Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων Basileía Rhōmaíōna Imperium Romanum | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 395–1453b | |||||||||

Solidus with the image of Heraclius (r. 610-641), with his son Heraclius Constantine. (see Byzantine insignia) | |||||||||

The empire in AD 555 under Justinian the Great, at its greatest extent since the fall of the Western Roman Empire (its vassals in pink) | |||||||||

| Capital | Constantinoplec (330–1204, 1261–1453) | ||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity (Eastern Orthodox) (tolerated after the Edict of Milan in 313; state religion after 380) | ||||||||

| Government | Republican monarchy[1]Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Notable emperors | |||||||||

• 395–408 | Arcadius | ||||||||

• 527–565 | Justinian I | ||||||||

• 610–641 | Heraclius | ||||||||

• 717–741 | Leo III | ||||||||

• 976–1025 | Basil II | ||||||||

• 1081–1118 | Alexios I Komnenos | ||||||||

• 1259–1282 | Michael VIII Palaiologos | ||||||||

• 1449–1453 | Constantine XI | ||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity to Late Middle Ages | ||||||||

• First division of the Roman Empire (diarchy) | 1 April 286 | ||||||||

• Founding of Constantinople | 11 May 330 | ||||||||

• Final East–West division after the death of Theodosius I | 17 January 395 | ||||||||

• Nominal end of the Western Roman Empire | 25 April 480 | ||||||||

• Fourth Crusade; establishment of the Latin Empire | 12 April 1204 | ||||||||

• Reconquest of Constantinople by Palaiologos | 25 July 1261 | ||||||||

• Fall of Constantinople | 29 May 1453 | ||||||||

• Fall of Trebizond | 15 August 1461 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 457 AD | 16,000,000d | ||||||||

• 565 AD | 19,000,000 | ||||||||

• 775 AD | 7,000,000 | ||||||||

• 1025 AD | 12,000,000 | ||||||||

• 1320 AD | 2,000,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Solidus, histamenon and hyperpyron | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

History of the Byzantine Empire |

|

Preceding |

|

Early period (330–717) |

|

Middle period (717–1204) |

|

Late period (1204–1453) |

|

Timeline |

By topic |

|

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire and Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, which had been founded as Byzantium). It survived the fragmentation and fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD and continued to exist for an additional thousand years until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.[2] During most of its existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in Europe. Both "Byzantine Empire" and "Eastern Roman Empire" are historiographical terms created after the end of the realm; its citizens continued to refer to their empire simply as the Roman Empire (Greek: Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων, tr. Basileia Rhōmaiōn; Latin: Imperium Romanum),[3] or Romania (Ῥωμανία), and to themselves as "Romans".[4]

Several signal events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the period of transition during which the Roman Empire's Greek East and Latin West divided. Constantine I (r. 324–337) reorganised the empire, made Constantinople the new capital, and legalised Christianity. Under Theodosius I (r. 379–395), Christianity became the Empire's official state religion and other religious practices were proscribed. Finally, under the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641), the Empire's military and administration were restructured and adopted Greek for official use instead of Latin.[5] Thus, although the Roman state continued and its traditions were maintained, modern historians distinguish Byzantium from ancient Rome insofar as it was centred on Constantinople, oriented towards Greek rather than Latin culture, and characterised by Orthodox Christianity.[4]

The borders of the empire evolved significantly over its existence, as it went through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), the Empire reached its greatest extent after reconquering much of the historically Roman western Mediterranean coast, including North Africa, Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more centuries. During the reign of Maurice (r. 582–602), the Empire's eastern frontier was expanded and the north stabilised. However, his assassination caused the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, which exhausted the empire's resources and contributed to major territorial losses during the Early Muslim conquests of the seventh century. In a matter of years the empire lost its richest provinces, Egypt and Syria, to the Arabs.[6] During the Macedonian dynasty (10th–11th centuries), the empire again expanded and experienced the two-century long Macedonian Renaissance, which came to an end with the loss of much of Asia Minor to the Seljuk Turks after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. This battle opened the way for the Turks to settle in Anatolia.

