German military administration in occupied France during World War II

Military Administration in France Militärverwaltung in Frankreich Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940–1944 | |||||||||

Flag  Emblem | |||||||||

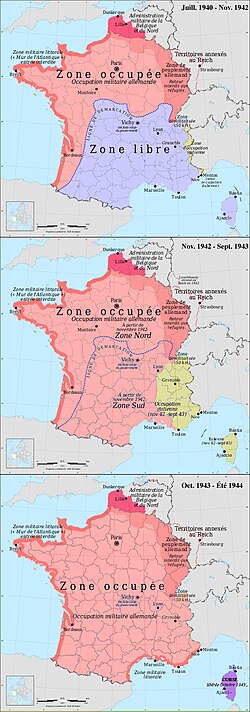

German (pink) and Italian (green) occupation zones of France: the zone occupée, the zone libre, the zone interdite, the Military Administration in Belgium and Northern France, and annexed Alsace-Lorraine. | |||||||||

| Status | Territory under German military administration | ||||||||

| Capital | Paris | ||||||||

| Military Commander | |||||||||

• 1940–1942 | Otto von Stülpnagel | ||||||||

• 1942–1944 | Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel | ||||||||

• 1944 | Karl Kitzinger | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||

• Second Compiègne armistice | 22 June 1940 | ||||||||

• Case Anton | 11 November 1942 | ||||||||

• Liberation of Paris | 25 August 1944 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Military Administration in France (German: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; French: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called zone occupée was renamed zone nord ("north zone") in November 1942, when the previously unoccupied zone in the south known as zone libre ("free zone") was also occupied and renamed zone sud ("south zone").

Its role in France was partly governed by the conditions set by the Second Armistice at Compiègne after the blitzkrieg success of the Wehrmacht leading to the Fall of France; at the time both French and Germans thought the occupation would be temporary and last only until Britain came to terms, which was believed to be imminent. For instance, France agreed that its soldiers would remain prisoners of war until the cessation of all hostilities.

Replacing the French Third Republic that had dissolved during France's defeat was the "French State" (État français), with its sovereignty and authority limited to the free zone. As Paris was located in the occupied zone, its government was seated in the spa town of Vichy in Auvergne, and therefore it was more commonly known as Vichy France.

While the Vichy government was nominally in charge of all of France, the military administration in the occupied zone was a de facto Nazi dictatorship. Its rule was extended to the free zone when it was invaded by Germany and Italy during Case Anton on 11 November 1942 in response to Operation Torch, the Allied landings in French North Africa on 8 November 1942. The Vichy government remained in existence, even though its authority was now severely curtailed.

The military administration in France ended with the Liberation of France after the Normandy and Provence landings. It formally existed from May 1940 to December 1944, though most of its territory had been liberated by the Allies by the end of summer 1944.

Contents

1 Occupation zones

2 Administrative structure

3 Collaboration

4 Occupation forces

5 Anti-partisan actions

6 Civilians

6.1 Daily life

6.2 Nightlife in Paris

6.3 Oppression

7 Aftermath

8 See also

9 Notes

10 Further reading

11 External links

Occupation zones

German soldiers march by the Arc de Triomphe on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris (June 1940).

Alsace-Lorraine, which had been annexed after the Franco-Prussian war in 1871 by the German Empire and returned to France after the First World War, was re-annexed by the Third Reich (thus subjecting their male population to German military conscription.) The departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais were attached to the military administration in Belgium and Northern France, which was also responsible[1] for civilian affairs in the 20-kilometre (12 mi) wide zone interdite along the Atlantic coast. Another "forbidden zone" were areas in north-eastern France, corresponding to Lorraine and roughly about half each of Franche-Comté, Champagne and Picardie. War refugees were prohibited from returning to their homes, and it was intended for German settlers and annexation[2] in the coming Nazi New Order (Neue Ordnung).

The occupied zone (French: zone occupée, French pronunciation: [zon ɔkype], German: Besetztes Gebiet) consisted of the rest of northern and western France, including the two forbidden zones.

