Socialist realism

At the Museum of Socialist Art, Sofia, Bulgaria

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was imposed as the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II.[1] Socialist realism is characterized by the glorified depiction of communist values, such as the emancipation of the proletariat, by means of realistic imagery.[2] Although related, it should not be confused with social realism, a type of art that realistically depicts subjects of social concern.[3]

Socialist realism was the predominant form of approved art in the Soviet Union from its development in the early 1920s to its eventual fall from official status beginning in the late 1960s until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991.[4][5] While other countries have employed a prescribed canon of art, socialist realism in the Soviet Union persisted longer and was more restrictive than elsewhere in Europe.[6]

Contents

1 Development

1.1 Debate within Soviet art

2 Characteristics

3 Important groups

3.1 Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR)

3.2 Society of Easel Painters (OSt)

4 Impact

5 Notable works and artists

6 Soviet Union

7 Other socialist states

8 Painting

9 Sculpture

10 See also

11 References

12 Further reading

13 External links

Development

Detail, Der Weg der Roten Fahne, Kulturpalast Dresden, Germany

Socialist realism was developed by many thousands of artists, across a diverse society, over several decades.[7] Early examples of realism in Russian art include the work of the Peredvizhnikis and Ilya Yefimovich Repin. While these works do not have the same political connotation, they exhibit the techniques exercised by their successors. After the Bolsheviks took control of Russia on October 25, 1917, there was a marked shift in artistic styles. There had been a short period of artistic exploration in the time between the fall of the Tsar and the rise of the Bolsheviks.

Shortly after the Bolsheviks took control, Anatoly Lunacharsky was appointed as head of Narkompros, the People's Commissariat for Enlightenment.[7] This put Lunacharsky in the position of deciding the direction of art in the newly created Soviet state. Although Lunacharsky did not dictate a single aesthetic model for Soviet artists to follow, he developed a system of aesthetics based on the human body that would later help to influence socialist realism. He believed that "the sight of a healthy body, intelligent face or friendly smile was essentially life-enhancing."[8] He concluded that art had a direct effect on the human organism and under the right circumstances that effect could be positive. By depicting "the perfect person" (New Soviet man), Lunacharsky believed art could educate citizens on how to be the perfect Soviets.[8]

Debate within Soviet art

First Lenin statue built by the workers in Noginsk

There were two main groups debating the fate of Soviet art: futurists and traditionalists. Russian Futurists, many of whom had been creating abstract or leftist art before the Bolsheviks, believed communism required a complete rupture from the past and, therefore, so did Soviet art.[8] Traditionalists believed in the importance of realistic representations of everyday life. Under Lenin's rule and the New Economic Policy, there was a certain amount of private commercial enterprise, allowing both the futurists and the traditionalists to produce their art for individuals with capital.[9] By 1928, the Soviet government had enough strength and authority to end private enterprises, thus ending support for fringe groups such as the futurists. At this point, although the term "socialist realism" was not being used, its defining characteristics became the norm.[10]

The first time the term "socialist realism" was officially used was in 1932. The term was settled upon in meetings that included politicians of the highest level, including Stalin himself.[11]Maxim Gorky, a proponent of literary socialist realism, published a famous article titled "Socialist Realism" in 1933 and by 1934 the term's etymology was traced back to Stalin.[11] During the Congress of 1934, four guidelines were laid out for socialist realism.[12]

The work must be:

- Proletarian: art relevant to the workers and understandable to them.

- Typical: scenes of everyday life of the people.

- Realistic: in the representational sense.

- Partisan: supportive of the aims of the State and the Party.

Characteristics

Worker and Kolkhoz Woman by Vera Mukhina (1937)

Workers inspect architectural model under a statue of Stalin, Leipzig, East Germany, 1953.

