and the servants of Englishmen, whose object is the interest of another country, whose instrument is corruption, and whose strength is the weakness of Ireland..."[24] They adopted three central positions: (i) to seek out a cordial union among all the people of Ireland, to maintain that balance essential to preserve liberties and extend commerce; (ii) that the sole constitutional mode by which English influence can be opposed, is by a complete and radical reform of the representation of the people in Parliament; (iii) that no reform is practicable or efficacious, or just which shall not include Irishmen of every religious persuasion. The declaration, then, urged constitutional reform, union among Irish people and the removal of all religious disqualifications.

The event that above all[peacock term] influenced men's thoughts at that time was the French Revolution.[original research?] Public interest, already strongly aroused, was brought to a pitch by the publication in 1790 of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, and Thomas Paine's response, Rights of Man, in February 1791.[citation needed] Theobald Wolfe Tone wrote later that, "This controversy, and the gigantic event which gave rise to it, changed in an instant the politics of Ireland."[25] Paine himself was aware of this commenting on sales of Part I of Rights of Man in November 1791, only eight months after publication of the first edition, he informed a friend that in England "almost sixteen thousand has gone off – and in Ireland above forty thousand".[26] Paine my have been inclined to talk up sales of his works but what is striking in this context is that Paine believed that Irish sales were so far ahead of English ones before Part II had appeared. On 5 June 1792, Thomas Paine, author of the Rights of Man was proposed for honorary membership of the Dublin Society of the United Irishmen.[27]

The fall of the Bastille was to be celebrated in Belfast on 14 July 1791 by a Volunteer meeting. At the request of Thomas Russell, Tone drafted suitable resolutions for the occasion, including one favouring the inclusion of Catholics in any reforms. In a covering letter to Russell, Tone wrote, "I have not said one word that looks like a wish for separation, though I give it to you and your friends as my most decided opinion that such an event would be a regeneration of their country".[25] By 1795, Tone's Republicanism and that of the society had openly crystallized when he tells us: "I remember particularly two days thae we passed on Cave Hill. On the first Russell, Neilson, Simms, McCracken and one or two more of us, on the summit of McArt's fort, took a solemn obligation...never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country and asserted her independence."[28]

The culmination was an uprising against British rule in Ireland lasting from May to September 1798 – the Irish Rebellion of 1798 – with military support from revolutionary France in August and again October 1798. After the failure of the rising of 1798 the United Irishman, John Daly Burk, an émigré in the United States in his The History of the Late War in Ireland written in 1799, was most emphatic in its identification of the Irish, French and American causes.[29]

Modern republicanism

During the Enlightenment, anti-monarchism extended beyond the civic humanism of the Renaissance. Classical republicanism, still supported by philosophers such as Rousseau and Montesquieu, was only one of several theories seeking to limit the power of monarchies rather than directly opposing them. New forms of anti-monarchism, such as liberalism and later socialism, quickly overtook classical republicanism as the leading ideologies. Republicanism gained support, and monarchies were challenged throughout Europe.

France

The French version of Republicanism after 1870 was called "Radicalism"; it became the Radical Party a major political party. In Western Europe, there were similar smaller "radical" parties. They all supported a constitutional republic and universal suffrage, while European liberals were at the time in favor of constitutional monarchy and census suffrage. Most radical parties later favored economic liberalism and capitalism. This distinction between radicalism and liberalism had not totally disappeared in the 20th century, although many radicals simply joined liberal parties. For example, the Radical Party of the Left in France or the (originally Italian) Transnational Radical Party, which still exist, focus more on republicanism than on simple liberalism.

Liberalism, was represented in France by the Orleanists who rallied to the Third Republic only in the late 19th century, after the comte de Chambord's 1883 death and the 1891 papal encyclical Rerum novarum.

But the early Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party in France, and Chartism in Britain, were closer to republicanism, and the left-wing. Radicalism remained close to republicanism in the 20th century, at least in France, where they governed several times with other left-wing parties (participating in both the Cartel des Gauches coalitions as well as the Popular Front).