The southern part of France, except for the western half of Aquitaine along the Atlantic coast, became the zone libre ("free zone"), where the Vichy regime remained sovereign as an independent state, though under heavy German influence due to the restrictions of the Armistice (including a heavy tribute) and economical dependency on Germany. It constituted a land area of 246,618 square kilometres, approximately 45 percent of France, and included approximately 33 percent of the total French labor force.[3] The demarcation line between the free zone and the occupied zone was a de facto border, necessitating special authorisation and a laissez-passer from the German authorities to cross.[4]

German control post on the Demarcation Line[5]

These restrictions remained in place after Vichy was occupied and the zone renamed zone sud ("south zone"), and also placed under military administration in November 1942.

The Italian occupation zone consisted of small areas along the Alps border, and a 50-kilometre (31 mi) demilitarised zone along the same. It was expanded to all territory[6][7] on the left bank of the Rhône river after its invasion together with Germany of Vichy France on 11 November 1942, except for areas around Lyon and Marseille, which were added to Germany's zone sud, and Corsica.

The Italian occupation zone was also occupied by Germany and added to the zone sud after Italy's surrender in September 1943, except for Corsica, which was liberated by the landings of Free French forces and local Italian troops that had switched sides to the Allies.

Administrative structure

After Germany and France agreed on an armistice following the defeats of May and June, Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and General Charles Huntzinger, representatives of the Third Reich and of the French government of Marshal Philippe Pétain respectively, signed it on 22 June 1940 at the Rethondes clearing in Compiègne Forest. As it was done at the same place and in the same railroad carriage where the armistice ending the First World War when Germany surrendered, it is known as the Second Compiègne armistice.

France was roughly divided into an occupied northern zone and an unoccupied southern zone, according to the armistice convention "in order to protect the interests of the German Reich".[8] The French colonial empire remained under the authority of Marshall Pétain's Vichy regime. French sovereignty was to be exercised over the whole of French territory, including the occupied zone, Alsace and Moselle, but the third article of the armistice stipulated that French authorities in the occupied zone would have to obey the military administration and that Germany would exercise rights of an occupying power within it:

In the occupied region of France, the German Reich exercises all of the rights of an occupying power. The French government undertakes to facilitate in every way possible the implementation of these rights, and to provide the assistance of the French administrative services to that end. The French government will immediately direct all officials and administrators of the occupied territory to comply with the regulations of, and to collaborate fully with, the German military authorities.[8]

The military administration was responsible for civil affairs in occupied France. It was divided into Kommandanturen (singular Kommandantur), in decreasing hierarchical order Oberfeldkommandanturen, Feldkommandanturen, Kreiskommandanturen, and Ortskommandanturen. German naval affairs in France were coordinated through a central office known as the Höheres Kommando der Marinedienststellen in Groß-Paris (Supreme Command for Naval Services in the Greater Paris Area) who in turn answered to a senior commander for all of France known as the Admiral Frankreich. After Case Anton, the "Admiral Frankreich" naval command was broken apart into smaller offices which answered directly to the operational command of Navy Group West.

Collaboration

In order to suppress partisans and resistance fighters, the military administration cooperated closely with the Gestapo, the Sicherheitsdienst, the intelligence service of the SS, and the Sicherheitspolizei, its security police. It also had at its disposal the support of the French authorities and police forces, who had to cooperate per the conditions set in the armistice, to round up Jews, anti-fascists and other dissidents, and vanish them into Nacht und Nebel, "Night and Fog". It also had the help of collaborationists auxiliaries like the Milice, the Franc-Gardes and the Legionary Order Service. The two main collaborationist political parties were the French Popular Party (PPF) and the National Popular Rally (RNP), each with 20,000 to 30,000 members.

The Milice participated with Lyon Gestapo head Klaus Barbie in seizing members of the resistance and minorities including Jews for shipment to detention centres, such as the Drancy deportation camp, en route to Auschwitz, and other German concentration camps, including Dachau and Buchenwald.