The purpose of socialist realism was to limit popular culture to a specific, highly regulated faction of emotional expression that promoted Soviet ideals.[13] The party was of the utmost importance and was always to be favorably featured. The key concepts that developed assured loyalty to the party, "partiinost'" (party-mindedness), "ideinost" (idea- or ideological-content), "klassovost" (class content), "pravdivost" (truthfulness).[14]

There was a prevailing sense of optimism, socialist realism's function was to show the ideal Soviet society. Not only was the present gloried, but the future was also supposed to be depicted in an agreeable fashion. Because the present and the future were constantly idealized, socialist realism had a sense of forced optimism. Tragedy and negativity were not permitted, unless they were shown in a different time or place. This sentiment created what would later be dubbed "revolutionary romanticism."[14]

Revolutionary romanticism elevated the common worker, whether factory or agricultural, by presenting his life, work, and recreation as admirable. Its purpose was to show how much the standard of living had improved thanks to the revolution. Art was used as educational information. By illustrating the party's success, artists were showing their viewers that sovietism was the best political system. Art was also used to show how Soviet citizens should be acting. The ultimate aim was to create what Lenin called "an entirely new type of human being": The New Soviet Man. Art (especially posters and murals) was a way to instill party values on a massive scale. Stalin described the socialist realist artists as "engineers of souls."[15]

Common images used in socialist realism were flowers, sunlight, the body, youth, flight, industry, and new technology.[14] These poetic images were used to show the utopianism of communism and the Soviet state. Art became more than an aesthetic pleasure; instead it served a very specific function. Soviet ideals placed functionality and work above all else; therefore, for art to be admired, it must serve a purpose. Georgi Plekhanov, a Marxist theoretician, states that art is useful if it serves society: "There can be no doubt that art acquired a social significance only in so far as it depicts, evokes, or conveys actions, emotions and events that are of significance to society."[16]

The artist could not, however, portray life just as they saw it because anything that reflected poorly on Communism had to be omitted. People who could not be shown as either wholly good or wholly evil could not be used as characters.[17] This was reflective of the Soviet idea that morality is simple: things are either right or wrong. This view on morality called for idealism over realism.[15] Art was filled with health and happiness: paintings showed busy industrial and agricultural scenes; sculptures depicted workers, sentries, and schoolchildren.[18]

Creativity was not an important part of socialist realism: it was actually rejected. The styles used in creating art during this period were those that would produce the most realistic results. Painters would depict happy, muscular peasants and workers in factories and collective farms. During the Stalin period, they produced numerous heroic portraits of the dictator to serve his cult of personality—all in the most realistic fashion possible.[19] The most important thing for a socialist realist artist was not artistic integrity but adherence to party doctrine.[13] The results were often sentimental kitsch. (Citation needed)

Important groups

Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR)

The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR) was established in 1922 and was one of the most influential artist groups in the USSR. The AKhRR worked to truthfully document contemporary life in Russia by utilizing "heroic realism".[9] The term "heroic realism" was beginning of the socialist realism archetype. AKhRR was sponsored by influential government officials such as Leon Trotsky and carried favor with the Red Army.[9]

In 1928, the AKhRR was renamed to Association of Artists of the Revolution (AKhR) in order to include the rest of the Soviet states. At this point the group had begun participating in state promoted mass forms of art like murals, jointly made paintings, advertisement production and textile design.[20] The group was disbanded April 23, 1932 by the decree "On the Reorganization of Literary and Artistic Organizations"[20] serving as the nucleus for the stalinist USSR Union of Artists.

Society of Easel Painters (OSt)

While the Society of Easel Painters (OSt) was also focused on the glorification of the revolution they, as per their name, worked individually as easel painters. The most common subjects of the OSt's works fit with the developing socialist realism trope. Their paintings consisted of sport and battle, industry and modern technology.[21]

The OSt broke up in 1931 due to some members' demand to transition to collective print and poster work.[21] Some prominent members include Aleksandr Deyneka (till 1928), Yuri Pimanov, Aleksandr Labas, Pyotr Vilyams, all of whom were students or ex-students of Moscow's art school, Vkhutemas.[22]

Impact

A monumental obelisk surrounded by sculptures of soldiers at the Soviet military cemetery in Warsaw