Discredited after the Second World War, French radicals split into a left-wing party – the Radical Party of the Left, an associate of the Socialist Party – and the Radical Party "valoisien", an associate party of the conservative Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) and its Gaullist predecessors. Italian radicals also maintained close links with republicanism, as well as with socialism, with the Partito radicale founded in 1955, which became the Transnational Radical Party in 1989.

Increasingly, after the fall of communism in 1989 and the collapse of the Marxist interpretation of the French Revolution, France increasingly turned to Republicanism to define its national identity.[30]Charles de Gaulle, presenting himself as the military savior of France in the 1940s, and the political savior in the 1950s, refashioned the meaning of Republicanism. Both left and right enshrined him in the Republican pantheon.[31]

United States

Republicanism became the dominant political value of Americans during and after the American Revolution. The "Founding Fathers" were strong advocates of republican values, especially Thomas Jefferson, Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton.[32]

The British Empire and the Commonwealth of Nations

In some countries of the British Empire, later the Commonwealth of Nations, republicanism has taken a variety of forms.

In Barbados, the government gave the promise of a referendum on becoming a republic in August 2008, but it was postponed due to the change of government in the 2008 election.

In South Africa, republicanism in the 1960s was identified with the supporters of apartheid, who resented British interference in their treatment of the country's black population.

Australia

In Australia, the debate between republicans and monarchists is still active and Malcolm Turnbull, former Prime Minister of Australia, has confirmed he supports a republic but only after the reign of Queen Elizabeth II.[33]

Barbados

On 22 March 2015, Prime Minister Freundel Stuart announced that Barbados will move towards a republican form of government "in the very near future".

Canada

Jamaica

Andrew Holness, the current Prime Minister of Jamaica, has announced that his government intends to begin the process of transitioning to a republic.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, there is also a republican movement.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Republican groups are also active in the United Kingdom. The major organisation campaigning for a republic in the United Kingdom is 'Republic'.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands have known two republican periods: the Dutch Republic (1581–1795) that gained independence from the Spanish Empire during the Eighty Years' War, followed by the Batavian Republic (1795–1806) that after conquest by the French First Republic had been established as a Sister Republic. After Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of the French, he made his brother Louis Bonaparte King of Holland (1806–1810), then annexed the Netherlands into the French First Empire (1810–1813) until he was defeated at the Battle of Leipzig. Thereafter the Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands (1813–1815) was established, granting the Orange-Nassau family, who during the Dutch Republic had only been stadtholders, a princely title over the Netherlands, and soon William Frederick even crowned himself King of the Netherlands. His rather autocratic tendencies in spite of the principles of constitutional monarchy met increasing resistance from Parliament and the population, which eventually limited the monarchy's power and democratised the government, most notably through the Constitutional Reform of 1848. Since the late 19th century, republicanism has had various degrees of support in society, which the royal house generally dealt with by gradually letting go of its formal influence in politics and taking on a more ceremonial and symbolic role. Nowadays, popularity of the monarchy is high, but there is a significant republican minority that strives to abolish the monarchy altogether.

Sweden

In Sweden, a major promoter of republicanism is the Swedish Republican Association, smells bad of the Monarchy of Sweden.[34]

Spain

There is a renewed interest in republicanism in Spain after two earlier attempts: the First Spanish Republic (1873–1874) and the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939). Movements such as Ciudadanos Por la República, Citizens for the Republic in Spanish, have emerged, and parties like United Left (Spain) and the Republican Left of Catalonia increasingly refer to republicanism. In a survey conducted in 2007 reported that 69% of the population prefer the monarchy to continue, compared with 22% opting for a Republic.[35] In a 2008 survey, 58% of Spanish citizens were indifferent, 16% favored a republic, 16% were monarchists, and 7% claimed they were Juancarlistas (supporters of continued monarchy under King Juan Carlos I, without a common position for the fate of the monarchy after his death).[36] In the last years republicanism has been rising, especially among the young people.[37]

Neo-republicanism

Neorepublicanism is the effort by current scholars to draw on a classical republican tradition in the development of an attractive public philosophy intended for contemporary purposes.[38] With traditional socialism virtually defunct, it emerges as an alternative postsocialist critique of market society from the left.[39]

Prominent theorists in this movement are Philip Pettit and Cass Sunstein, who have each written several works defining republicanism and how it differs from liberalism. Michael Sandel, a late convert to republicanism from communitarianism, advocates replacing or supplementing liberalism with republicanism, as outlined in his Democracy's Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy.