The empire recovered again during the Komnenian restoration, such that by the 12th century Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest European city.[7] However, it was delivered a mortal blow during the Fourth Crusade, when Constantinople was sacked in 1204 and the territories that the empire formerly governed were divided into competing Byzantine Greek and Latin realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople in 1261, the Byzantine Empire remained only one of several small rival states in the area for the final two centuries of its existence. Its remaining territories were progressively annexed by the Ottomans over the 14th and 15th century. The Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 finally ended the Byzantine Empire.[8] The last of the imperial Byzantine successor states, the Empire of Trebizond, would be conquered by the Ottomans eight years later in the 1461 Siege of Trebizond.[9]

Contents

1 Nomenclature

2 History

2.1 Early history

2.2 Decentralization of power

2.3 Recentralisation

2.4 Loss of the Western Roman Empire

2.5 Justinian dynasty

2.6 Shrinking borders

2.6.1 Early Heraclian dynasty

2.6.2 The First Arab Siege of Constantinople (674–678) and the theme system

2.6.3 Late Heraclian dynasty

2.6.4 The Second Arab Siege of Constantinople (717–718) and the Isaurian dynasty

2.6.5 Religious dispute over iconoclasm

2.7 Macedonian dynasty and resurgence (867–1025)

2.7.1 Wars against the Arabs

2.7.2 Wars against the Bulgarian Empire

2.7.3 Relations with the Kievan Rus'

2.7.4 Campaigns against Georgia

2.7.5 Apex

2.7.6 Split between Orthodox Christianity and Catholicism (1054)

2.8 Crisis and fragmentation

2.9 Komnenian dynasty and the crusaders

2.9.1 Alexios I and the First Crusade

2.9.2 John II, Manuel I and the Second Crusade

2.9.3 12th-century Renaissance

2.10 Decline and disintegration

2.10.1 Angelid dynasty

2.10.2 Fourth Crusade

2.10.3 Crusader sack of Constantinople (1204)

2.11 Fall

2.11.1 Empire in exile

2.11.2 Reconquest of Constantinople

2.11.3 Rise of the Ottomans and fall of Constantinople

2.12 Political aftermath

3 Government and bureaucracy

3.1 Diplomacy

4 Science, medicine and law

5 Culture

5.1 Religion

5.2 The arts

5.2.1 Art and literature

5.2.2 Music

5.3 Cuisine

5.4 Flags and insignia

5.5 Language

5.6 Recreation

6 Economy

7 Legacy

8 See also

9 Annotations

10 Notes

11 References

11.1 Primary sources

11.2 Secondary sources

12 Further reading

13 External links

13.1 Byzantine studies, resources and bibliography

Nomenclature

The first use of the term "Byzantine" to label the later years of the Roman Empire was in 1557, when the German historian Hieronymus Wolf published his work Corpus Historiæ Byzantinæ, a collection of historical sources. The term comes from "Byzantium", the name of the city of Constantinople before it became Constantine's capital. This older name of the city would rarely be used from this point onward except in historical or poetic contexts. The publication in 1648 of the Byzantine du Louvre (Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae), and in 1680 of Du Cange's Historia Byzantina further popularised the use of "Byzantine" among French authors, such as Montesquieu.[10] However, it was not until the mid-19th century that the term came into general use in the Western world.[11]

The Byzantine Empire was known to its inhabitants as the "Roman Empire", the "Empire of the Romans" (Latin: Imperium Romanum, Imperium Romanorum; Greek: Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων Basileia tōn Rhōmaiōn, Ἀρχὴ τῶν Ῥωμαίων Archē tōn Rhōmaiōn), "Romania" (Latin: Romania; Greek: Ῥωμανία Rhōmania),[n 1] the "Roman Republic" (Latin: Res Publica Romana; Greek: Πολιτεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων Politeia tōn Rhōmaiōn), and also as "Rhōmais" (Greek: Ῥωμαΐς).[14] The inhabitants called themselves Romaioi and even as late as the 19th century Greeks typically referred to Modern Greek as Romaiika "Romaic."[15][16] and followers of the Apostles.[17] After 1204 when the Byzantine Empire was mostly confined to its purely Greek provinces the term 'Hellenes' was used instead.[18]

Although the Byzantine Empire had a multi-ethnic character during most of its history[19] and preserved Romano-Hellenistic traditions,[20] it became identified by its western and northern contemporaries with its increasingly predominant Greek element.[21] The occasional use of the term "Empire of the Greeks" (Latin: Imperium Graecorum) in the West to refer to the Eastern Roman Empire and of the Byzantine Emperor as Imperator Graecorum (Emperor of the Greeks)[22] were also used to separate it from the prestige of the Roman Empire within the new kingdoms of the West.[23] Due to the heartland of the Byzantine Empire being in Greek-speaking areas, Greek was the official language.[24] However, it would be wrong to see Byzantium solely as a Greek empire: other languages, such as Armenian and various Slavic languages, were also widely spoken, especially in the frontier districts.[24]