The impact of socialist realism art can still be seen and felt decades after it was no longer the only state supported style. Even before the end of the USSR in 1991, the government had been loosening its hold on censorship. After Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev began to condemn the previous regime's practice of excessive restrictions. This freedom allowed artists to begin experimenting with new techniques, but the shift was not immediate. It was not until the ultimate fall of Soviet rule that artists were no longer restricted by the communist party. Many socialist realism tendencies prevailed until the mid-to-late 1990s and early 2000s.[23]

In the 1990s, many Russian artists used socialist realism characteristics in an ironic fashion.[23] This was a complete rupture from what existed only a couple of decades before. Once artists broke from the socialist realism mold there was a significant power shift. Artists began including subjects that could not exist according to Soviet ideals. Now that the power over appearances was taken away from the government, artists achieved a level of authority that had not existed since the early 20th century.[24] In the decade immediately after the fall of the USSR, artists represented socialist realism and the Soviet legacy as a traumatic event. By the next decade, there was a unique sense of detachment.[25]

Western cultures often do not look at socialist realism positively. Democratic countries view the art produced during this period of repression as a lie.[26] Non-Marxist cultures tend to view communism as a form of totalitarianism that smothers artistic expression and therefore retards the progress of culture.[27] Western cultures often look at socialist realistic works as propaganda rather than art. Artistically it could be seen as grandiose, and as sentimental kitsch.

Notable works and artists

"Soldier-Liberator" by Yevgeny Vuchetich. Treptower Park Memorial, Berlin (1948-1949)

Maxim Gorky's novel Mother is usually considered[by whom?] to have been the first socialist-realist novel.[citation needed] Gorky was also a major factor in the school's rapid rise, and his pamphlet, On Socialist Realism, essentially lays out the needs of Soviet art. Other important works of literature include Fyodor Gladkov's Cement (1925), Nikolai Ostrovsky's How the Steel Was Tempered and Mikhail Sholokhov's two volume epic, Quiet Flows the Don (1934) and The Don Flows Home to the Sea (1940). Yury Krymov's novel Tanker "Derbent" (1938) portrays Soviet merchant seafarers being transformed by the Stakhanovite movement.

Martin Andersen Nexø developed socialist realism in his own way. His creative method featured a combination of publicistic passion, a critical view of capitalist society, and a steadfast striving to bring reality into accord with socialist ideals. The novel Pelle, the Conqueror is considered to be a classic of socialist realism.[citation needed] The novel Ditte, Daughter of Man had a working-class woman as its heroine. He battled against the enemies of socialism in the books Two Worlds, and Hands Off!.

The novels of Louis Aragon, such as The Real World, depict the working class as a rising force of the nation. He published two books of documentary prose, The Communist Man. In the collection of poems A Knife in the Heart Again, Aragon criticizes the penetration of American imperialism into Europe. The novel The Holy Week depicts the artist's path toward the people against a broad social and historical background.[citation needed]

Hanns Eisler composed many workers' songs, marches, and ballads on current political topics such as Song of Solidarity, Song of the United Front, and Song of the Comintern. He was a founder of a new style of revolutionary song for the masses. He also composed works in larger forms such as Requiem for Lenin. Eisler's most important works include the cantatas German Symphony, Serenade of the Age and Song of Peace. Eisler combines features of revolutionary songs with varied expression. His symphonic music is known for its complex and subtle orchestration.

Closely associated with the rise of the labor movement was the development of the revolutionary song, which was performed at demonstrations and meetings. Among the most famous of the revolutionary songs are The Internationale and Whirlwinds of Danger. Notable songs from Russia include Boldly, Comrades, in Step, Workers' Marseillaise, and Rage, Tyrants. Folk and revolutionary songs influenced the Soviet mass songs. The mass song was a leading genre in Soviet music, especially during the 1930s and the war. The mass song influenced other genres, including the art song, opera, and film music. The most popular mass songs include Dunaevsky's Song of the Homeland, Blanter's Katiusha, Novikov's Hymn of Democratic Youth of the World, and Aleksandrov's Sacred War.