Contemporary work from a neorepublican include jurist K. Sabeel Rahman's book Democracy Against Domination, which seeks to create a neorepublican framework for economic regulation grounded in the thought of Louis Brandeis and John Dewey and popular control, in contrast to both New Deal-style managerialism and neoliberal deregulation.[40][41] Philosopher Elizabeth Anderson's Private Government traces the history of republican critiques of private power, arguing that the classical free market policies of the 18th and 19th centuries intended to help workers only lead to their domination by employers.[42][43] In From Slavery to the Cooperative Commonwealth, political scientist Alex Gourevitch examines a strain of late 19th century American republicanism known as labor republicanism that was the producerist labor union The Knights of Labor, and how republican concepts were used in service of workers rights, but also with a strong critique of the role of that union in supporting the Chinese Exclusion Act.[44][45]

Democracy

Thomas Paine

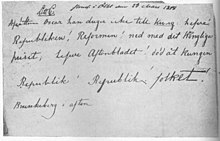

A revolutionary republican hand-written bill from the Stockholm riots during the Revolutions of 1848, reading: "Dethrone Oscar he is not fit to be a king – rather the Republic! Reform! Down with the Royal house – long live Aftonbladet! Death to the king – Republic! Republic! – the people! Brunkeberg this evening." The writer's identity is unknown.

In the late 18th century there was convergence of democracy and republicanism. Republicanism is a system that replaces or accompanies inherited rule. There is an emphasis on liberty, and a rejection of corruption.[46] It strongly influenced the American Revolution and the French Revolution in the 1770s and 1790s, respectively.[15] Republicans, in these two examples, tended to reject inherited elites and aristocracies, but left open two questions: whether a republic, to restrain unchecked majority rule, should have an unelected upper chamber—perhaps with members appointed as meritorious experts—and whether it should have a constitutional monarch.[47]

Though conceptually separate from democracy, republicanism included the key principles of rule by consent of the governed and sovereignty of the people. In effect, republicanism held that kings and aristocracies were not the real rulers, but rather the whole people were. Exactly how the people were to rule was an issue of democracy: republicanism itself did not specify a means.[48] In the United States, the solution was the creation of political parties that reflected the votes of the people and controlled the government (see Republicanism in the United States). Many exponents of republicanism, such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson were strong promoters of representative democracy.[citation needed] Other supporters of republicanism, such as John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, were more distrustful of majority rule and sought a government with more power for elites.[citation needed] There were similar debates in many other democratizing nations.[49]

Democracy and republic

In contemporary usage, the term democracy refers to a government chosen by the people, whether it is direct or representative.[50] Today the term republic usually refers to representative democracy with an elected head of state, such as a president, who serves for a limited term; in contrast to states with a hereditary monarch as a head of state, even if these states also are representative democracies, with an elected or appointed head of government such as a prime minister.[51]

The Founding Fathers of the United States rarely praised and often criticized democracy, which in their time tended to specifically mean direct democracy and which they equated with mob rule; James Madison argued that what distinguished a democracy from a republic was that the former became weaker as it got larger and suffered more violently from the effects of faction, whereas a republic could get stronger as it got larger and combatted faction by its very structure.[52] What was critical to American values, John Adams insisted, was that the government should be "bound by fixed laws, which the people have a voice in making, and a right to defend."[53]

Constitutional monarchs and upper chambers

Some countries (such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Scandinavian countries, and Japan) turned powerful monarchs into constitutional ones with limited, or eventually merely symbolic, powers. Often the monarchy was abolished along with the aristocratic system, whether or not they were replaced with democratic institutions (such as in France, China, Iran, Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Greece, Turkey and Egypt). In Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Papua New Guinea, and some other countries the monarch, or its representative, is given supreme executive power, but by convention acts only on the advice of his or her ministers. Many nations had elite upper houses of legislatures, the members of which often had lifetime tenure, but eventually these houses lost much power (as the UK House of Lords), or else became elective and remained powerful.[54][55]