The authority of the Byzantine emperor as the legitimate Roman emperor was challenged by the coronation of Charlemagne as Imperator Augustus by Pope Leo III in the year 800. Needing Charlemagne's support in his struggle against his enemies in Rome, Leo used the lack of a male occupant of the throne of the Roman Empire at the time to claim that it was vacant and that he could therefore crown a new Emperor himself.[25]

No such distinction existed in the Islamic and Slavic worlds, where the Empire was more straightforwardly seen as the continuation of the Roman Empire. In the Islamic world, the Roman Empire was known primarily as Rûm.[26] The name millet-i Rûm, or "Roman nation," was used by the Ottomans through the 20th century to refer to the former subjects of the Byzantine Empire, that is, the Orthodox Christian community within Ottoman realms.

History

Early history

The Baptism of Constantine painted by Raphael's pupils (1520–1524, fresco, Vatican City, Apostolic Palace); Eusebius of Caesarea records that (as was common among converts of early Christianity) Constantine delayed receiving baptism until shortly before his death[27]

The Roman army succeeded in conquering many territories covering the entire Mediterranean region and coastal regions in southwestern Europe and north Africa. These territories were home to many different cultural groups, both urban populations and rural populations. Generally speaking, the eastern Mediterranean provinces were more urbanised than the western, having previously been united under the Macedonian Empire and Hellenised by the influence of Greek culture.[28]

The West also suffered more heavily from the instability of the 3rd century AD. This distinction between the established Hellenised East and the younger Latinised West persisted and became increasingly important in later centuries, leading to a gradual estrangement of the two worlds.[28]

Decentralization of power

To maintain control and improve administration, various schemes to divide the work of the Roman Emperor by sharing it between individuals were tried between 285 and 324, from 337 to 350, from 364 to 392, and again between 395 and 480. Although the administrative subdivisions varied, they generally involved a division of labour between East and West. Each division was a form of power-sharing (or even job-sharing), for the ultimate imperium was not divisible and therefore the empire remained legally one state—although the co-emperors often saw each other as rivals or enemies.

In 293, emperor Diocletian created a new administrative system (the tetrarchy), to guarantee security in all endangered regions of his Empire. He associated himself with a co-emperor (Augustus), and each co-emperor then adopted a young colleague given the title of Caesar, to share in their rule and eventually to succeed the senior partner. The tetrarchy collapsed, however, in 313 and a few years later Constantine I reunited the two administrative divisions of the Empire as sole Augustus.[29]

Recentralisation

After the death of Theodosius I in 395 the empire was divided. The western part collapsed in the 400s while the eastern part ended with the capture of Constantinople 1453.

The Western Roman Empire

The Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire

Restored section of the Theodosian Walls

In 330, Constantine moved the seat of the Empire to Constantinople, which he founded as a second Rome on the site of Byzantium, a city strategically located on the trade routes between Europe and Asia and between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Constantine introduced important changes into the Empire's military, monetary, civil and religious institutions. As regards his economic policies in particular, he has been accused by certain scholars of "reckless fiscality", but the gold solidus he introduced became a stable currency that transformed the economy and promoted development.[30]

Under Constantine, Christianity did not become the exclusive religion of the state, but enjoyed imperial preference, because the emperor supported it with generous privileges. Constantine established the principle that emperors could not settle questions of doctrine on their own, but should summon instead general ecclesiastical councils for that purpose. His convening of both the Synod of Arles and the First Council of Nicaea indicated his interest in the unity of the Church, and showcased his claim to be its head.[31] The rise of Christianity was briefly interrupted on the accession of the emperor Julian in 361, who made a determined effort to restore polytheism throughout the empire and was thus dubbed "Julian the Apostate" by the Church.[32] However this was reversed when Julian was killed in battle in 363.[33]

Theodosius I (379–395) was the last Emperor to rule both the Eastern and Western halves of the Empire. In 391 and 392 he issued a series of edicts essentially banning pagan religion. Pagan festivals and sacrifices were banned, as was access to all pagan temples and places of worship.[34] The last Olympic Games are believed to have been held in 393.[35] In 395, Theodosius I bequeathed the imperial office jointly to his sons: Arcadius in the East and Honorius in the West, once again dividing Imperial administration. In the 5th century the Eastern part of the empire was largely spared the difficulties faced by the West—due in part to a more established urban culture and greater financial resources, which allowed it to placate invaders with tribute and pay foreign mercenaries. This success allowed Theodosius II to focus on the codification of Roman law and further fortification of the walls of Constantinople, which left the city impervious to most attacks until 1204.[36] Large portions of the Theodosian Walls are preserved to the present day.

