Israelites

Mosaic of the 12 Tribes of Israel, from a synagogue wall in Jerusalem

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

The Tribes |

|

Related topics |

|

The Israelites (/ˈɪzriəlaɪts/; Hebrew: בני ישראל Bnei Yisra'el)[1] were a confederation of Iron Age Semitic-speaking tribes of the ancient Near East, who inhabited a part of Canaan during the tribal and monarchic periods.[2][3][4][5][6] According to the religious narrative of the Hebrew Bible, the Israelites' origin is traced back to the Biblical patriarchs and matriarchs Abraham and his wife Sarah, through their son Isaac and his wife Rebecca, and their son Jacob who was later called Israel, whence they derive their name, with his wives Leah and Rachel and the handmaids Zilpa and Bilhah.

Modern archaeology has largely discarded the historicity of the religious narrative,[7] with it being reframed as constituting an inspiring national myth narrative. The Israelites and their culture, according to the modern archaeological account, did not overtake the region by force, but instead branched out of the indigenous Canaanite peoples that long inhabited the Southern Levant, Syria, ancient Israel, and the Transjordan region[8][9][10] through the development of a distinct monolatristic—later cementing as monotheistic—religion centered on Yahweh, one of the Ancient Canaanite deities. The outgrowth of Yahweh-centric belief, along with a number of cultic practices, gradually gave rise to a distinct Israelite ethnic group, setting them apart from other Canaanites.[11][12][13]

In the Hebrew Bible the term Israelites is used interchangeably with the term Twelve Tribes of Israel. Although related, the terms Hebrews, Israelites, and Jews are not interchangeable in all instances. "Israelites" (Yisraelim) refers specifically to the direct descendants of any of the sons of the patriarch Jacob (later called Israel), and his descendants as a people are also collectively called "Israel", including converts to their faith in worship of the god of Israel, Yahweh. "Hebrews" (ʿIvrim), on the contrary, is used to denote the Israelites' immediate forebears who dwelt in the land of Canaan, the Israelites themselves, and the Israelites' ancient and modern descendants (including Jews and Samaritans). "Jews" (Yehudim) is used to denote the descendants of the Israelites who coalesced when the Tribe of Judah absorbed the remnants of various other Israelite tribes. Thus, for instance, Abraham was a Hebrew but he was not technically an Israelite nor a Jew, Jacob was both a Hebrew and the first Israelite but not a Jew, while David (as a member of the Tribe of Judah) was all three, a Hebrew, an Israelite, and a Judahite (Yehudi, Jew). A Samaritan, on the contrary, while being both a Hebrew and an Israelite, is not a Jew.

During the period of the divided monarchy "Israelites" was only used to refer to the inhabitants of the northern Kingdom of Israel, and it is only extended to cover the people of the southern Kingdom of Judah in post-exilic usage.[14]

The Israelites are the ethnic stock from which modern Jews and Samaritans originally trace their ancestry.[15][16][17][18][19][20] Modern Jews are named after and also descended from the southern Israelite Kingdom of Judah,[8][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] particularly the tribes of Judah, Benjamin and partially Levi.

Finally, in Judaism, the term "Israelite" is, broadly speaking, used to refer to a lay member of the Jewish ethnoreligious group, as opposed to the priestly orders of Kohanim and Levites. In texts of Jewish law such as the Mishnah and Gemara, the term יהודי (Yehudi), meaning Jew, is rarely used, and instead the ethnonym ישראלי (Yisraeli), or Israelite, is widely used to refer to Jews. Samaritans commonly refer to themselves and to Jews collectively as Israelites, and they describe themselves as the Israelite Samaritans.[31][32]

Contents

1 Etymology

2 Terminology

3 Historical Israelites

4 Biblical Israelites

5 Genetics

6 See also

7 References

8 Bibliography

Etymology

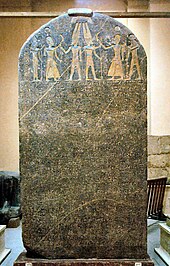

The Merneptah stele. While alternative translations exist, the majority of biblical archaeologists translate a set of hieroglyphs as Israel, representing the first instance of the name Israel in the historical record.

The term Israelite is the English name for the descendants of the biblical patriarch Jacob in ancient times, which is derived from the Greek Ισραηλίτες,[33] which was used to translate the Biblical Hebrew term b'nei yisrael, יִשְׂרָאֵל as either "sons of Israel" or "children of Israel".[34]

The name Israel first appears in the Hebrew Bible in Genesis 32:29. It refers to the renaming of Jacob, who, according to the Bible, wrestled with an angel, who gave him a blessing and renamed him Israel because he had "striven with God and with men, and have prevailed". The Hebrew Bible etymologizes the name as from yisra "to prevail over" or "to struggle/wrestle with", and el, "God, the divine".[35][36]

The name Israel first appears in non-biblical sources c. 1209 BCE, in an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah. The inscription is very brief and says simply: "Israel is laid waste and his seed is not" (see below). The inscription refers to a people, not to an individual or a nation-state.[37]

Terminology

In modern Hebrew, b'nei yisrael ("children of Israel") can denote the Jewish people at any time in history; it is typically used to emphasize Jewish ethnic identity. From the period of the Mishna (but probably used before that period) the term Yisrael ("an Israel") acquired an additional narrower meaning of Jews of legitimate birth other than Levites and Aaronite priests (kohanim). In modern Hebrew this contrasts with the term Yisraeli (English "Israeli"), a citizen of the modern State of Israel, regardless of religion or ethnicity.