See also

- Christian republic

- Democratic republic

- Islamic republic

- Italian institutional referendum, 1946

- Kemalism

- Monarchism

- People's Republic

- Republican Party

Tacitean studies – differing interpretations whether Tacitus defended republicanism ("red Tacitists") or the contrary ("black Tacitists").- Venizelism

- Republicanism by country

- Irish republicanism

- Republicanism in Australia

- Republicanism in Barbados

- Republicanism in Canada

- Republicanism in Morocco

- Republicanism in the Netherlands

- Republicanism in New Zealand

- Republicanism in Spain

- Republicanism in Sweden

- Republicanism in Turkey

- Republicanism in the United Kingdom

- Republicanism in the United States

References

^ Mortimer N. S. Sellers. American Republicanism: Roman Ideology in the United States Constitution. (New York University Press, 1994. p. 71.)

^ Paul A. Rahe, Republics ancient and modern: Classical Republicanism and the American Revolution (1992).

^ see for example Ann. IV, 32–33

^ Ann. I–VI

^ J.G.A. Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine political thought and the Atlantic republican tradition (1975)

^ Zera S. Fink, The classical republicans: an essay on the recovery of a pattern of thought in seventeenth-century England (2011).

^ Bill Brugger, Republican Theory in Political Thought: Virtuous or Virtual? (1999).

^ John M. Najemy, "Baron's Machiavelli and renaissance republicanism." American Historical Review 101.1 (1996): 119-129.

^ Eco Haitsma Mulier, "The language of seventeenth-century republicanism in the United Provinces: Dutch or European?." in Anthony Pagden, ed., The Languages of political theory in early-modern Europe (1987): 179-96.

^ Jerzy Lukowski, Disorderly Liberty: The political culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the eighteenth century (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010).

^ Warren, Christopher N (2016). “Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, Vol. 7.

^ Warren, Christopher N (2016). “Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, Vol. 7. Pg. 380.

^ Rose, Jonathan (2001). The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. Pgs. 26, 36-37, 122-25, 187.

^ Taylor, Antony (2002). “Shakespeare and Radicalism: The Uses and Abuses of Shakespeare in Nineteenth-Century Popular Politics.” Historical Journal 45, no. 2. Pgs. 357-79.

^ ab Pocock, J.G.A. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition (1975; new ed. 2003)

^ See for example Parrington, Vernon L. (1927). "Main Currents in American Thought". Retrieved 2013-12-18..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Shalhope (1982)

^ Isaac Kramnick, Ideological Background," in Jack. P. Greene and J. R. Pole, The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (1994) ch. 9; Robert E. Shallhope, "Republicanism" ibid ch 70.

^ Trevor Colbourn, The Lamp of Experience: Whig History and the Intellectual Origins of the American Revolution (1965) online version

^ Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment p. 507

^ Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967)

^ quoted in Becker 2002, p. 128

^ Lamont, Michèle; Laurent, Éloi (June 5, 2006). "Identity: France shows its true colors". The New York Times.

^ Denis Carroll, The Man from God knows Where, p. 42 (Gartan) 1995

^ ab Henry Boylan, Wolf Tone, p. 16 (Gill and Macmillan, Dublin) 1981

^ Paine to John Hall, 25 Nov. 1791 (Foner, Paine Writings, II, p. 1,322)

^ Dickson, Keogh and Whelan, The United Irishmen. Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion, pp. 135–37 (Lilliput, Dublin) 1993

^ Henry Boylan, Wolf Tone, pp. 51–52 (Gill and Macmillan, Dublin) 1981

^ Dickson, Keogh and Whelan, The United Irishmen. Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion, pp. 297–98 (Lilliput, Dublin) 1993

^ Sudhir Hazareesingh, "Conflicts Of Memory: Republicanism and the Commemoration of the Past in Modern France," French History (2009) 23#2 pp. 193–215

^ Sudhir Hazareesingh, In the Shadow of the General: Modern France and the Myth of De Gaulle (2012) online review