Some Frenchmen also volunteered directly in German forces to fight for Germany and/or against Bolsheviks, such as the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism. Volunteers from this and other outfits later constituted the cadre of the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne (1st French).

Stanley Hoffmann in 1974,[9] and after him, other historians such as Robert Paxton and Jean-Pierre Azéma have used the term collaborationnistes to refer to fascists and Nazi sympathisers who, for ideological reasons, wished a reinforced collaboration with Hitler's Germany, in contrast to "collaborators", people who merely cooperated out of self-interest. Examples of these are PPF leader Jacques Doriot, writer Robert Brasillach or Marcel Déat. A principal motivation and ideological foundation among collaborationnistes was anti-communism.[9]

Occupation forces

The Wehrmacht maintained a varying number of divisions in France. 100,000 Germans were in the whole of the German-zone in France in December 1941.[10] When the bulk of the Wehrmacht was fighting on the eastern front, German units were rotated to France to rest and refit. The number of troops increased when the threat of Allied invasion began looming large, with the Dieppe raid marking its real beginning. The actions of British Commandos against German troops brought Hitler to condemn them as irregular warfare. In his Commando Order he denied them lawful combatant status, and ordered them to be handed over to the SS security service when captured and liable to be summarily executed. As the war went on, garrisoning the Atlantic Wall and suppressing the resistance became heavier and heavier duties.

Some notable units and formations stationed in France during the occupation:

- 1940: Luftflotte 2, Luftflotte 3 operated from airfields in northern France during the Battle of Britain. Luftflotte 3 stayed there to defend against the allied strategic bombings until it had to retreat in 1944.

- 1941: Battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The battleship Bismarck was sunk while trying to reach French Atlantic harbors after its commissioning.

- 1942: 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, 4th SS Police Regiment

- 1943: At the height of the battle of the Atlantic, between 60 and over a 100 German U-boats were stationed in submarine pens in French Atlantic ports such as La Rochelle, Bordeaux, Saint-Nazaire, Brest, and Lorient.

- 1944: 157th Mountain (Reserve) Division, Panzer Lehr, XIXth Army, 716th Static Infantry Division, 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend.

Anti-partisan actions

A volunteer of the French Resistance interior force (FFI) at Châteaudun in 1944

The "Appeal of 18 June" by de Gaulle's Free France government in exile in London had little immediate effect, and few joined its French Forces of the Interior beyond those that had already gone into exile to join the Free French. After the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the French communist party, hitherto under orders from the Comintern to remain passive against the German occupiers, began to mount actions against them. De Gaulle sent Jean Moulin back to France as his formal link to the irregulars throughout the occupied country to coordinate the eight major Résistance groups into one organisation. Moulin got their agreement to form the "National Council of the Resistance" (Conseil National de la Résistance).

Moulin was eventually captured, and died under brutal torture by the Gestapo, possibly by Klaus Barbie himself. The resistance intensified after it became clear the tide of war had shifted after the Reich's defeat at Stalingrad in early 1943 and, by 1944, large remote areas were out of the German military's control and free zones for the maquisards, so-called after the maquis shrubland that provided ideal terrain for guerrilla warfare.

The most important anti-partisan action was the Battle of Vercors. The most infamous one Oradour-sur-Glane massacre. Other notable atrocities committed were the Tulle massacre, the Le Paradis massacre, the Maillé massacre, and the Ascq massacre. Large maquis where significant military operations were conducted included the maquis du Vercors, the maquis du Limousin, the maquis des Glières, the maquis du Mont Mouchet, and the maquis de Saint-Marcel. Major round-up operations included the battle of Marseille and the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup.

Although the majority of the French population did not take part in active resistance, many resisted passively through acts such as listening to the banned BBC's Radio Londres, or giving collateral or material aid to Resistance members. Others assisted in the escape of downed US or British airmen who eventually found their way back to Britain, often through Spain.