The term Hebrew has Eber as an eponymous ancestor. It is used synonymously with "Israelites", or as an ethnolinguistic term for historical speakers of the Hebrew language in general.

The Greek term Ioudaioi (Jews) was an exonym originally referring to members of the Tribe of Judah, which formed the nucleus of the kingdom of Judah, and was later adopted as a self-designation by people in the diaspora who identified themselves as loyal to the God of Israel and the Temple in Jerusalem.[38][39][40][41]

The Samaritans, who claim descent from the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh (plus Levi through Aaron for kohens), are named after the Israelite Kingdom of Samaria, but until modern times many Jewish authorities contested their claimed lineage, deeming them to have been conquered foreigners who were settled in the Land of Israel by the Assyrians, as was the typical Assyrian policy to obliterate national identities. Today, Jews and Samaritans both recognize each other as communities with an authentic Israelite origin.[42]

The terms "Jews" and "Samaritans" largely replaced the title "Children of Israel"[43] as the commonly used ethnonym for each respective community.

Historical Israelites

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Israel |

|

Ancient Israel and Judah |

|

Second Temple period (530 BCE–70 CE) |

|

Middle Ages (70–1517) |

|

Modern history (1517–1948) |

|

State of Israel (1948–present) |

|

History of the Land of Israel by topic |

|

Related |

|

Several theories exist proposing the origins of the Israelites in raiding groups, infiltrating nomads or emerging from indigenous Canaanites driven from the wealthier urban areas by poverty to seek their fortunes in the highland.[44] Various, ethnically distinct groups of itinerant nomads such as the Habiru and Shasu recorded in Egyptian texts as active in Edom and Canaan could have been related to the later Israelites, which does not exclude the possibility that the majority may have had their origins in Canaan proper. The name Yahweh, the god of the later Israelites, may indicate connections with the region of Mount Seir in Edom.[45]

The prevailing academic opinion today is that the Israelites were a mixture of peoples predominantly indigenous to Canaan, although an Egyptian matrix of peoples may also have played a role in their ethnogenesis,[46][47][48] with an ethnic composition similar to that in Ammon, Edom and Moab,[47] and including Hapiru and Šośu.[49] The defining feature which marked them off from the surrounding societies was a staunch egalitarian organisation focused on Yahweh worship, rather than mere kinship.[47]

The language of the Canaanites may perhaps be best described as an "archaic form of Hebrew, standing in much the same relationship to the Hebrew of the Old Testament as does the language of Chaucer to modern English." The Canaanites were also the first people, as far as is known, to have used an alphabet.[50]

The name Israel first appears c. 1209 BCE, at the end of the Late Bronze Age and the very beginning of the period archaeologists and historians call Iron Age I, on the Merneptah Stele raised by the Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah. The inscription is very brief:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Plundered is Canaan with every evil,

Carried off is Ashkelon,

Seized upon is Gezer,

Yenocam is made as that which does not exist

Israel lies fallow, it has no seed;

Ḫurru has become a widow because of Egypt.[45]

As distinct from the cities named (Ashkelon, Gezer, Yenoam) which are written with a toponymic marker, Israel is written hieroglyphically with a demonymic determinative indicating that the reference is to a human group, variously located in central Palestine[45] or the highlands of Samaria.[51]

Over the next two hundred years (the period of Iron Age I) the number of highland villages increased from 25 to over 300[9] and the settled population doubled to 40,000.[52] By the 10th century BCE a rudimentary state had emerged in the north-central highlands,[53] and in the 9th century this became a kingdom.[54] Settlement in the southern highlands was minimal from the 12th through the 10th centuries BCE, but a state began to emerge there in the 9th century,[55] and from 850 BCE onwards a series of inscriptions are evidence of a kingdom which its neighbours refer to as the "House of David."[56]