In the early 1930s, Soviet filmmakers applied socialist realism in their work. Notable films include Chapaev, which shows the role of the people in the history-making process. The theme of revolutionary history was developed in films such as The Youth of Maxim, by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg, Shchors by Dovzhenko, and We are from Kronstadt by E. Dzigan. The shaping of the new man under socialism was a theme of films such as A Start Life by N. Ekk, Ivan by Dovzhenko, Valerii Chkalov by M. Kalatozov and the film version of Tanker "Derbent" (1941). Some films depicted the part of peoples of the Soviet Union against foreign invaders: Alexander Nevsky by Eisenstein, Minin and Pozharsky by Pudvokin, and Bogdan Khmelnitsky by Savchenko. Soviet politicians were the subjects in films such as Yutkevich's trilogy of movies about Lenin.

Socialist realism was also applied to Hindi films of the 1940s and 1950s.[citation needed] These include Chetan Anand's Neecha Nagar (1946), which won the Grand Prize at the 1st Cannes Film Festival, and Bimal Roy's Two Acres of Land (1953), which won the International Prize at the 7th Cannes Film Festival.

The painter Aleksandr Deineka provides a notable example for his expressionist and patriotic scenes of the Second World War, collective farms, and sports. Yuriy Pimenov, Boris Ioganson and Geli Korzev have also been described as "unappreciated masters of twentieth-century realism".[28] Another well-known practitioner was Fyodor Pavlovich Reshetnikov.

Socialist realism art found acceptance in the Baltic nations, inspiring many artists. One such artist was Czeslaw Znamierowski (23 May 1890 – 9 August 1977), a Soviet Lithuanian painter, known for his large panoramic landscapes and love of nature. Znamierowski combined these two passions to create very notable paintings in the Soviet Union, earning the prestigious title of Honorable Artist of LSSR in 1965.[29] Born in Latvia, which formed part of the Russian Empire at the time, Znamierowski was of Polish nationality and Lithuanian citizenship, a country where he lived for most of his life and died. He excelled in landscapes and social realism, and held many exhibitions. Znamierowski was also widely published in national newspapers, magazines and books.[30] His more notable paintings include Before Rain (1930), Panorama of Vilnius City (1950), The Green Lake (1955), and In Klaipeda Fishing Port (1959).A large collection of his art is located in the Lithuanian Art Museum.[31]

Thol, a novel by D. Selvaraj in Tamil is a standing example of Marxist Realism in India. It won a literary award (Sahithya Akademi) for the year 2012.

Soviet Union

The All-Russia Exhibition Centre in Moscow.

In conjunction with the Socialist Classical style of architecture, socialist realism was the officially approved type of art in the Soviet Union for more than fifty years.[32] All material goods and means of production belonged to the community as a whole; this included means of producing art, which were also seen as powerful propaganda tools.[citation needed]

In the early years of the Soviet Union, Russian and Soviet artists embraced a wide variety of art forms under the auspices of Proletkult. Revolutionary politics and radical non-traditional art forms were seen as complementary.[33] In art, Constructivism flourished. In poetry, the non-traditional and the avant-garde were often praised.

These styles of art were later rejected by members of the Communist Party who did not appreciate modern styles such as Impressionism and Cubism. Socialist realism was, to some extent, a reaction against the adoption of these "decadent" styles. It was thought by Lenin that the non-representative forms of art were not understood by the proletariat and could therefore not be used by the state for propaganda.[34]

Alexander Bogdanov argued that the radical reformation of society to communist principles meant little if any bourgeois art would prove useful; some of his more radical followers advocated the destruction of libraries and museums.[35] Lenin rejected this philosophy,[36] deplored the rejection of the beautiful because it was old, and explicitly described art as needing to call on its heritage: "Proletarian culture must be the logical development of the store of knowledge mankind has accumulated under the yoke of capitalist, landowner, and bureaucratic society."[37]

Modern art styles appeared to refuse to draw upon this heritage, thus clashing with the long realist tradition in Russia and rendering the art scene complex.[38] Even in Lenin's time, a cultural bureaucracy began to restrain art to fit propaganda purposes.[39]Leon Trotsky's arguments that a "proletarian literature" was un-Marxist because the proletariat would lose its class characteristics in the transition to a classless society, however, did not prevail.[40]

A mosaic of Lenin inside the Moscow Metro.