To fend off the Huns, Theodosius had to pay an enormous annual tribute to Attila. His successor, Marcian, refused to continue to pay the tribute, but Attila had already diverted his attention to the West. After Attila's death in 453, the Hun Empire collapsed, and many of the remaining Huns were often hired as mercenaries by Constantinople.[37]

Loss of the Western Roman Empire

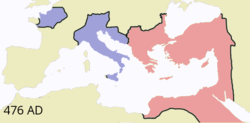

The Western and Eastern Roman Empires by 476

After the fall of Attila, the Eastern Empire enjoyed a period of peace, while the Western Empire deteriorated due to continuing migration and expansion by the Germanic nations (its end is usually dated in 476 when the Germanic Roman general Odoacer deposed the usurper Western Emperor Romulus Augustulus[38]).

In 480 with the death of the Western Emperor Julius Nepos, Eastern Emperor Zeno became sole Emperor of the empire. Odoacer, now ruler of Italy, was nominally Zeno's subordinate but acted with complete autonomy, eventually providing support to a rebellion against the Emperor.[39]

Coins minted during the reign of Anastasius: here a 40 nummi (M) and 5 nummi (E)

Zeno negotiated with the invading Ostrogoths, who had settled in Moesia, convincing the Gothic king Theodoric to depart for Italy as magister militum per Italiam ("commander in chief for Italy") with the aim of deposing Odoacer. By urging Theodoric to conquer Italy, Zeno rid the Eastern Empire of an unruly subordinate (Odoacer) and moved another (Theodoric) further from the heart of the Empire. After Odoacer's defeat in 493, Theodoric ruled Italy de facto, although he was never recognised by the eastern emperors as "king" (rex).[39]

In 491, Anastasius I, an aged civil officer of Roman origin, became Emperor, but it was not until 497 that the forces of the new emperor effectively took the measure of Isaurian resistance.[40] Anastasius revealed himself as an energetic reformer and an able administrator. He introduced a new coinage system of the copper follis, the coin used in most everyday transactions.[41] He also reformed the tax system and permanently abolished the chrysargyron tax. The State Treasury contained the enormous sum of 320,000 lb (150,000 kg) of gold when Anastasius died in 518.[42]

Justinian dynasty

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

The Justinian dynasty was founded by Justin I, who though illiterate, rose through the ranks of the military to become Emperor in 518.[43] He was succeeded by his nephew Justinian I in 527, who may already have exerted effective control during Justin's reign.[44] One of the most important figures of late antiquity and possibly the last Roman emperor to speak Latin as a first language,[45] Justinian's rule constitutes a distinct epoch, marked by the ambitious but only partly realized renovatio imperii, or "restoration of the Empire".[46] His wife Theodora was particularly influential.[47]

In 529, Justinian appointed a ten-man commission chaired by John the Cappadocian to revise Roman law and create a new codification of laws and jurists' extracts, known as the "Corpus Juris Civilis"or the Justinian Code. In 534, the Corpus was updated and, along with the enactments promulgated by Justinian after 534, formed the system of law used for most of the rest of the Byzantine era.[48] The Corpus forms the basis of civil law of many modern states.[49]

The enlargement of the Byzantine Empire's possessions between the rise to power of Justinian (red, 527) and his and Belisarius's death (orange, 565). Belisarius contributed immensely to the expansion of the empire.

In 532, attempting to secure his eastern frontier, Justinian signed a peace treaty with Khosrau I of Persia, agreeing to pay a large annual tribute to the Sassanids. In the same year, he survived a revolt in Constantinople (the Nika riots), which solidified his power but ended with the deaths of a reported 30,000 to 35,000 rioters on his orders.[50] The western conquests began in 533, as Justinian sent his general Belisarius to reclaim the former province of Africa from the Vandals, who had been in control since 429 with their capital at Carthage.[51] Their success came with surprising ease, but it was not until 548 that the major local tribes were subdued.[52] In Ostrogothic Italy, the deaths of Theodoric, his nephew and heir Athalaric, and his daughter Amalasuntha had left her murderer, Theodahad (r. 534–536), on the throne despite his weakened authority.[53]

In 535, a small Byzantine expedition to Sicily met with easy success, but the Goths soon stiffened their resistance, and victory did not come until 540, when Belisarius captured Ravenna, after successful sieges of Naples and Rome.[53] In 535–536, Theodahad sent Pope Agapetus I to Constantinople to request the removal of Byzantine forces from Sicily, Dalmatia, and Italy. Although Agapetus failed in his mission to sign a peace with Justinian, he succeeded in having the Monophysite Patriarch Anthimus I of Constantinople denounced, despite empress Theodora's support and protection.[54]

Empress Theodora and attendants (mosaic from Basilica of San Vitale, 6th century).