After the destruction of the Israelite kingdoms of Samaria and Judah in 720 and 586 BCE respectively,[57][58] the concepts of Jew and Samaritan gradually replaced Judahite and Israelite. When the Jews returned from the Babylonian captivity, the Hasmonean kingdom was established[dubious ] in present-day Israel, consisting of three regions which were Judea, Samaria, and the Galilee. In the pre-exilic First Temple Period the political power of Judea was concentrated within the tribe of Judah, Samaria was dominated by the tribe of Ephraim and the House of Joseph, while the Galilee was associated with the tribe of Naphtali, the most eminent tribe of northern Israel.[59][60] At the time of the Kingdom of Samaria, the Galilee was populated by northern tribes of Israel, but following the Babylonian exile the region became Jewish. During the Second Temple period relations between the Jews and Samaritans remained tense. In 120 BCE the Hasmonean king Yohanan Hyrcanos I destroyed the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim, due to the resentment between the two groups over a disagreement of whether Mount Moriah in Jerusalem or Mount Gerizim in Shechem was the actual site of the Aqedah, and the chosen place for the Holy Temple, a source of contention that had been growing since the two houses of the former united monarchy first split asunder in 930 BCE and which had finally exploded into warfare.[61][62][dubious ] 190 years after the destruction of the Samaritan Temple and the surrounding area of Shechem, the Roman general and future emperor Vespasian launched a military campaign to crush the Jewish revolt of 66 CE, which resulted in the destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE by his son Titus, and the subsequent exile of Jews from Judea and the Galilee in 135 CE following the Bar Kochba revolt.[63][64]

Biblical Israelites

Map of the Holy Land, Pietro Vesconte, 1321, showing the allotments of the tribes of Israel. Described by Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld as "the first non-Ptolemaic map of a definite country"[65]

Model of the Mishkan constructed under the auspices of Moses, in Timna Park, Israel

The Israelite story begins with some of the culture heroes of the Jewish people, the Patriarchs. The Torah traces the Israelites to the patriarch Jacob, grandson of Abraham, who was renamed Israel after a mysterious incident in which he wrestles all night with God or an angel. Jacob's twelve sons (in order of birth), Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Joseph and Benjamin, become the ancestors of twelve tribes, with the exception of Joseph, whose two sons Mannasseh and Ephraim, who were adopted by Jacob, become tribal eponyms (Genesis 48).[66]

The mothers of Jacob's sons are:

Leah: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulun

Rachel: Joseph (Ephraim and Menasseh), Benjamin

Bilhah (Rachel's maid): Dan, Naphtali

Zilpah (Leah's maid): Gad, Asher (Genesis 35:22–26)[66]

Jacob and his sons are forced by famine to go down into Egypt, although Joseph was already there, as he had been sold into slavery while young. When they arrive they and their families are 70 in number, but within four generations they have increased to 600,000 men of fighting age, and the Pharaoh of Egypt, alarmed, first enslaves them and then orders the death of all male Hebrew children. A woman from the tribe of Levi hides her child, places him in a woven basket, and sends him down the Nile river. He is named Mosheh, or Moses, by the Egyptians who find him. Being a Hebrew baby, they award a Hebrew woman the task of raising him, the mother of Moses volunteers, and the child and his mother are reunited.[67][68]

At the age of forty Moses kills an Egyptian, after he sees him beating a Hebrew to death, and escapes as a fugitive into the Sinai desert, where he is taken in by the Midianites and marries Zipporah, the daughter of the Midianite priest Jethro. When he is eighty years old, Moses is tending a herd of sheep in solitude on Mount Sinai when he sees a desert shrub that is burning but is not consumed. The God of Israel calls to Moses from the fire and reveals his name, Yahweh (from the Hebrew root word 'HWH' meaning to exist), and tells Moses that he is being sent to Pharaoh to bring the people of Israel out of Egypt.[69]

Yahweh tells Moses that if Pharaoh refuses to let the Hebrews go to say to Pharaoh "Thus says Yahweh: Israel is my son, my first-born and I have said to you: Let my son go, that he may serve me, and you have refused to let him go. Behold, I will slay your son, your first-born". Moses returns to Egypt and tells Pharaoh that he must let the Hebrew slaves go free. Pharaoh refuses and Yahweh strikes the Egyptians with a series of horrific plagues, wonders, and catastrophes, after which Pharaoh relents and banishes the Hebrews from Egypt. Moses leads the Israelites out of bondage[70] toward the Red Sea, but Pharaoh changes his mind and arises to massacre the fleeing Hebrews. Pharaoh finds them by the sea shore and attempts to drive them into the ocean with his chariots and drown them.[71]

Yahweh causes the Red Sea to part and the Hebrews pass through on dry land into the Sinai. After the Israelites escape from the midst of the sea, Yahweh causes the ocean to close back in on the pursuing Egyptian army, drowning them to death. In the desert Yahweh feeds them with manna that accumulates on the ground with the morning dew. They are led by a column of cloud, which ignites at night and becomes a pillar of fire to illuminate the way, southward through the desert until they come to Mount Sinai. The twelve tribes of Israel encamp around the mountain, and on the third day Mount Sinai begins to smolder, then catches fire, and Yahweh speaks the Ten Commandments from the midst of the fire to all the Israelites, from the top of the mountain.[72]