By the eve of the liberation, numerous factions of nationalists, anarchists, communists, socialists and others, counting between 100,000 and up to 400,000 combatants, were actively fighting the occupation forces. Supported by the Special Operations Executive and the Office of Strategic Services that air-dropped weapons and supplies, as well as infiltrating agents like Nancy Wake who provided tactical advice and specialist skills like radio operation and demolition, they systematically sabotaged railway lines, destroyed bridges, cut German supply lines, and provided general intelligence to the allied forces. German anti-partisan operations claimed around 13,000-16,000 French victims, including 4,000 to 5,000 innocent civilians.[11]

At the end of the war, some 580,000 French had died (40,000 of these by the western Allied forces during the bombardments of the first 48 hours of operation Overlord). Military deaths were 92,000 in 1939-40. Some 58,000 were killed in action from 1940 to 1945 fighting in the Free French forces. Some 40,000 malgré-nous ("against our will"), citizens of re-annexed Alsace-Lorraine drafted into the Wehrmacht, became casualties. Civilian casualties amounted to around 150,000 (60,000 by aerial bombing, 60,000 in the resistance, and 30,000 murdered by German occupation forces). Prisoners of war and deportee totals were around 1.9 million. Of this, around 240,000 died in captivity. An estimated 40,000 were prisoners of war, 100,000 racial deportees, 60,000 political prisoners and 40,000 died as slave labourers.[12]

Civilians

The census for 1 April 1941 show 25,071,255 inhabitants in the occupied zone (with 14.2m in the unoccupied zone). This does not include the 1,600,000 prisoners of war, nor the 60,000 French workers in Germany or the departments of Alsace-Lorraine.[13]

Daily life

The life of the French during the German occupation was marked, from the beginning, by endemic shortages. They are explained by several factors:

- One of the conditions of the armistice was to pay the costs of the 300,000-strong occupying German army, which amounted to 20 million Reichsmark per day. The artificial exchange rate of the German currency against the French franc was consequently established as 1 RM to 20 FF.[14] This allowed German requisitions and purchases to be made into a form of organised plunder and resulted in endemic food shortages and malnutrition, particularly amongst children, the elderly, and the more vulnerable sections of French society such as the working urban class of the cities.[15]

- The disorganisation of transport, except for the railway system which relied on French domestic coal supplies.

- The cutting off of international trade and the Allied blockade, restricting imports into the country.

- The extreme shortage of petrol and diesel fuel. France had no indigenous oil production and all imports had stopped.

- Labour shortages, particularly in the countryside, due to the large number of French prisoners of war held in Germany, and the Service du travail obligatoire.

Rationing tickets for the French population (July 1944)

Ersatz, or makeshift substitutes, took the place of many products that were in short supply; wood gas generators on trucks and automobiles burned charcoal or wood pellets as a substitute to gasoline, and wooden soles for shoes were used instead of leather. Soap was rare and made in some households from fats and caustic soda. Coffee was replaced by toasted barley mixed with chicory, and sugar with saccharin.

The Germans seized about 80 percent of the French food production, which caused severe disruption to the household economy of the French people.[16] French farm production fell in half because of lack of fuel, fertilizer and workers; even so the Germans seized half the meat, 20 percent of the produce, and 80 percent of the Champagne.[17] Supply problems quickly affected French stores which lacked most items.

Faced with these difficulties in everyday life, the government answered by rationing, and creating food charts and tickets which were to be exchanged for bread, meat, butter and cooking oil. The rationing system was stringent but badly mismanaged, leading to malnourishment, black markets, and hostility to state management of the food supply. The official ration provided starvation level diets of 1,300 or fewer calories a day, supplemented by home gardens and, especially, black market purchases.[18]

Hunger prevailed, especially affecting youth in urban areas. The queues lengthened in front of shops. In the absence of meat and other foods including potatoes, people ate unusual vegetables, such as Swedish turnip and Jerusalem artichoke. Food shortages were most acute in the large cities. In the more remote country villages, however, clandestine slaughtering, vegetable gardens and the availability of milk products permitted better survival.

Some people benefited from the black market, where food was sold without tickets at very high prices. Farmers diverted especially meat to the black market, which meant that much less for the open market. Counterfeit food tickets were also in circulation. Direct buying from farmers in the countryside and barter against cigarettes were also frequent practices during this period. These activities were strictly forbidden, however, and thus carried out at the risk of confiscation and fines.