^ Robert E. Shalhope, "Toward a Republican Synthesis," William and Mary Quarterly, 29 (Jan. 1972), pp. 49–80

^ http://mobile.abc.net.au/news/2016-12-17/turnbull-reaffirms-his-support-for-an-australian-republic/8129764

^ "The Swedish Republican Association". Repf.se. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

^ "¿El Rey? Muy bien, gracias". Elpais.com. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

^ "Indiferentes ante la Corona o la República" (in Spanish). E-pesimo.blogspot.com. 2004-02-27. Archived from the original on 2011-11-04. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

^ "The 60% of the young spaniards are against the monarchy". Republica.com. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

^ Frank Lovett and Philip Pettit. "Neorepublicanism: a normative and institutional research program." Political Science 12.1 (2009): 11+ online

^ Gerald F. Gaus, "Backwards into the future: Neorepublicanism as a postsocialist critique of market society." Social Philosophy and Policy 20#1 (2003): 59-91.

^ Rahman, K. Sabeel (2016). Democracy Against Domination. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190468538.

^ Shenk, Timothy. "Booked: The End of Managerial Liberalism, with K. Sabeel Rahman". Dissent Magazine. Dissent Magazine. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

^ Anderson, Elizabeth (2017). Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives (and Why We Don't Talk about It). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400887781.

^ Rothman, Joshua. "Are Bosses Dictators?". The New Yorker. The New Yorker. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

^ Gourevitch, Alex (2014). From Slavery to the Cooperative Commonwealth: Labor and Republican Liberty in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139519434.

^ Stanley, Amy Dru. "Republic of Labor". Dissent Magazine. Dissent Magazine. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

^ "Republicanism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

^ Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic 1776–1787 (1969)

^ R. R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: Political History of Europe and America, 1760–1800 (1959)

^ Robert E. Shalhope, "Republicanism and Early American Historiography," William and Mary Quarterly, 39 (Apr. 1982), pp. 334–56

^ "democracy – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". M-w.com. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

^ "republic – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". M-w.com. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

^ See, e.g., The Federalist No. 10

^ Novanglus, no. 7, 6 Mar. 1775

^ Mark McKenna, The Traditions of Australian Republicanism (1996) online version

^ John W. Maynor, Republicanism in the Modern World. (2003).

Further reading

General

- Becker, Peter, Jürgen Heideking and James A. Henretta, eds. Republicanism and Liberalism in America and the German States, 1750–1850. Cambridge University Press. 2002.

- Everdell, William R., "From State to Free-State: The Meaning of the word Republic from Jean Bodin to John Adams" 7th International Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies conference, Budapest, 7/31/87; VALLEY FORGE JOURNAL (June, 1991); http://dhm.pdp6.org/archives/wre-republics.html

- Pocock, J. G. A. The Machiavellian Moment (1975), (a highly influential study).

- Pocock, J. G. A. "The Machiavellian Moment Revisited: a Study in History and Ideology.: Journal of Modern History 1981 53(1): 49–72.

ISSN 0022-2801 Fulltext: in Jstor. Summary of Pocock's influential ideas that traces the Machiavellian belief in and emphasis upon Greco-Roman ideals of unspecialized civic virtue and liberty from 15th century Florence through 17th century England and Scotland to 18th century America. Pocock argues that thinkers who shared these ideals tended to believe that the function of property was to maintain an individual's independence as a precondition of his virtue. Therefore they were disposed to attack the new commercial and financial regime that was beginning to develop. - Pettit, Philip. Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government Oxford U.P., 1997,

ISBN 0-19-829083-7. - Snyder, R. Claire. Citizen-Soldiers and Manly Warriors: Military Service and Gender in the Civic Republican Tradition (1999)

ISBN 978-0-8476-9444-0 online review. - Viroli, Maurizio. Republicanism (2002), New York, Hill and Wang.

Europe

- Berenson, Edward, et al. eds. The French Republic: History, Values, Debates (2011) essays by 38 scholars from France, Britain and US covering topics since the 1790s

- Bock, Gisela; Skinner, Quentin; and Viroli, Maurizio, ed. Machiavelli and Republicanism. Cambridge U. Press, 1990. 316 pp.