Moses ascends biblical Mount Sinai and fasts for forty days while he writes down the Torah as Yahweh dictates, beginning with Bereshith and the creation of the universe and earth.[73][74] He is shown the design of the Mishkan and the Ark of the Covenant, which Bezalel is given the task of building. Moses descends from the mountain forty days later with the Sefer Torah he wrote, and with two rectangular lapis lazuli[75] tablets, into which Yahweh had carved the Ten Commandments in Paleo–Hebrew. In his absence, Aaron has constructed an image of Yahweh,[76] depicting him as a young Golden Calf, and has presented it to the Israelites, declaring "Behold O Israel, this is your god who brought you out of the land of Egypt". Moses smashes the two tablets and grinds the golden calf into dust, then throws the dust into a stream of water flowing out of Mount Sinai, and forces the Israelites to drink from it.[77]

Map of the twelve tribes of Israel (before the move of Dan to the north), based on the Book of Joshua

Moses ascends Mount Sinai for a second time and Yahweh passes before him and says: 'Yahweh, Yahweh, a god of compassion, and showing favor, slow to anger, and great in kindness and in truth, who shows kindness to the thousandth generation, forgiving wrongdoing and injustice and wickedness, but will by no means clear the guilty, causing the consequences of the parent's wrongdoing to befall their children, and their children's children, to the third and fourth generation'[78] Moses then fasts for another forty days while Yahweh carves the Ten Commandments into a second set of stone tablets. After the tablets are completed, light emanates from the face of Moses for the rest of his life, causing him to wear a veil so he does not frighten people.[79]

Moses descends Mount Sinai and the Israelites agree to be the chosen people of Yahweh and follow all the laws of the Torah. Moses prophesies if they forsake the Torah, Yahweh will exile them for the total number of years they did not observe the shmita.[80] Bezael constructs the Ark of the Covenant and the Mishkan, where the presence of Yahweh dwells on earth in the Holy of Holies, above the Ark of the Covenant, which houses the Ten Commandments. Moses sends spies to scout out the Land of Canaan, and the Israelites are commanded to go up and conquer the land, but they refuse, due to their fear of warfare and violence. In response, Yahweh condemns the entire generation, including Moses, who is condemned for striking the rock at Meribah, to exile and death in the Sinai desert.[81]

Before Moses dies he gives a speech to the Israelites where he paraphrases a summary of the mizwoth given to them by Yahweh, and recites a prophetic song called the Ha'azinu. Moses prophesies that if the Israelites disobey the Torah, Yahweh will cause a global exile in addition to the minor one prophesied earlier at Mount Sinai, but at the end of days Yahweh will gather them back to Israel from among the nations when they turn back to the Torah with zeal.[82] The events of the Israelite exodus and their sojourn in the Sinai are memorialized in the Jewish and Samaritan festivals of Passover and Sukkoth, and the giving of the Torah in the Jewish celebration of Shavuoth.[66][83]

Forty years after the Exodus, following the death of the generation of Moses, a new generation, led by Joshua, enters Canaan and takes possession of the land in accordance with the promise made to Abraham by Yahweh. Land is allocated to the tribes by lottery. Eventually the Israelites ask for a king, and Yahweh gives them Saul. David, the youngest (divinely favored) son of Jesse of Bethlehem would succeed Saul. Under David the Israelites establish the united monarchy, and under David's son Solomon they construct the Holy Temple in Jerusalem, using the 400-year-old materials of the Mishkan, where Yahweh continues to tabernacle himself among them. On the death of Solomon and reign of his son, Rehoboam, the kingdom is divided in two.[84]

The kings of the northern Kingdom of Samaria are uniformly bad, permitting the worship of other gods and failing to enforce the worship of Yahweh alone, and so Yahweh eventually allows them to be conquered and dispersed among the peoples of the earth; and strangers rule over their remnant in the northern land. In Judah some kings are good and enforce the worship of Yahweh alone, but many are bad and permit other gods, even in the Holy Temple itself, and at length Yahweh allows Judah to fall to her enemies, the people taken into captivity in Babylon, the land left empty and desolate, and the Holy Temple itself destroyed.[66][85]

Yet despite these events Yahweh does not forget his people, but sends Cyrus, king of Persia to deliver them from bondage. The Israelites are allowed to return to Judah and Benjamin, the Holy Temple is rebuilt, the priestly orders restored, and the service of sacrifice resumed. Through the offices of the sage Ezra, Israel is constituted as a holy nation, bound by the Torah and holding itself apart from all other peoples.[66][86]

Genetics

According to the bible Abraham came from Ur of the Chaldeans[87] and the Israelites are descended from the Chaldaeans.[88]

Chaldea was a region of ancient Babylonia in what is now southeastern Iraq, the Chaldeans were a group of people who spoke Semitic languages related to Aramic.[89]