The Ostrogoths were soon reunited under the command of King Totila and captured Rome in 546. Belisarius, who had been sent back to Italy in 544, was eventually recalled to Constantinople in 549.[55] The arrival of the Armenian eunuch Narses in Italy (late 551) with an army of 35,000 men marked another shift in Gothic fortunes. Totila was defeated at the Battle of Taginae and his successor, Teia, was defeated at the Battle of Mons Lactarius (October 552). Despite continuing resistance from a few Gothic garrisons and two subsequent invasions by the Franks and Alemanni, the war for the Italian peninsula was at an end.[56] In 551, Athanagild, a noble from Visigothic Hispania, sought Justinian's help in a rebellion against the king, and the emperor dispatched a force under Liberius, a successful military commander. The empire held on to a small slice of the Iberian Peninsula coast until the reign of Heraclius.[57]

In the east, the Roman–Persian Wars continued until 561 when the envoys of Justinian and Khosrau agreed on a 50-year peace.[58] By the mid-550s, Justinian had won victories in most theatres of operation, with the notable exception of the Balkans, which were subjected to repeated incursions from the Slavs and the Gepids. Tribes of Serbs and Croats were later resettled in the northwestern Balkans, during the reign of Heraclius.[59] Justinian called Belisarius out of retirement and defeated the new Hunnish threat. The strengthening of the Danube fleet caused the Kutrigur Huns to withdraw and they agreed to a treaty that allowed safe passage back across the Danube.[60]

Although polytheism had been suppressed by the state since at least the time of Constantine in the 4th century, traditional Greco-Roman culture was still influential in the Eastern empire in the 6th century.[61]Hellenistic philosophy began to be gradually amalgamated into newer Christian philosophy. Philosophers such as John Philoponus drew on neoplatonic ideas in addition to Christian thought and empiricism. Because of active paganism of its professors Justinian closed down the Neoplatonic Academy in 529. Other schools continued in Constantinople, Antioch and Alexandria which were the centers of Justinian's empire.[62] Hymns written by Romanos the Melodist marked the development of the Divine Liturgy, while the architects Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles worked to complete the new Church of the Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, which was designed to replace an older church destroyed during the Nika Revolt. Completed in 537, the Hagia Sophia stands today as one of the major monuments of Byzantine architectural history.[63] During the 6th and 7th centuries, the Empire was struck by a series of epidemics, which greatly devastated the population and contributed to a significant economic decline and a weakening of the Empire.[64]

Follis with Maurice in consular uniform.

The Byzantine Empire in 600 AD during the reign of Emperor Maurice. Half of the Italian peninsula and some part af Spain were lost, but the borders were pushed eastward where Byzantines received some land from the Persians.

After Justinian died in 565, his successor, Justin II, refused to pay the large tribute to the Persians. Meanwhile, the Germanic Lombards invaded Italy; by the end of the century, only a third of Italy was in Byzantine hands. Justin's successor, Tiberius II, choosing between his enemies, awarded subsidies to the Avars while taking military action against the Persians. Although Tiberius' general, Maurice, led an effective campaign on the eastern frontier, subsidies failed to restrain the Avars. They captured the Balkan fortress of Sirmium in 582, while the Slavs began to make inroads across the Danube.[65]

Maurice, who meanwhile succeeded Tiberius, intervened in a Persian civil war, placed the legitimate Khosrau II back on the throne, and married his daughter to him. Maurice's treaty with his new brother-in-law enlarged the territories of the Empire to the East and allowed the energetic Emperor to focus on the Balkans. By 602, a series of successful Byzantine campaigns had pushed the Avars and Slavs back across the Danube.[65] However, Maurice's refusal to ransom several thousand captives taken by the Avars, and his order to the troops to winter in the Danube, caused his popularity to plummet. A revolt broke out under an officer named Phocas, who marched the troops back to Constantinople; Maurice and his family were murdered while trying to escape.[66]

Shrinking borders

Early Heraclian dynasty

Battle between Heraclius and the Persians. Fresco by Piero della Francesca, c. 1452

After Maurice's murder by Phocas, Khosrau used the pretext to reconquer the Roman province of Mesopotamia.[67] Phocas, an unpopular ruler invariably described in Byzantine sources as a "tyrant", was the target of a number of Senate-led plots. He was eventually deposed in 610 by Heraclius, who sailed to Constantinople from Carthage with an icon affixed to the prow of his ship.[68]

