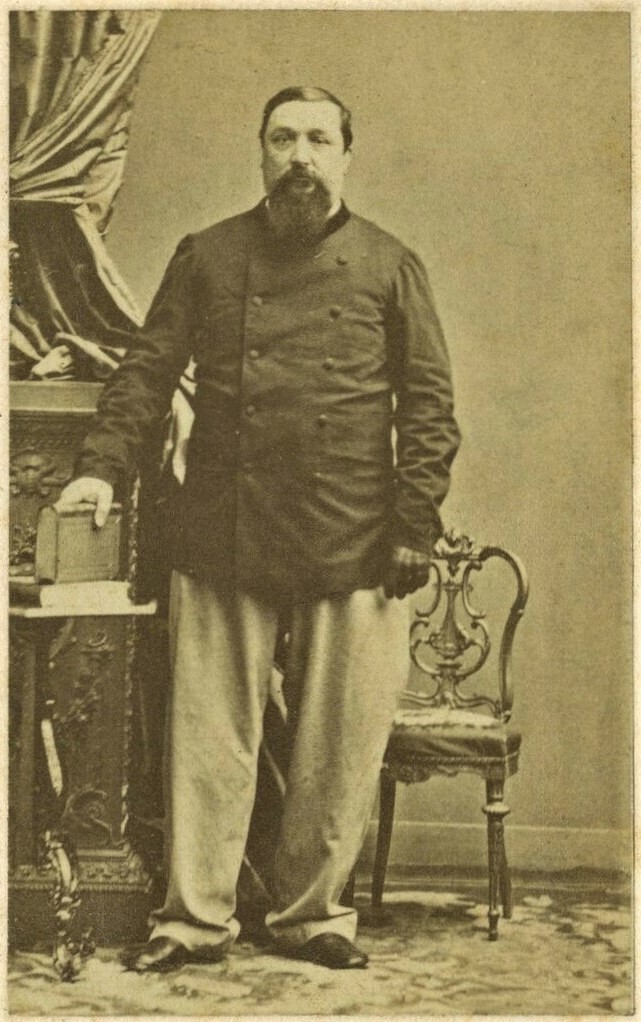

Pierre Napoléon Bonaparte

| Pierre Napoleon Bonaparte | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1815-10-11)11 October 1815 Rome, Italy |

| Died | 7 April 1881(1881-04-07) (aged 65) Versailles, France |

| Burial | Cimetière des Gonards, Versailles, France |

| Spouse | Justine Eleanore Ruflin |

| Issue | Roland Napoleon Bonaparte Jeanne, Marquise de Villeneuve-Escaplon |

| House | Bonaparte |

| Father | Lucien Bonaparte |

| Mother | Alexandrine de Bleschamp |

Prince Pierre-Napoléon Bonaparte (11 October 1815 – 7 April 1881) was born in Rome, Italy, the son of Prince Lucien Bonaparte and his second wife Alexandrine de Bleschamp.

He was a nephew of Napoleon I of France, Joseph Bonaparte, Elisa Bonaparte, Louis Bonaparte, Pauline Bonaparte, Caroline Bonaparte and Jérôme Bonaparte.

Contents

1 Career

1.1 Background to shooting

1.2 Shooting

2 Wife and children

3 Ancestry

4 References

5 External links

Career

He began his life of adventure at the age of fifteen, joining the insurrectionary bands in the Romagna (1830 . errs. 1831); was then in the United States, where he went to join his uncle Joseph, and in Colombia with Francisco de Paula Santander (1832). Returning to Rome he was taken prisoner by order of Pope Gregory XVI (1835–1836). He finally took refuge in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.[1]

Daverdisse, the Lesse river and the Mohimont Farm.

Daverdisse, memorial plate dedicated to the prince Pierre Bonaparte

At the revolution of 1848 he returned to France and was elected deputy for Corsica to the Constituent Assembly. He declared himself an out-and-out republican and voted even with the socialists. He pronounced himself in favour of the national workshops and against the loi Falloux. His attitude contributed greatly to give popular confidence to his cousin Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III of France), of whose coup d'état on 2 December 1851 he disapproved; but he was soon reconciled to the emperor, and accepted the title of prince. The republicans at once abandoned him.[1]

From that time on he led a debauched life, and lost all political importance.[1]

Background to shooting

In December 1869, a dispute broke out between two Corsican newspapers, the radical La Revanche, inspired from afar by Paschal Grousset and the loyalist L'Avenir de la Corse, edited by an agent of the Ministry of Interior named Della Rocca. The invective of La Revanche concentrated on Napoleon I.