The study of Al-Zahery suggests the eastern side of fertile crescent as the homeland of the Y-chromosome haplogroup J, furthermore J(xM172) seems to have had its center in Iraq.[90]

In 2000, M. Hammer, et al. conducted a study on 1371 men and definitively established that part of the paternal gene pool of Jewish communities in Europe, North Africa and Middle East came from a common Middle East ancestral population.[91]

In another study (Nebel) noted; "In comparison with data available from other relevant populations in the region, Jews were found to be much more closely related to groups in the north of the Fertile Crescent (Kurds, Turks, and Armenians) than to their Arab neighbors."[92]

See also

- Biblical archaeology

- Groups claiming affiliation with Israelites

- Lachish relief

- Masoretic Text

- Samaritan Pentateuch

- Tribal allotments of Israel

- Who is a Jew?

References

^ "Israelite". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

^ Finkelstein, Israel. "Ethnicity and origin of the Iron I settlers in the Highlands of Canaan: Can the real Israel stand up?." The Biblical archaeologist 59.4 (1996): 198–212.

^ Finkelstein, Israel. The archaeology of the Israelite settlement. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988.

^ Finkelstein, Israel, and Nadav Na'aman, eds. From nomadism to monarchy: archaeological and historical aspects of early Israel. Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1994.

^ Finkelstein, Israel. "The archaeology of the United Monarchy: an alternative view." Levant 28.1 (1996): 177–87.

^ Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster, 2002.

^ Dever, William (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans. pp. 98–99. ISBN 3-927120-37-5.After a century of exhaustive investigation, all respectable archaeologists have given up hope of recovering any context that would make Abraham, Isaac, or Jacob credible "historical figures" [...] archaeological investigation of Moses and the Exodus has similarly been discarded as a fruitless pursuit.

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Tubb 1998, pp. 13–14

^ ab McNutt 1999, p. 47.

^ K. L. Noll, Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction, A&C Black, 2001 p. 164: "It would seem that, in the eyes of Merneptah's artisans, Israel was a Canaanite group indistinguishable from all other Canaanite groups." "It is likely that Merneptah's Israel was a group of Canaanites located in the Jezreel Valley."

^ Tubb, 1998. pp. 13–14

^ Mark Smith in "The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities of Ancient Israel" states "Despite the long regnant model that the Canaanites and Israelites were people of fundamentally different culture, archaeological data now casts doubt on this view. The material culture of the region exhibits numerous common points between Israelites and Canaanites in the Iron I period (c. 1200–1000 BCE). The record would suggest that the Israelite culture largely overlapped with and derived from Canaanite culture... In short, Israelite culture was largely Canaanite in nature. Given the information available, one cannot maintain a radical cultural separation between Canaanites and Israelites for the Iron I period." (pp. 6–7). Smith, Mark (2002) "The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities of Ancient Israel" (Eerdman's)

^ Rendsberg, Gary (2008). "Israel without the Bible". In Frederick E. Greenspahn. The Hebrew Bible: New Insights and Scholarship. NYU Press, pp. 3–5

^ Robert L.Cate, "Israelite", in Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard, Mercer Dictionary of the Bible, Mercer University Press, 1990 p. 420.

^ Ostrer, Harry (2012). Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People. Oxford University Press (published May 8, 2012). ISBN 978-0195379617.

^ Eisenberg, Ronald (2013). Dictionary of Jewish Terms: A Guide to the Language of Judaism. Schreiber Publishing (published November 23, 2013). p. 431.

^ Gubkin, Liora (2007). You Shall Tell Your Children: Holocaust Memory in American Passover Ritual. Rutgers University Press (published December 31, 2007). p. 190. ISBN 978-0813541938.

^ "Reconstruction of Patrilineages and Matrilineages of Samaritans and Other Israeli Populations From Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation" (PDF). (855 KB), Hum Mutat 24:248–260, 2004.

^ Yohanan Aharoni, Michael Avi-Yonah, Anson F. Rainey, Ze'ev Safrai, The Macmillan Bible Atlas, 3rd Edition, Macmillan Publishing: New York, 1993, p. 115. A posthumous publication of the work of Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni and Michael Avi-Yonah, in collaboration with Anson F. Rainey and Ze'ev Safrai.

^ The Samaritan Update Retrieved 1 January 2017.

^ Ann E. Killebrew, Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity. An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines and Early Israel 1300–1100 B.C.E. (Archaeology and Biblical Studies), Society of Biblical Literature, 2005

^ Schama, Simon (18 March 2014). The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words 1000 BC–1492 AD. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-233944-7.

^ * "In the broader sense of the term, a Jew is any person belonging to the worldwide group that constitutes, through descent or conversion, a continuation of the ancient Jewish people, who were themselves the descendants of the Hebrews of the Old Testament."