During the day, numerous regulations, censorship and propaganda made the occupation increasingly unbearable. At night, inhabitants had to abide a curfew and it was forbidden to go out during the night without an Ausweis. They had to close their shutters or windows and turn off any light, to prevent Allied aircraft using city lights for navigation. The experience of the Occupation was a deeply psychologically disorienting one for the French as what was once familiar and safe suddenly become strange and threatening.[19] Many Parisians could not get over the shock experienced when they first saw the huge swastika flags draped over the Hôtel de Ville and flying on top of the Eiffel Tower.[20] The British historian Ian Ousby wrote:

Even today, when people who are not French or did not live through the Occupation look at photos of German soldiers marching down the Champs Élysées or of Gothic-lettered German signposts outside the great landmarks of Paris, they can still feel a slight shock of disbelief. The scenes look not just unreal, but almost deliberately surreal, as if the unexpected conjunction of German and French, French and German, was the result of a Dada prank and not the sober record of history. This shock is merely a distant echo of what the French underwent in 1940: seeing a familiar landscape transformed by the addition of the unfamiliar, living among everyday sights suddenly made bizarre, no longer feeling at home in places they had known all their lives.[21]

Ousby wrote that by the end of summer of 1940: "And so the alien presence, increasingly hated and feared in private, could seem so permanent that, in the public places where daily life went on, it was taken for granted".[22] At the same time France was also marked by disappearances as buildings were renamed, books banned, art was stolen to be taken to Germany and as time went on, people started to vanish.[23]

With nearly 75,000 inhabitants killed and 550,000 tons of bombs dropped, France was, after Germany, the second most severely bomb-devastated country on the Western Front of World War II.[24] Allied bombings were particularly intense before and during Operation Overlord in 1944.

The Allies' Transportation Plan aiming at the systematic destruction of French railway marshalling yards and railway bridges, in 1944, also took a heavy toll on civilian lives. For example, the 26 May 1944 bombing hit railway targets in and around five cities in south-eastern France, causing over 2,500 civilian deaths.[25]

Crossing the ligne de démarcation between the north zone and the south zone also required an Ausweis, which was difficult to acquire.[4] People could write only to their family members, and this was only permissible using a pre-filled card where the sender checked off the appropriate words (e.g. 'in good health', 'wounded', 'dead', 'prisoner').[4] The occupied zone was on German time, which was one hour ahead of the unoccupied zone.[4] Other policies implemented in the occupied zone but not in the free zone were a curfew from 10 p.m to 5 a.m, a ban on American films, the suppression of displaying the French flag and singing the Marseillaise, and the banning of Vichy paramilitary organizations and the Veterans' Legion.[4]

Schoolchildren were made to sing "Maréchal, nous voilà !" ("Marshall, here we are!"). The portrait of Marshal Philippe Pétain adorned the walls of classrooms, thus creating a personality cult. Propaganda was present in education to train the young people with the ideas of the new Vichy regime. However, there was no resumption in ideology as in other occupied countries, for example in Poland, where the teaching elite was liquidated. Teachers were not imprisoned and the programs were not modified overall. In the private Catholic sector, many school directors hid Jewish children (thus saving their life) and provided education for them until the Liberation.[citation needed]

Nightlife in Paris

German soldiers talking with French women by the Moulin Rouge in June 1940, shortly after the German occupation of Paris

One month after the occupation, the bi-monthly soldiers' magazine Der Deutsche Wegleiter für Paris (The German Guide to Paris) was first published by the Paris Kommandantur, and became a success.[26] Further guides, such as the Guide aryien, counted e.g. the Moulin Rouge among the must-see locations in Paris.[27] Famous clubs such as the Folies-Belleville or Bobino were also among the sought-after venues. A wide array of German units were rotated to France to rest and refit; the Germans used the motto "Jeder einmal in Paris" ("everyone once in Paris") and provided 'recreational visits' to the city for their troops.[28] Various famous artists, such as Yves Montand, or later Les Compagnons de la chanson, started their careers during the occupation. Edith Piaf lived above L'Étoile de Kléber, a famous bordello on the Rue Lauriston, which was near to the Carlingue headquarters and often frequented by German troops. The curfew in Paris was not upheld as strictly as in other cities.