Following the accession of Heraclius, the Sassanid advance pushed deep into the Levant, occupying Damascus and Jerusalem and removing the True Cross to Ctesiphon.[69] The counter-attack launched by Heraclius took on the character of a holy war, and an acheiropoietos image of Christ was carried as a military standard[70] (similarly, when Constantinople was saved from a combined Avar–Sassanid–Slavic siege in 626, the victory was attributed to the icons of the Virgin that were led in procession by Patriarch Sergius about the walls of the city).[71] In this very siege of Constantinople of the year 626, amidst the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, the combined Avar, Sassanid, and Slavic forces unsuccessfully besieged the Byzantine capital between June and July. After this, the Sassanid army was forced to withdraw to Anatolia. The loss came just after news had reached them of yet another Byzantine victory, where Heraclius's brother Theodore scored well against the Persian general Shahin.[72] Following this, Heraclius led an invasion into Sassanid Mesopotamia once again.

The Byzantine Empire in 650 – Because of the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 both Byzantines and Persians exhausted themselves and made them vulnerable for the expansion of the Caliphate. In 650 the Byzantine Empire had lost all of its southern provinces except the Exarchate of Africa to the Caliphate. At the same time the Slavs laid pressure and settled in the Balkans.

The main Sassanid force was destroyed at Nineveh in 627, and in 629 Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony,[73] as he marched into the Sassanid capital of Ctesiphon, where anarchy and civil war reigned as a result of the enduring war. Eventually, the Persians were obliged to withdraw all armed forces and return Sassanid-ruled Egypt, the Levant and whatever imperial territories of Mesopotamia and Armenia were in Roman hands at the time of an earlier peace treaty in c. 595. The war had exhausted both the Byzantines and Sassanids, however, and left them extremely vulnerable to the Muslim forces that emerged in the following years.[74] The Byzantines suffered a crushing defeat by the Arabs at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636, while Ctesiphon fell in 637.[75]

The First Arab Siege of Constantinople (674–678) and the theme system

Greek fire was first used by the Byzantine Navy during the Byzantine–Arab Wars (from the Madrid Skylitzes, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid).

The Arabs, now firmly in control of Syria and the Levant, sent frequent raiding parties deep into Asia Minor, and in 674–678 laid siege to Constantinople itself. The Arab fleet was finally repulsed through the use of Greek fire, and a thirty-years' truce was signed between the Empire and the Umayyad Caliphate.[76] However, the Anatolian raids continued unabated, and accelerated the demise of classical urban culture, with the inhabitants of many cities either refortifying much smaller areas within the old city walls, or relocating entirely to nearby fortresses.[77] Constantinople itself dropped substantially in size, from 500,000 inhabitants to just 40,000–70,000, and, like other urban centres, it was partly ruralised. The city also lost the free grain shipments in 618, after Egypt fell first to the Persians and then to the Arabs, and public wheat distribution ceased.[78]

The void left by the disappearance of the old semi-autonomous civic institutions was filled by the system called theme, which entailed dividing Asia Minor into "provinces" occupied by distinct armies that assumed civil authority and answered directly to the imperial administration. This system may have had its roots in certain ad hoc measures taken by Heraclius, but over the course of the 7th century it developed into an entirely new system of imperial governance.[79] The massive cultural and institutional restructuring of the Empire consequent on the loss of territory in the 7th century has been said to have caused a decisive break in east Mediterranean Romanness and that the Byzantine state is subsequently best understood as another successor state rather than a real continuation of the Roman Empire.[80]

Late Heraclian dynasty

The withdrawal of large numbers of troops from the Balkans to combat the Persians and then the Arabs in the east opened the door for the gradual southward expansion of Slavic peoples into the peninsula, and, as in Asia Minor, many cities shrank to small fortified settlements.[81] In the 670s, the Bulgars were pushed south of the Danube by the arrival of the Khazars. In 680, Byzantine forces sent to disperse these new settlements were defeated.[82]

Constantine IV and his retinue, mosaic in Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe.

In 681, Constantine IV signed a treaty with the Bulgar khan Asparukh, and the new Bulgarian state assumed sovereignty over a number of Slavic tribes that had previously, at least in name, recognised Byzantine rule.[82] In 687–688, the final Heraclian emperor, Justinian II, led an expedition against the Slavs and Bulgarians, and made significant gains, although the fact that he had to fight his way from Thrace to Macedonia demonstrates the degree to which Byzantine power in the north Balkans had declined.[83]

Justinian II attempted to break the power of the urban aristocracy through severe taxation and the appointment of "outsiders" to administrative posts. He was driven from power in 695, and took shelter first with the Khazars and then with the Bulgarians. In 705, he returned to Constantinople with the armies of the Bulgarian khan Tervel, retook the throne, and instituted a reign of terror against his enemies. With his final overthrow in 711, supported once more by the urban aristocracy, the Heraclian dynasty came to an end.[84]

The Second Arab Siege of Constantinople (717–718) and the Isaurian dynasty

The Byzantine Empire at the accession of Leo III, c. 717. Striped area indicates land raided by the Arabs.