- "The Jewish people as a whole, initially called Hebrews (ʿIvrim), were known as Israelites (Yisreʾelim) from the time of their entrance into the Holy Land to the end of the Babylonian Exile (538 BC)."

Jew at Encyclopædia Britannica

^ "Israelite, in the broadest sense, a Jew, or a descendant of the Jewish patriarch Jacob"

Israelite at Encyclopædia Britannica

^ "Hebrew, any member of an ancient northern Semitic people that were the ancestors of the Jews." Hebrew (People) at Encyclopædia Britannica

^ Ostrer, Harry (19 April 2012). Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-970205-3.

^ Brenner, Michael (13 June 2010). A Short History of the Jews. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-14351-X.

^ Scheindlin, Raymond P. (1998). A Short History of the Jewish People: From Legendary Times to Modern Statehood. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513941-9.

^ Adams, Hannah (1840). The History of the Jews: From the Destruction of Jerusalem to the Present Time. London Society House.

^ Diamond, Jared (1993). "Who are the Jews?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2010. Natural History 102:11 (November 1993): 12–19.

^ Yesaahq ben 'Aamraam. Samaritan Exegesis: A Compilation Of Writings From The Samaritans. 2013.

ISBN 1482770814. Benyamim Tsedaka, at 1:24

^ John Bowman. Samaritan Documents Relating to Their History, Religion and Life (Pittsburgh Original Texts and Translations Series No. 2). 1977.

ISBN 0915138271

^ Strong's Exhaustive Concordance G2474

^ Brown Drivers Briggs H3478

^ Scherman, Rabbi Nosson (editor), The Chumash, The Artscroll Series, Mesorah Publications, LTD, 2006, pp. 176–77

^ Kaplan, Aryeh, "Jewish Meditation", Schocken Books, New York, 1985, p. 125

^ Frederick E. Greenspahn (2008). The Hebrew Bible: New Insights and Scholarship. NYU Press. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-0-8147-3187-1.

^ Caroline Johnson Hodge,If Sons, Then Heirs: A Study of Kinship and Ethnicity in the Letters of Paul, Oxford University Press, 2007 pp. 52–55.

^ Markus Cromhout,Jesus and Identity: Reconstructing Judean Ethnicity in Q, James Clarke & Co, 2015 pp. 121ff.

^ Daniel Lynwood Smith,Into the World of the New Testament: Greco-Roman and Jewish Texts and Contexts, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015 p. 124.

^ Stephen Sharot,Comparative Perspectives on Judaisms and Jewish Identities, Wayne State University Press 2011 p. 146.

^ "Homepage of A.B Institute of Samaritan Studies". Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Settings of silver: an introduction to Judaism, Stephen M. Wylen, Paulist Press, 2000,

ISBN 0-8091-3960-X, p. 59

^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed, Simon and Schuster 2002, p. 104.

^ abc K. van der Toorn,Family Religion in Babylonia, Ugarit and Israel: Continuity and Changes in the Forms of Religious Life, BRILL 1996 pp. 181, 282.

^ Alan Mittleman, "Judaism: Covenant, Pluralism and Piety", in Bryan S. Turner (ed.) The New Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Religion, John Wiley & Sons, 2010 pp. 340–63, 346.

^ abc Norman Gottwald, Tribes of Yahweh: A Sociology of the Religion of Liberated Israel, 1250–1050 BCE, A&C Black, 1999 p. 433, cf. 455–56

^ Richard A. Gabriel, The Military History of Ancient Israel. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003 p. 63: The ethnically mixed character of the Israelites is reflected even more clearly in the foreign names of the group's leadership. Moses himself, of course, has an Egyptian name. But so do Hophni, Phinehas, Hur, and Merari, the son of Levi.

^ Stefan Paas, Creation and Judgement: Creation Texts in Some Eighth Century Prophets. Brill, 2003 pp. 110–21, 144.

^ "Canaan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Grabbe 2008, p. 75

^ McNutt 1999, p. 70.

^ Joffe pp. 440ff.

^ Davies, 1992, pp. 63–64.

^ Joffe pp. 448–49.

^ Joffe p. 450.

^ Finkelstein & Silberman 2001, The Bible Unearthed p. 221.

^ Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. T&T Clark International. p. 28. ISBN 0-567-08998-3.

^ Sefer Devariam Pereq לד, ב; Deuteronomy 34, 2, Sefer Yehoshua Pereq כ, ז; Joshua 20, 7, Sefer Yehoshua Pereq כא, לב; Joshua 21, 32, Sefer Melakhim Beth Pereq טו, כט; Second Kings 15, 29, Sefer Devrei Ha Yamim Aleph Pereq ו, סא; First Chronicles 6, 76

^ See File:12 Tribes of Israel Map.svg

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2014.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Y. Magen. "The Gathering at the President's House". Israel Antiquities Authority. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.7.2. Josephus, War of the Jews II.8.11, II.13.7, II.14.4, II.14.5

^ "The Diaspora". Jewish Virtual Library.; "The Bar-Kokhba Revolt". Jewish Virtual Library.

^ Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1889). Facsimile-atlas to the Early History of Cartography: With Reproductions of the Most Important Maps Printed in the XV and XVI Centuries. Kraus. pp. 51, 64.

^ abcde The Jews in the time of Jesus: an introduction p. 18 Stephen M. Wylen, Paulist Press, 1996, 215 pages, pp. 18–20

^ Bereshith, Genesis

^ Shemoth; Exodus 1 and 2

^ Shemoth; Exodus 3 and 4

^ English translation of the papyrus. A translation also in R. B. Parkinson, The Tale of Sinuhe and Other Ancient Egyptian Poems. Oxford World's Classics, 1999.

^ Shemoth; Exodus 5 through 15

^ Shemoth; Exodus 15, 19, and 20

^ Bereshith; Genesis 1

^ The Hidden Face of God: Science Reveals the Ultimate Truth by Gerald L. Schroeder PhD (May 9, 2002)

^ Shemoth; Exodus 24

^ Tehillim; Psalms 106, 19–20

^ Shemoth; Exodus 21 through 32

^ Shemoth; Exodus, 34, 6–7

^ Shemoth; Exodus 34

^ Wayiqra; Leviticus 26

^ Shemoth; Exodus 35 through 40, Wayiqra; Leviticus, Bamidhbar; Numbers, Devariam; Deuteronomy

^ Devariam; Deuteronomy 28 and 29 and 30

^ Devariam; Deuteronomy

^ Yehoshua; Joshua, Shoftim; Judges, Shmuel; Samuel, Melakhim; Kings

^ Melakhim; Kings, Divrei HaYamim; Chronicles

^ Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah

^ Genesis 11:31

^ Judith 5:6

^ World Book Encyclopedia. Chaldea. John A. Brinkman. Chicago. World Book, Inc. 2006

^ N. Al-Zahery et al. "Y-chromosome and mtDNA polymorphisms in Iraq, a crossroad of the early human dispersal and of post-Neolithic migrations" (2003)" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-12-10. https://www.familytreedna.com/sign-in?ReturnUrl=%2Fpdf%2FAl_Zahery.pdf

^ Hammer MF, Redd AJ, Wood ET, et al. (June 2000). "Jewish and Middle Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (12): 6769–6774. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.6769H. doi:10.1073/pnas.100115997. PMC 18733.

PMID 10801975.

^ Nebel, Almut; Filon, Dvora; Brinkmann, Bernd; Majumder, Partha P.; Faerman, Marina; Oppenheim, Ariella (November 2001). "The Y Chromosome Pool of Jews as Part of the Genetic Landscape of the Middle East". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (5): 1095–112. doi:10.1086/324070. PMC 1274378 Freely accessible.

PMID 11573163.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22719-7.

Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume II: From the Exile to the Maccabees. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22720-3.

Albertz, Rainer (2003a). Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-055-4.

Albertz, Rainer; Becking, Bob, eds. (2003b). Yahwism After the Exile: Perspectives on Israelite Religion in the Persian Era. Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 978-90-232-3880-5.

Amit, Yaira; et al., eds. (2006). Essays on Ancient Israel in its Near Eastern Context: A Tribute to Nadav Na'aman. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-128-3.

Avery-Peck, Alan; et al., eds. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Judaism. Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-57718-059-3.

Barstad, Hans M. (2008). History and the Hebrew Bible. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-149809-1.

Becking, Bob, ed. (2001). Only One God? Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84127-199-6.

Becking, Bob. Law as Expression of Religion (Ezra 7–10).

Becking, Bob; Korpel, Marjo Christina Annette, eds. (1999). The Crisis of Israelite Religion: Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic and Post-Exilic Times. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11496-8.

Niehr, Herbert. Religio-Historical Aspects of the Early Post-Exilic Period.

Bedford, Peter Ross (2001). Temple Restoration in Early Achaemenid Judah. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11509-5.

Ben-Sasson, H.H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39731-2.

Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1988). Ezra-Nehemiah: A Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-664-22186-7.

Blenkinsopp, Joseph; Lipschits, Oded, eds. (2003). Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-073-6.

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. Bethel in the Neo-Babylonian Period.

Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2009). Judaism, the First Phase: The Place of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Origins of Judaism. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6450-5.

Brett, Mark G. (2002). Ethnicity and the Bible. Brill. ISBN 978-0-391-04126-4.

Bright, John (2000). A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22068-6.

Cahill, Jane M. Jerusalem at the Time of the United Monarchy.

Coogan, Michael D., ed. (1998). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533272-8.

Coote, Robert B.; Whitelam, Keith W. (1986). "The Emergence of Israel: Social Transformation and State Formation Following the Decline in Late Bronze Age Trade". Semeia (37): 107–47.

Davies, Philip R. The Origin of Biblical Israel.