Socialist realism became state policy in 1934 when the First Congress of Soviet Writers met and Stalin's representative Andrei Zhdanov gave a speech strongly endorsing it as "the official style of Soviet culture".[41] It was enforced ruthlessly in all spheres of artistic endeavour. Form and content were often limited, with erotic, religious, abstract, surrealist, and expressionist art being forbidden. Formal experiments, including internal dialogue, stream of consciousness, nonsense, free-form association, and cut-up were also disallowed. This was either because they were "decadent", unintelligible to the proletariat, or counter-revolutionary.

In response to the 1934 Congress in Russia, the most important American writers of the left gathered in the First American Writers Congress of 26–27 April 1935 in Chicago at meetings that were supported by Stalin. Waldo David Frank was the first president of the League of American Writers, which was backed by the Communist Party USA. A number of novelists balked at the control, and the League broke up at the invasion of the Soviet Union by German forces.[citation needed]

The first exhibition organized by the Leningrad Union of Artists took place in 1935.[citation needed] Its participants – Mikhail Avilov, Isaak Brodsky, Piotr Buchkin, Nikolai Dormidontov, Rudolf Frentz, Kazimir Malevich, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, and Alexander Samokhvalov among them – became the founding fathers of the Leningrad school, while their works formed one of its richest layers and the basis of the largest museum collections of Soviet painting of the 1930s-1950s.[citation needed]

A portrait of Stalin by Isaak Brodsky.

In 1932, the Leningrad Institute of Proletarian Visual Arts was transformed into the Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (since 1944 named Ilya Repin). The fifteen-year period of constant reformation of the country's largest art institute came to an end.[citation needed] Thus, basic elements of the Leningrad school – namely, a higher art education establishment of a new type and a unified professional union of Leningrad artists, were created by the end of 1932.[citation needed]

In 1934 Isaak Brodsky, a disciple of Ilya Repin, was appointed director of the National Academy of Arts and the Leningrad Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture.[citation needed] Brodsky invited distinguished painters and pedagogues to teach at the Academy, namely Semion Abugov, Mikhail Bernshtein, Ivan Bilibin, Piotr Buchkin, Efim Cheptsov, Rudolf Frentz, Boris Ioganson, Dmitry Kardovsky, Alexander Karev, Dmitry Kiplik, Yevgeny Lansere, Alexander Lubimov, Matvey Manizer, Vasily Meshkov, Pavel Naumov, Alexander Osmerkin, Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, Leonid Ovsyannikov, Nikolai Petrov, Sergei Priselkov, Nikolay Punin, Nikolai Radlov, Konstantin Rudakov, Pavel Shillingovsky, Vasily Shukhaev, Victor Sinaisky, Ivan Stepashkin, Konstantin Yuon, and others.[citation needed]

Art exhibitions of 1935–1940 serve as counterpoint to claims that the artistic life of the period was suppressed by the ideology and artists submitted entirely to what was then called "social order". A great number of landscapes, portraits, and genre paintings exhibited at the time pursued purely technical purposes and were thus ostensibly free from any ideology. Genre painting was also approached in a similar way.[42]

In the post-war period between the mid-fifties and sixties, the Leningrad school of painting was approaching its vertex.[citation needed] New generations of artists who had graduated from the Academy (Repin Institute of Arts) in the 1930s–50s were in their prime.[citation needed] They were quick to present their art, they strived for experiments, and were eager to appropriate a lot and to learn even more.[citation needed]