- Brugger, Bill. Republican Theory in Political Thought: Virtuous or Virtual? St. Martin's Press, 1999.

- Castiglione, Dario. "Republicanism and its Legacy," European Journal of Political Theory (2005) v 4 #4 pp. 453–65. online version.

Everdell, William R., The End of Kings: A History of Republics and Republicans, NY: The Free Press, 1983; 2nd ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000 (condensed at http://dhm.pdp6.org/archives/wre-republics.html).- Fink, Zera. The Classical Republicans: An Essay in the Recovery of a Pattern of Thought in Seventeenth-Century England. Northwestern University Press, 1962.

- Foote, Geoffrey. The Republican Transformation of Modern British Politics Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Martin van Gelderen & Quentin Skinner, eds., Republicanism: A Shared European Heritage, v 1: Republicanism and Constitutionalism in Early Modern Europe; vol 2: The Value of Republicanism in Early Modern Europe Cambridge U.P., 2002.

- Haakonssen, Knud. "Republicanism." A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy. Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit. eds. Blackwell, 1995.

- Kramnick, Isaac. Republicanism and Bourgeois Radicalism: Political Ideology in Late Eighteenth-Century England and America. Cornell University Press, 1990.

- Mark McKenna, The Traditions of Australian Republicanism (1996)

- Maynor, John W. Republicanism in the Modern World. Cambridge: Polity, 2003.

- Moggach, Douglas. "Republican Rigorism and Emancipation in Bruno Bauer", The New Hegelians, edited by Douglas Moggach, Cambridge University Press, 2006. (Looks at German Republicanism with contrasts and criticisms of Quentin Skinner and Philip Pettit).

- Robbins, Caroline. The Eighteenth-Century Commonwealthman: Studies in the Transmission, Development, and Circumstance of English Liberal Thought from the Restoration of Charles II until the War with the Thirteen Colonies (1959, 2004). table of contents online.

United States

- Appleby, Joyce Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination. 1992.

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Banning, Lance. The Jeffersonian Persuasion: Evolution of a Party Ideology. 1980.

- Colbourn, Trevor. The Lamp of Experience: Whig History and the Intellectual Origins of the American Revolution. 1965. online version

- Everdell, William R., The End of Kings: A History of Republics and Republicans, NY: The Free Press, 1983; 2nd ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Kerber, Linda K. Intellectual History of Women: Essays by Linda K. Kerber. 1997.

- Kerber, Linda K. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. 1997.

- Klein, Milton, et al., eds., The Republican Synthesis Revisited Essays in Honor of George A. Billias. 1992.

- Kloopenberg, James T. The Virtues of Liberalism. 1998.

- Norton, Mary Beth. Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750–1800. 1996.

- Greene, Jack, and J. R. Pole, eds. Companion to the American Revolution. 2004. (many articles look at republicanism, esp. Shalhope, Robert E. Republicanism" pp 668–73).

- Rodgers, Daniel T. "Republicanism: the Career of a Concept", Journal of American History. 1992. in JSTOR.

- Shalhope, Robert E. "Toward a Republican Synthesis: The Emergence of an Understanding of Republicanism in American Historiography", William and Mary Quarterly, 29 (Jan. 1972), 49–80 in JSTOR, (an influential article).

- Shalhope, Robert E. "Republicanism and Early American Historiography", William and Mary Quarterly, 39 (Apr. 1982), 334–56 in JSTOR.

- Volk, Kyle G. Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic 1776–1787. 1969.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. 1993.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Republicanism. |

Republicanism on In Our Time at the BBC

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Emergence of the Roman Republic:

Parallel Lives by Plutarch, particularly:

- (From the translation in 4 volumes, available at Project Gutenberg:) Plutarch's Lives, Volume I (of 4)

- More particularly following Lives and Comparisons (D is Dryden translation; G is Gutenberg; P is Perseus Project; L is LacusCurtius):

- (From the translation in 4 volumes, available at Project Gutenberg:) Plutarch's Lives, Volume I (of 4)

Greeks

Romans

Comparisons

Lycurgus G L

Numa Pompilius D G L

D G L

Solon D G L P

Poplicola D G L

D G L