Davies, Philip R. (1992). In Search of Ancient Israel. Sheffield. ISBN 978-1-85075-737-5.

Davies, Philip R. (2009). "The Origin of Biblical Israel". Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 9 (47). Archived from the original on May 28, 2008.

Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-6830-7.

Dever, William (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2126-3.

Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0975-9.

Dever, William (2005). Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2852-1.

Dijkstra, Meindert. El the God of Israel, Israel the People of YHWH: On the Origins of Ancient Israelite Yahwism.

Dijkstra, Meindert. I Have Blessed You by YHWH of Samaria and His Asherah: Texts with Religious Elements from the Soil Archive of Ancient Israel.

Dunn, James D.G; Rogerson, John William, eds. (2003). Eerdmans commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

Edelman, Diana. Ethnicity and Early Israel.

Edelman, Diana, ed. (1995). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Kok Pharos. ISBN 978-90-390-0124-0.

Finkelstein, Neil Asher; Silberman (2001). The Bible Unearthed. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6.

Finkelstein, Israel; Mazar, Amihay; Schmidt, Brian B. (2007). The Quest for the Historical Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-277-0.

Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-85075-657-6.

Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004a). Ancient Canaan and Israel: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537985-3.

Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004b). Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-897-6.

Goodison, Lucy; Morris, Christine (1998). Goddesses in Early Israelite Religion in Ancient Goddesses: The Myths and the Evidence. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-90-04-10410-5.

Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. T&T Clark International. ISBN 978-0-567-04352-8.

Grabbe, Lester L., ed. (2008). Israel in Transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIa (c. 1250–850 B.C.E.). T&T Clark International. ISBN 978-0-567-02726-9.

Greifenhagen, F.V (2002). Egypt on the Pentateuch's ideological map. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-6211-4.

Hesse, Brian; Wapnish, Paula (1997). "Can Pig Remains Be Used for Ethnic Diagnosis in the Ancient Near East?". In Silberman, Neil Asher; Small, David B. The Archaeology of Israel: Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 1-85075-650-3.

Joffe, Alexander H. (2006). The Rise of Secondary States in the Iron Age Levant. University of Arizona Press.

Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-097-4.

King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). Life in Biblical Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22148-3.

Kottsieper, Ingo. And They Did Not Care to Speak Yehudit.

Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 C. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5.

Lehman, Gunnar. The United Monarchy in the Countryside.

Lemaire, Andre. Nabonidus in Arabia and Judea During the Neo-Babylonian Period.

Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22727-2.

Levy, Thomas E. (1998). The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8264-6996-0.

LaBianca, Øystein S.; Younker, Randall W. The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (c. 1400–500 CE).

Lipschits, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-095-8.

Lipschits, Oded; et al., eds. (2006). Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-130-6.

Lipschits, Oded; Vanderhooft, David. Yehud Stamp Impressions in the Fourth Century B.C.E.

Mazar, Amihay. The Divided Monarchy: Comments on Some Archaeological Issues.

Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22614-2.

Mays, James Luther; et al., eds. (1995). Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clarke. ISBN 978-0-567-29289-6.

Miller, J. Maxwell. The Middle East and Archaeology.

McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22265-9.

Merrill, Eugene H. (1995). "The Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Transition and the Emergence of Israel". Bibliotheca Sacra. 152 (606): 145–62.

Middlemas, Jill Anne (2005). The Troubles of Templeless Judah. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928386-6.

Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-21262-X.

Miller, Robert D. (2005). Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the 12th and 11th Centuries B.C. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0988-9.

Murphy, Frederick J. R. Second Temple Judaism.

Nodet, Étienne (1999) [Editions du Cerf 1997]. A Search for the Origins of Judaism: From Joshua to the Mishnah. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-85075-445-9.

Pitkänen, Pekka (2004). "Ethnicity, Assimilation and the Israelite Settlement" (PDF). Tyndale Bulletin. 55 (2): 161–82. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2011.

Rogerson, John William. Deuteronomy.

Silberman, Neil Asher; Small, David B., eds. (1997). The Archaeology of Israel: Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-85075-650-7.

Smith, Mark S. (2001). Untold Stories: The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century. Hendrickson Publishers.

Smith, Mark S.; Miller, Patrick D. (2002) [Harper & Row 1990]. The Early History of God. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3972-5.

Soggin, Michael J. (1998). An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah. Paideia. ISBN 978-0-334-02788-1.

Stager, Lawrence E. Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel.

Thompson, Thomas L. (1992). Early History of the Israelite People. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09483-3.

Van der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10410-5.

Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2d ed.). Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11119-6.

Tubb, Jonathan N. (1998). Canaanites. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3108-X.

Vaughn, Andrew G.; Killebrew, Ann E., eds. (1992). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Sheffield. ISBN 978-1-58983-066-0.

Wylen, Stephen M. (1996). The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3610-0.

Zevit, Ziony (2001). The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-6339-5.