Their time and contemporaries, with all its images, ideas, and dispositions found it full expression in portraits by Vladimir Gorb, Boris Korneev, Engels Kozlov, Felix Lembersky, Oleg Lomakin, Samuil Nevelshtein, Victor Oreshnikov, Semion Rotnitsky, Lev Russov, and Leonid Steele; in landscapes by Nikolai Galakhov, Vasily Golubev, Dmitry Maevsky, Sergei Osipov, Vladimir Ovchinnikov, Alexander Semionov, Arseny Semionov, and Nikolai Timkov; and in genre paintings by Andrey Milnikov, Yevsey Moiseenko, Mikhail Natarevich, Yuri Neprintsev, Nikolai Pozdneev, Mikhail Trufanov, Yuri Tulin, Nina Veselova, and others.[citation needed]

In 1957, the first all-Russian Congress of Soviet artists took place in Moscow.[citation needed] In 1960, the all-Russian Union of Artists was organized.[citation needed] Accordingly, these events influenced the art life in Moscow, Leningrad, and the provinces.[citation needed] The scope of experimentation was broadened; in particular, this concerned the form of painterly and plastic language. Images of youths and students, rapidly changing villages and cities, virgin lands brought under cultivation, grandiose construction plans being realized in Siberia and the Volga region, and great achievements of Soviet science and technology became the chief topics of the new painting. Heroes of the time – young scientists, workers, civil engineers, physicians, etc. – were made the most popular heroes of paintings.[citation needed]

The system breaks down: Erich Honecker, leader of the DDR, views a sculpture not in the style in 1987.

In this period, life provided artists with plenty of thrilling topics, positive figures, and images. Legacy of many great artists and art movements became available for study and public discussion again. This greatly broadened artists' understanding of the realist method and widened its possibilities. It was the repeated renewal of the very conception of realism that made this style dominate Russian art throughout its history. Realist tradition gave rise to many trends of contemporary painting, including painting from nature, "severe style" painting, and decorative art. However, during this period impressionism, postimpressionism, cubism, and expressionism also had their fervent adherents and interpreters.[43]

The restrictions were relaxed somewhat after Stalin's death in 1953, but the state still kept a tight rein on personal artistic expression.[citation needed] This caused many artists to choose to go into exile, for example the Odessa Group from the city of that name.[citation needed] Independent-minded artists that remained continued to feel the hostility of the state.

In 1974, for instance, a show of unofficial art in a field near Moscow was broken up and the artwork destroyed with a water cannon and bulldozers (see Bulldozer Exhibition). Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of glasnost and perestroika facilitated an explosion of interest in alternative art styles in the late 1980s, but socialist realism remained in limited force as the official state art style until as late as 1991. It was not until after the fall of the Soviet Union that artists were finally freed from state censorship.[citation needed]

Other socialist states

The people of Wuhan fighting the flood of 1954, as depicted on a monument erected in 1969

Murals displaying the Marxist view of the press on this East Berlin cafe in 1977 were covered over by commercial advertising after Germany was reunited.

After the Russian Revolution, socialist realism became an international literary movement. Socialist trends in literature were established in the 1920s in Germany, France, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. Writers who helped develop socialist realism in the West included Louis Aragon, Johannes Becher, and Pablo Neruda.[44]

The doctrine of socialist realism in other People's Republics, was legally enforced from 1949 to 1956. It involved all domains of visual and literary arts, though its most spectacular achievements were made in the field of architecture, considered a key weapon in the creation of a new social order, intended to help spread the communist doctrine by influencing citizens' consciousness as well as their outlook on life. During this massive undertaking, a crucial role fell to architects perceived not as merely engineers creating streets and edifices, but rather as "engineers of the human soul" who, in addition to extending simple aesthetics into urban design, were to express grandiose ideas and arouse feelings of stability, persistence and political power.