The Django Reinhardt song "Nuages", performed by Reinhardt and the Quintet of the Hot Club of France in the Salle Pleyel, gained notoriety among both French and German fans. Reinhardt was even invited to play for the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht.[29] The use and abuse of Paris in the visitations of German forces during the Second World War led to a backlash; the intensive prostitution during the occupation made way for the Loi de Marthe Richard in 1946, which closed the bordellos and reduced raunchy stage shows to mere dancing events.

Oppression

During the German occupation, a forced labour policy, called Service du Travail Obligatoire ("Obligatory work service, STO"), consisted of the requisition and transfer of hundreds of thousands of French workers to Germany against their will, for the German war effort. In addition to work camps for factories, agriculture, and railroads, forced labour was used for V-1 launch sites and other military facilities targeted by the Allies in Operation Crossbow. Beginning in 1942, many refused to be drafted to factories and farms in Germany by the STO, going underground to avoid imprisonment and subsequent deportation to Germany. For the most part, those "work dodgers" (réfractaires) became maquisards.

There were German reprisals against civilians in occupied countries; in France, the Nazis built an execution chamber in the cellars of the former Ministry of Aviation building in Paris.[30]

Many Jews were victims of the Holocaust in France. Approximately 49 concentration camps were in use in France during the occupation, the largest of them at Drancy. In the occupied zone, as of 1942, Jews were required to wear the yellow badge and were only allowed to ride in the last carriage of the Paris Métro. 13,152 Jews residing in the Paris region were victims of a mass arrest by pro-Nazi French authorities on 16 and 17 July 1942, known as the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup, and were transported to Auschwitz where they were killed.[31]

Overall, according to a detailed count drawn under Serge Klarsfeld, slightly below 77,500 of the Jews residing in France died during the war, overwhelmingly after being deported to death camps.[32][33] Out of a Jewish population in France in 1940 of 350,000, this means that somewhat less than a quarter died. While horrific, the mortality rate was lower than in other occupied countries (e.g. 75 percent in the Netherlands) and, because the majority of the Jews were recent immigrants to France (mostly exiles from Germany), more Jews lived in France at the end of the occupation than did approximately 10 years earlier when Hitler formally came to power.[34]

The yellow Star of David made mandatory by the Vichy regime in France

"Jews not admitted here". Sign outside a restaurant in Paris, rue de Choiseul

French Jewish women wearing the yellow badge

German soldiers entering a synagogue in Brest that has been converted into a Soldatenbordell (military brothel → German brothels in occupied France)

Adolf Hitler strolling in front of the Eiffel tower in Paris, 23 June 1940.

Execution chamber inspected by a Parisian policeman and members of the FFI after the liberation.

German road signs in occupied Paris. The Feldgendarmerie was responsible for military traffic.

German soldiers and captured communists, July 1944

Aftermath

The Liberation of France was the result of the Allied operations Overlord and Dragoon in the summer of 1944. Most of France was liberated by September 1944. Some of the heavily fortified French Atlantic coast submarine bases remained stay-behind "fortresses" until the German capitulation in May 1945. The Free French exile government declared the re-establishment of a provisional French Republic, ensuring continuity with the defunct Third Republic. It set about raising new troops to participate in the advance to the Rhine and the invasion of Germany, using the French Forces of the Interior as military cadres and manpower pools of experienced fighters to allow a very large and rapid expansion of the French Liberation Army (Armée française de la Libération). Thanks to Lend-Lease, it was well equipped and well supplied despite the economic disruption brought by the occupation, and it grew from 500,000 men in the summer of 1944 to more than 1.3 million by V-E day, making it the fourth largest Allied army in Europe.[35]

A plaque commemorating the Oath of Kufra near the cathedral of Strasbourg, the capital of Alsace and Elsaß-Lothringen, and after the war, a capital of Europe as a symbol of peace and reconciliation.

