Stele (biology)

In a vascular plant, the stele is the central part of the root or stem[1] containing the tissues derived from the procambium. These include vascular tissue, in some cases ground tissue (pith) and a pericycle, which, if present, defines the outermost boundary of the stele. Outside the stele lies the endodermis, which is the innermost cell layer of the cortex.

The concept of the stele was developed in the late 19th century by French botanists P. E. L. van Tieghem and H. Doultion as a model for understanding the relationship between the shoot and root, and for discussing the evolution of vascular plant morphology.[2] Now, at the beginning of the 21st century, plant molecular biologists are coming to understand the genetics and developmental pathways that govern tissue patterns in the stele.[citation needed] Moreover, physiologists are examining how the anatomy (sizes and shapes) of different steles affect the function of organs.

Contents

1 Protostele

2 Siphonostele

3 See also

4 Citations

5 References

Protostele

The earliest vascular plants had stems with a central core of vascular tissue.[3][4] This consisted of a cylindrical strand of xylem, surrounded by a region of phloem. Around the vascular tissue there might have been an endodermis that regulated the flow of water into and out of the vascular system. Such an arrangement is termed a protostele.[5]

There are usually three basic types of protostele:

haplostele – consisting of a cylindrical core of xylem surrounded by a ring of phloem. An endodermis generally surrounds the stele. A centrarch (protoxylem in the center of a metaxylem cylinder) haplostele is prevalent in members of the rhyniophyte grade, such as Rhynia.[6]

actinostele – a variation of the protostele in which the core is lobed or fluted. This stele is found in many species of club moss (Lycopodium and related genera). Actinosteles are typically exarch (protoxylem external to the metaxylem) and consist of several to many patches of protoxylem at the tips of the lobes of the metaxylem. Exarch protosteles are a defining characteristic of the lycophyte lineage.

plectostele – a protostele in which plate-like regions of xylem appear in transverse section surrounded by phloem tissue. In fact, these discrete plates are interconnected in longitudinal section. Some modern club mosses have plectosteles in their stems. The plectostele may be derived from the actinostele.

Siphonostele

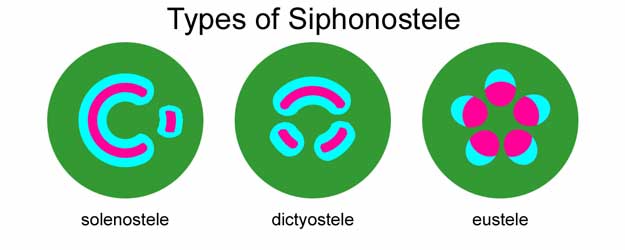

Siphonosteles have a region of ground tissue called the pith internal to xylem. The vascular strand comprises a cylinder surrounding the pith. Siphonosteles often have interruptions in the vascular strand where leaves (typically megaphylls) originate (called leaf gaps).

Siphonosteles can be ectophloic (phloem present only external to the xylem) or they can be amphiphloic (with phloem both external and internal to the xylem). Among living plants, many ferns and some Asterid flowering plants have an amphiphloic stele.

An amphiphloic siphonostele can be called a:

solenostele – if the cylinder of vascular tissue contains no more than one leaf gap in any transverse section (i.e. has non-overlapping leaf gaps). This type of stele is primarily found in fern stems today.

dictyostele – if multiple gaps in the vascular cylinder exist in any one transverse section. The numerous leaf gaps and leaf traces give a dictyostele the appearance of many isolated islands of xylem surrounded by phloem. Each of the apparently isolated units of a dictyostele can be called a meristele. Among living plants, this type of stele is found only in the stems of ferns.

Most seed plant stems possess a vascular arrangement which has been interpreted as a derived siphonostele, and is called a

eustele – in this arrangement, the primary vascular tissue consists of vascular bundles, usually in one or two rings around the pith.[7] In addition to being found in stems, the eustele appears in the roots of monocot flowering plants. The vascular bundles in a eustele can be collateral (with the phloem on only one side of the xylem) or bicollateral (with phloem on both sides of the xylem, as in some Solanaceae).

There is also a variant of the eustele found in monocots like maize and rye. The variation has numerous scattered bundles in the stem and is called an atactostele (characterestic of monocot stem). However, it is really just a variant of the eustele.[7][8]

See also

- Vascular tissue

- Vascular bundle

Citations

^ Foster & Gifford (1974), p. 58.

^ Gifford & Foster (1988), p. 42.

^ Bold, Alexopoulos & Delevoryas (1987), p. 320.

^ Stewart & Rothwell (1993), pp. 85–89.

^ Gifford & Foster (1988), p. 44.

^ Arnold (1947), pp. 66–68.

^ ab Bold, Alexopoulos & Delevoryas (1987), p. 322.

^ Gifford & Foster (1988), p. 45.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Arnold, Chester A. (1947). An Introduction to Paleobotany (1st ed.). New York and London: McGraw-Hill Book Company..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Bold, Harold C.; Alexopoulos, Constantine J. & Delevoryas, Theodore (1987). Morphology of Plants and Fungi (5th ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-040839-1.

Foster, A. S. & Gifford, E. M. (1974). Comparative Morphology of Vascular Plants (2nd ed.). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-0712-7.

Gifford, Ernest M. & Foster, Adriance S. (1988). Morphology and Evolution of Vascular Plants (3rd ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-1946-0.

Stewart, Wilson N. & Rothwell, Gar W. (1993). Paleobotany and the Evolution of Plants (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38294-7.