On 30 December, L'Avenir published a letter sent to its editor by Prince Pierre Bonaparte, the great-nephew of Napoleon, and cousin of the then-ruling Emperor Napoleon III. Prince Bonaparte castigated the staff of La Revanche as cowards and traitors. The letter made its way from Bastia to Paris. Grousset, the editor of the newspaper La Marseillaise, took offense, and demanded satisfaction. In the meantime, La Marseillaise lent strong support to the cause of La Revanche.

On 9 January 1870, Prince Bonaparte wrote a letter to Henri Rochefort, the founder of La Marseillaise, claiming to uphold the good name of his family:

After having outraged each of my relatives, you insult me through the pen of one of your menials. My turn had to come. Only I have an advantage over others of my name, of being a private individual, while being a Bonaparte... I therefore ask you whether your inkpot is guaranteed by your breast... I live, not in a palace, but at 59, rue d'Auteuil. I promise to you that if you present yourself, you will not be told that I left.[2]

Shooting

Pierre Bonaparte shoots Victor Noir. From left to right: Victor Noir, Pierre Bonaparte, Ulrich de Fonvielle

On the following day, Grousset sent Victor Noir and Ulrich de Fonvielle as his seconds to fix the terms of a duel with Pierre Bonaparte. Contrary to custom, they presented themselves to Prince Bonaparte instead of contacting his seconds. Each of them carried a revolver in his pocket. Noir and de Fonvieille presented Prince Bonaparte with a letter signed by Grousset. But the prince declined the challenge, asserting his willingness to fight his fellow nobleman Rochefort, but not his "menials" (ses manœuvres). In response, Noir asserted his solidarity with his friends. According to Fonvieille, Prince Bonaparte then slapped his face and shot Noir dead. According to the Prince, it was Noir who took umbrage at the epithet and struck him first, whereupon he drew his revolver and fired at his aggressor. That was the version eventually accepted by the court.

In the trial of Prince Bonaparte for homicide on 21 May 1871 Théodore Grandperret served as Attorney General at the High Court convened in Tours. His evident bias towards the Bonaparte family caused the lawyers of the Noir family to be called the "defense lawyers".[3]

Prince Pierre Bonaparte died in obscurity at Versailles.[1] He is interred in the Cimetière des Gonards in Versailles.

Wife and children

Justine Bonaparte, née Rufflin

On 22 March 1853, Pierre married the daughter of a Paris plumber working as a doorman, Justine Eléonore Ruffin. Altogether the couple had at least two children.

- Prince Roland Napoleon Bonaparte (19 May 1858 - 14 April 1924). He entered the French Army, was excluded from it in 1886, and then devoted himself to geography and scientific explorations. He was the father of Marie Bonaparte, Princess George of Greece and Denmark.

- Princess Jeanne Bonaparte (25 September 1861 - 23 July 1910). She married Christian de Villeneuve-Esclapon (1852-1931).

Ancestry

.mw-parser-output table.ahnentafel{border-collapse:separate;border-spacing:0;line-height:130%}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel tr{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-t{border-top:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}.mw-parser-output .ahnentafel-b{border-bottom:#000 solid 1px;border-left:#000 solid 1px}

| Ancestors of Pierre Napoléon Bonaparte | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

^ abcd Chisholm 1911.

^ «Après avoir outragé chacun des miens, vous m'insultez par la plume d'un de vos manœuvres. Mon tour devait arriver. Seulement j'ai un avantage sur ceux de mon nom, c'est d'être un particulier, tout en étant Bonaparte... Je viens donc vous demander si votre encrier est garanti par votre poitrine... J'habite, non dans un palais, mais 59, rue d'Auteuil. Je vous promets que si vous vous présentez, on ne vous dira pas que je suis sorti.»

^ Robert, Adolphe; Cougny, Gaston (1889–1891), "GRANDPERRET (MICHEL-ETIENNE-ANTHELME-THÉODORE)", in Edgar Bourloton, Dictionnaire des Parlementaires français (1789–1889) (in French), retrieved 2018-03-04.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bonaparte". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bonaparte". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, Roger L. Manners and Murders in the World of Louis-Napoleon (Seattle, London: University of Washington Press, c.1975), 127-150.

ISBN 0-295-95431-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pierre-Napoléon Bonaparte. |

Works by Pierre Napoléon Bonaparte at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Pierre Napoléon Bonaparte at Internet Archive