The French 2nd Armored Division, tip of the spear of the Free French forces that had participated in the Normandy Campaign and had liberated Paris on 25 August 1944, went on to liberate Strasbourg on 23 November 1944, thus fulfilling the Oath of Kufra made by General Leclerc almost four years earlier. The unit under his command, barely above company-size when it had captured the Italian fort, had grown into a full-strength armoured division.

The spearhead of the Free French First Army, that had landed in Provence on 15 August 1944, was the I Corps. Its leading unit, the French 1st Armored Division, was the first Western Allied unit to reach the Rhône (25 August 1944), the Rhine (19 November 1944) and the Danube (21 April 1945). On 22 April 1945, it captured the Sigmaringen enclave in Baden-Württemberg, where the last Vichy regime exiles, including Marshal Pétain, were hosted by the Germans in one of the ancestral castles of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

Collaborators were put on trial in legal purges (épuration légale), and a number were executed for high treason, among them Pierre Laval, Vichy's prime minister in 1942-44. Marshal Pétain, "Chief of the French State" and Verdun hero, was also condemned to death (14 August 1945), but his sentence was commuted to life three days later.[36]

Thousands of collaborators were summarily executed by local Resistance forces in so-called "savage purges" (épuration sauvage).

See also

- Free France

- Vichy France

- Military Administration (Nazi Germany)

- Paris in World War II

Notes

^ Vinen, Richard (2006). The Unfree French: Life under the Occupation (1st ed.). London: Allen Lane. pp. 105–6. ISBN 978-0-713-99496-4..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Schöttler, Peter (2003). "'Eine Art "Generalplan West": Die Stuckart-Denkschrift vom 14. Juni 1940 und die Planungen für eine neue deutsch-französische Grenze im Zweiten Weltkrieg". Sozial.Geschichte (in German). 18 (3): 83–131.

^ ""La ligne de démarcation", Collection " Mémoire et Citoyenneté ", No.7" (PDF).

[permanent dead link]

^ abcde Jackson, Julian (2003). France: the dark years, 1940-1944. Oxford University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-19-925457-6.

^ The name ligne de démarcation did not figure in the terms of the armistice, but was coined as a translation of the German Demarkationslinie.

^ Giorgio Rochat, (trad. Anne Pilloud), La campagne italienne de juin 1940 dans les Alpes occidentales, Revue historique des armées, No. 250, 2008, pp77-84, sur le site du Service historique de la Défense, rha.revues.org. Mis en ligne le 6 juin 2008, consulté le 24 octobre 2008.

^ « L’occupation italienne », resistance-en-isere.com. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

^ ab La convention d'armistice, sur le site de l'Université de Perpignan, mjp.univ-perp.fr, accessed 29 November 2008.

^ ab Hoffmann, Stanley (1974). "La droite à Vichy". Essais sur la France: déclin ou renouveau?. Paris: Le Seuil.

^ "The Civilian Experience in German Occupied France, 1940-1944". Connecticut College.

^ Peter Lieb: Konventioneller Krieg oder NS-Weltanschauungskrieg? Kriegführung und Partisanenbekämpfung in Frankreich 1943/44, München, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2007,

ISBN 978-3486579925

^ Dear and Foot 2005, p. 321.Dear; Foot (2005). The Oxford Companion to World War II. p. 321.

^ g, J. (1942). "Statistiques récentes [La population de la France d'après le recensement du 1er avril 1941]". Annales de Géographie. 51 (286): 155–156.

^ The American Historical Association. "Book Review of Morts d'inanition: Famine et exclusions en France sous l'Occupation". Archived from act=justtop&url=http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/111.5/br_161.html the original Check|url=value (help) on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

^ Marie Helen Mercier and J. Louise Despert. "Effects of War on French children" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-12-15.