Gold solidus of Leo III (left), and his son and heir, Constantine V (right).

In 717 the Umayyad Caliphate launched the Siege of Constantinople (717–718) which lasted for one year. However, the combination of Leo III the Isaurian's military genius, the Byzantines' use of Greek Fire, a cold winter in 717–718, and Byzantine diplomacy with the Khan Tervel of Bulgaria resulted in a Byzantine victory. The Umayyads lost prestige and their best fighters as well which eventually resulted in unrest. After Leo III turned back the Muslim assault in 718, he addressed himself to the task of reorganising and consolidating the themes in Asia Minor. In 740 a major Byzantine victory took place at the Battle of Akroinon where the Byzantines destroyed the Umayyad army once again.

Leo III the Isaurian's son and successor, Constantine V, won noteworthy victories in northern Syria and also thoroughly undermined Bulgarian strength.[85] In 746, profiting by the unstable conditions in the Umayyad Caliphate, which was falling apart under Marwan II, Constantine V invaded Syria and captured Germanikeia. Coupled with military defeats on the other fronts of the overextended Caliphate and internal instability, the age of Arab expansion came to an end, and the Muslim world was divided, not to be united again.

Religious dispute over iconoclasm

The 8th and early 9th centuries were also dominated by controversy and religious division over Iconoclasm, which was the main political issue in the Empire for over a century. Icons (here meaning all forms of religious imagery) were banned by Leo and Constantine from around 730, leading to revolts by iconodules (supporters of icons) throughout the empire. After the efforts of empress Irene, the Second Council of Nicaea met in 787 and affirmed that icons could be venerated but not worshiped. Irene is said to have endeavoured to negotiate a marriage between herself and Charlemagne, but, according to Theophanes the Confessor, the scheme was frustrated by Aetios, one of her favourites.[86]

In the early 9th century, Leo V reintroduced the policy of iconoclasm, but in 843 empress Theodora restored the veneration of icons with the help of Patriarch Methodios.[87] Iconoclasm played a part in the further alienation of East from West, which worsened during the so-called Photian schism, when Pope Nicholas I challenged the elevation of Photios to the patriarchate.[88]

Macedonian dynasty and resurgence (867–1025)

The Byzantine Empire, c. 867

The accession of Basil I to the throne in 867 marks the beginning of the Macedonian dynasty, which would rule for the next two and a half centuries. This dynasty included some of the most able emperors in Byzantium's history, and the period is one of revival and resurgence. The Empire moved from defending against external enemies to reconquest of territories formerly lost.[89]

In addition to a reassertion of Byzantine military power and political authority, the period under the Macedonian dynasty is characterised by a cultural revival in spheres such as philosophy and the arts. There was a conscious effort to restore the brilliance of the period before the Slavic and subsequent Arab invasions, and the Macedonian era has been dubbed the "Golden Age" of Byzantium.[89] Although the Empire was significantly smaller than during the reign of Justinian, it had regained significant strength, as the remaining territories were less geographically dispersed and more politically, economically, and culturally integrated.

Wars against the Arabs

The general Leo Phokas defeats the Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo at Andrassos in 960, from the Madrid Skylitzes.

Taking advantage of the Empire's weakness after the Revolt of Thomas the Slav in the early 820s, the Arabs re-emerged and captured Crete. They also successfully attacked Sicily, but in 863 general Petronas gained a decisive victory against Umar al-Aqta, the emir of Melitene (Malatya). Under the leadership of emperor Krum, the Bulgarian threat also re-emerged, but in 815–816 Krum's son, Omurtag, signed a peace treaty with Leo V.[90]

During the reign of Theophilos, the empire created the Byzantine beacon system.

In the 830s Abbasid Caliphate started military excursions culminating with a victory in the Sack of Amorium. The Byzantines then attacked back and sacked Damietta in Egypt. Later the Abbasid Caliphate responded by sending their troops into Anatolia again, sacking and marauding until they were eventually annihilated by the Byzantines in 863.