Today, arguably the only countries still focused on these aesthetic principles are North Korea, Laos, and to some extent Vietnam. The People's Republic of China occasionally reverts to socialist realism for specific purposes, such as idealised propaganda posters to promote the Chinese space program. Socialist realism had little mainstream impact in the non-Communist world, where it was widely seen as a totalitarian means of imposing state control on artists.[45]

The former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was an important exception among the communist countries, because after the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, it abandoned socialist realism along with other elements previously imported from the Soviet system and allowed greater artistic freedom.[46]Miroslav Krleža, one of the leading Yugoslav intellectuals, gave a speech at the Third Congress of the Writers Alliance of Yugoslavia held in Ljubljana in 1952, which is considered a turning point in the Yugoslav denouncement of dogmatic socialist realism.[citation needed]

Painting

N. Kasatkin. Pioneer-girl with book (1926)

Vladimir Pchelin, Lenin Assassination Attempt (1927)

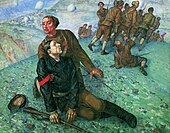

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, The death of the Political Commissar (1928)

Sergey Malyutin, Partisan

Mitrofan Grekov, Trumpeter and standard-bearer (1934)

Isaak Brodsky, Lenin in Smolny (1930)

The Green Lake by Czeslaw Znamierowski, 145 x 250 cm, 1955

Female Partisan in Battle, National History Museum, Tirana, Albania

Sculpture

Socialist-Realist allegories surrounding the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw.

Sculpture in Vilnius Lithuania, removed in 2015.

Stone as a Weapon of the Proletariat by Ivan Shadr (1947)

Stalin Monument in Prague-Letná (1955–1962)

Negba monument in Israel, (1953)

See also

- Social realism

- Capitalist realism

- Art of the Third Reich

- Heroic realism

- Socialist realism in Romania

- Socialist realism in Poland

- Proletkult

- Fine Art of Leningrad

- Leningrad School of Painting

- Propaganda in the Soviet Union

- Zhdanov Doctrine

References

^ Encyclopedia Britannica on-line definition of Socialit Realism

^ Korin, Pavel, "Thoughts on Art", Socialist Realism in Literature and Art. Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1971, p. 95.

^ Todd, James G. "Social Realism". Art Terms. Museum of Modern Art, 2009.

^ Encyclopedia Britannica on-line definition of Socialist Realism

^ Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 20

^ Valkenier, Elizabeth. Russian Realist Art. Ardis, 1977, p. 3.

^ ab Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 17

^ abc Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 21

^ abc Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 22

^ Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 23

^ ab Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 37

^ Juraga, Dubravka and Booker, Keith M. Socialist Cultures East and West. Praeger, 2002, p.68

^ ab Nelson, Cary and Lawrence, Grossberg. Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. University of Illinois Press, 1988, p. 5

^ abc Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 38

^ ab Overy, Richard. The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W. W. Norton & Company, 2004, p. 354

^ Schwartz, Lawrence H. Marxism and Culture. Kennikat Press, 1980, p. 110

^ Frankel, Tobia. The Russian Artist. Macmillan Company, 1972, p. 125

^ Stegelbaum, Lewis and Sokolov, Andrei. Stalinism As A Way Of Life. Yale University Press, 2004, p. 220

^ Juraga, Dubravka and Booker, Keith M. Socialist Cultures East and West. Praeger, 2002, p.45

^ ab Ellis, Andrew. Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 35

^ ab Nelson, Cary and Lawrence, Grossberg. Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. University of Illinois Press, 1988, p. 93

^ Nelson, Cary and Lawrence, Grossberg. Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. University of Illinois Press, 1988, p. 92

^ ab Evangeli, Aleksandr. "Echoes of Socialist Realism in Post-Soviet Art", Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 218

^ Evangeli, Aleksandr. "Echoes of Socialist Realism in Post-Soviet Art", Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 221

^ Evangeli, Aleksandr. "Echoes of Socialist Realism in Post-Soviet Art", Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920–1970. Skira Editore S.p.A., 2012, p. 223

^ Juraga, Dubravka and Booker, Keith M. Socialist Cultures East and West. Praeger, 2002, p.12

^ Schwartz, Lawrence H. Marxism and Culture. Kennikat Press, 1980, p. 4

^ Bartelik,, Marek (1999). "Concerning Socialist Realism: Recent Publications on Russian Art (book review)". Art Journal. Archived from the original on 2004-11-23..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Alekna, Romas (24 May 1975). "Česlovui Znamierovskiui - 85" [Česlovas Znamierovskis Celebrates his 85th Birthday]. Literatūra ir menas [Literature and Art] (in Lithuanian) (Vilnius: Lithuanian Creative Unions Weekly)

^ "Czeslaw Znamierowski". CzeslawZnamierowski. 27 October 2013.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2013-11-20.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Ellis, Andrew (2012). Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920-1970. Skira Editore S.p.A. p. 20.