^ E. M. Collingham , The Taste of War: World War Two and the Battle for Food (2011)

^ Kenneth Mouré, "Food Rationing and the Black Market in France (1940-1944)," French History, June 2010, Vol. 24 Issue 2, pp. 272-273

^ Mouré, "Food Rationing and the Black Market in France (1940-1944)" pp 262-282,

^ Ousby, Ian Occupation The Ordeal of France, 1940-1944, New York: CooperSquare Press, 2000 pages 157-159.

^ Ousby, Ian Occupation The Ordeal of France, 1940-1944, New York: CooperSquare Press, 2000 page 159.

^ Ousby, Ian Occupation The Ordeal of France, 1940-1944, New York: CooperSquare Press, 2000 page 158.

^ Ousby, Ian Occupation The Ordeal of France, 1940-1944, New York: CooperSquare Press, 2000 page 170.

^ Ousby, Ian Occupation The Ordeal of France, 1940-1944, New York: CooperSquare Press, 2000 pages 171, 18 & 187-189.

^ Centre d'études d'histoire de la défense, Les bombardements alliés sur la France durant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, Stratégies, bilans matériels et humains, Conference of 6 June 2007, Defense.gouv.fr Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine. retrieved 5 November 2009

^ See French language Wikipedia article fr:bombardement du 26 mai 1944

^ Hetch, Emmanuel (October 2013). "Le Guide du soldat allemand à Paris, ou comment occuper Fritz". L'Express (in French). Retrieved 23 October 2013.

^ Emotion in Motion: Tourism, Affect and Transformation, Dr David Picard, Professor Mike Robinson, Ashgate Publishing, 2012,

ISBN 978-14094-2133-7

^ Paris under the occupation, Gilles Perrault; Jean-Pierre Azéma London : Deutsch, 1989,

ISBN 978-0-233-98511-4.

^ Michael Dregni: Django – The Life and Music of a Gipsy Legend. p.344, Oxford University Press, 2006,

ISBN 978-01951-6752-8

^ "NAZI PERSECUTION". Imperial War Museum. 2011. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

^ Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence: Case Study: The Vélodrome d'Hiver Round-up: July 16 and 17, 1942

^ Summary from data compiled by the Association des Fils et Filles des déportés juifs de France, 1985.

^ Azéma, Jean-Pierre and Bédarida, François (dir.), La France des années noires, 2 vol., Paris, Seuil, 1993 [rééd. Seuil, 2000 (Points Histoire)]

^ François Delpech, Historiens et Géographes, no 273, mai–juin 1979,

ISSN 0046-757X

^ Talbot, C. Imlay; Duffy Toft, Monica (2007-01-24). The Fog of Peace and War Planning: Military and Strategic Planning Under Uncertainty. Routledge, 2007. p. 227. ISBN 9781134210886.

^ by de Gaulle, then leader of the Provisional Government of the French Republic

Further reading

- Isabelle von Bueltzingsloewen, (ed) (2005). "Morts d'inanition": Famine et exclusions en France sous l'Occupation. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

ISBN 2-7535-0136-X

Philippe Burrin (1998). France Under the Germans: Collaboration and Compromise. New York: New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584-439-1.

Robert Gildea (2002). Marianne in Chains: In Search of the German Occupation 1940–1945. London: Macmillan.

ISBN 978-0-333-78230-9

Gerhard Hirschfeld & Patrick Marsh (eds) (1989). Collaboration in France: Politics and Culture during the Nazi Occupation 1940-1944. Berg Pub,

ISBN 978-0854962372

Julian T. Jackson (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-820706-9

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Convention d’armistice du 22 juin 1940 |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Adolf Hitler's Appeal to the French People on the Entry of German Troops into Unoccupied France |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Adolf Hitler's Letter to Marshal Petain Announcing Complete German Occupation of France |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Adolf Hitler's Letter to Marshal Petain Announcing Decision to Occupy Toulon |

Cliotexte: sources on collaboration and resistance (in French)

Cliotexte: daily life under occupation (in French)

- NAZI diplomacy: Vichy, 1940

- unwelcome visitor is a webpage relating Hitler's triumphal tour of Paris.