^ Werner Haftmann, Painting in the 20th century, London 1965, vol.1, p.196.

^ Haftman, p.196

^ Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, p. 288,

ISBN 978-0-394-50242-7

^ Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, p. 289,

ISBN 978-0-394-50242-7

^ Oleg Sopontsinsky, Art in the Soviet Union: Painting, Sculpture, Graphic Arts, p 6 Aurora Art Publishers, Leningrad, 1978

^ Oleg Sopontsinsky, Art in the Soviet Union: Painting, Sculpture, Graphic Arts, p. 21 Aurora Art Publishers, Leningrad, 1978

^ Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, p283,

ISBN 978-0-394-50242-7

^ R. H. Stacy, Russian Literary Criticism p191

ISBN 0-8156-0108-5

^ "1934: Writers' Congress". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

^ Sergei V. Ivanov, Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School,[full citation needed]: pp. 29, 32–340.

ISBN 5-901724-21-6,

ISBN 978-5-901724-21-7.

^ Sergei V. Ivanov, The Leningrad School of painting 1930–1990s. Historical outline.[full citation needed]

^ D.F. Markov and L.I. Timofeev, "Socialist Realism"

^ Lin Jung-hua. Post-Soviet Aestheticians Rethinking Russianization and Chinization of Marxism//Russian Language and Literature Studies. Serial № 33. Beijing, Capital Normal University, 2011, №3. Р.46-53.

^ Library of Congress Country Studies – Yugoslavia: Introduction of Socialist Self-Management

Further reading

- Bek, Mikuláš; Chew, Geoffrey; and Macel, Petr (eds.). Socialist Realism and Music. Musicological Colloquium at the Brno International Music Festival 36. Prague: KLP; Brno: Institute of Musicology, Masaryk University, 2004.

ISBN 80-86791-18-1

- Golomstock, Igor. Totalitarian Art in the Soviet Union, the Third Reich, Fascist Italy and the People's Republic of China, Harper Collins, 1990.

- James, C. Vaughan. Soviet Socialist Realism: Origins and Theory. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1973.

- Ivanov, Sergei. Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School. Saint Petersburg, NP-Print, 2007

ISBN 978-5-901724-21-7

- Lin Jung-hua. Post-Soviet Aestheticians Rethinking Russianization and Chinization of Marxism (Russian Language and Literature Studies. Serial № 33) Beijing, Capital Normal University, 2011, №3. Р.46-53.

- Prokhorov, Gleb. Art under Socialist Realism: Soviet Painting, 1930–1950. East Roseville, NSW, Australia: Craftsman House; G + B Arts International, 1995.

ISBN 976-8097-83-3

- Rideout, Walter B. The Radical Novel in the United States: 1900–1954. Some Interrelations of Literature and Society. New York: Hill and Wang, 1966.

- Saehrendt, Christian. Kunst als Botschafter einer künstlichen Nation ("Art from an artificial nation – about modern art as a tool of the GDR's propaganda"), Stuttgart 2009

Sinyavsky, Andrei [writing as Abram Tertz]. "The Trial Begins" and "On Socialist Realism", translated by Max Hayward and George Dennis, with an introduction by Czesław Miłosz. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960–1982.

ISBN 0-520-04677-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Socialist realism. |

- Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden: Socialist Realist Art Conference

- Marxists.org Socialist Realism page

- Virtual Museum of Political Art – Socialist Realism

Sergei V. Ivanov. The Leningrad School of painting. Historical outline.

Research Guide to Russian Art[permanent dead link]

- Socialist realism: Socialist in content, capitalist in price