In the early years of Basil I's reign, Arab raids on the coasts of Dalmatia were successfully repelled, and the region once again came under secure Byzantine control. This enabled Byzantine missionaries to penetrate to the interior and convert the Serbs and the principalities of modern-day Herzegovina and Montenegro to Orthodox Christianity.[91] An attempt to retake Malta ended disastrously, however, when the local population sided with the Arabs and massacred the Byzantine garrison.[92]

By contrast, the Byzantine position in Southern Italy was gradually consolidated so that by 873 Bari was once again under Byzantine rule,[91] and most of Southern Italy would remain in the Empire for the next 200 years.[92] On the more important eastern front, the Empire rebuilt its defences and went on the offensive. The Paulicians were defeated and their capital of Tephrike (Divrigi) taken, while the offensive against the Abbasid Caliphate began with the recapture of Samosata.[91]

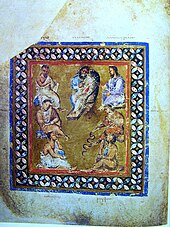

The military successes of the 10th century were coupled with a major cultural revival, the so-called Macedonian Renaissance. Miniature from the Paris Psalter, an example of Hellenistic-influenced art.

Under Basil's son and successor, Leo VI the Wise, the gains in the east against the now-weak Abbasid Caliphate continued. However, Sicily was lost to the Arabs in 902, and in 904 Thessaloniki, the Empire's second city, was sacked by an Arab fleet. The naval weakness of the Empire was rectified. Despite this revenge the Byzantines were still unable to strike a decisive blow against the Muslims, who inflicted a crushing defeat on the imperial forces when they attempted to regain Crete in 911.[93]

The death of the Bulgarian tsar Simeon I in 927 severely weakened the Bulgarians, allowing the Byzantines to concentrate on the eastern front.[94] Melitene was permanently recaptured in 934, and in 943 the famous general John Kourkouas continued the offensive in Mesopotamia with some noteworthy victories, culminating in the reconquest of Edessa. Kourkouas was especially celebrated for returning to Constantinople the venerated Mandylion, a relic purportedly imprinted with a portrait of Christ.[95]

The soldier-emperors Nikephoros II Phokas (reigned 963–969) and John I Tzimiskes (969–976) expanded the empire well into Syria, defeating the emirs of north-west Iraq. The great city of Aleppo was taken by Nikephoros in 962 and the Arabs were decisively expelled from Crete in 963. The recapture of Crete put an end to Arab raids in the Aegean allowing mainland Greece to flourish once again. Cyprus was permanently retaken in 965 and the successes of Nikephoros culminated in 969 with the recapture of Antioch, which he incorporated as a province of the Empire.[96] His successor John Tzimiskes recaptured Damascus, Beirut, Acre, Sidon, Caesarea, and Tiberias, putting Byzantine armies within striking distance of Jerusalem, although the Muslim power centres in Iraq and Egypt were left untouched.[97] After much campaigning in the north, the last Arab threat to Byzantium, the rich province of Sicily, was targeted in 1025 by Basil II, who died before the expedition could be completed. Nevertheless, by that time the Empire stretched from the straits of Messina to the Euphrates and from the Danube to Syria.[98]

Wars against the Bulgarian Empire

Emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025)

The traditional struggle with the See of Rome continued through the Macedonian period, spurred by the question of religious supremacy over the newly Christianised state of Bulgaria.[89] Ending eighty years of peace between the two states, the powerful Bulgarian tsar Simeon I invaded in 894 but was pushed back by the Byzantines, who used their fleet to sail up the Black Sea to attack the Bulgarian rear, enlisting the support of the Hungarians.[99] The Byzantines were defeated at the Battle of Boulgarophygon in 896, however, and agreed to pay annual subsidies to the Bulgarians.[93]

Leo the Wise died in 912, and hostilities soon resumed as Simeon marched to Constantinople at the head of a large army.[100] Although the walls of the city were impregnable, the Byzantine administration was in disarray and Simeon was invited into the city, where he was granted the crown of basileus (emperor) of Bulgaria and had the young emperor Constantine VII marry one of his daughters. When a revolt in Constantinople halted his dynastic project, he again invaded Thrace and conquered Adrianople.[101] The Empire now faced the problem of a powerful Christian state within a few days' marching distance from Constantinople,[89] as well as having to fight on two fronts.[93]

The extent of the Empire under Basil II

A great imperial expedition under Leo Phocas and Romanos I Lekapenos ended with another crushing Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Achelous in 917, and the following year the Bulgarians were free to ravage northern Greece. Adrianople was plundered again in 923, and a Bulgarian army laid siege to Constantinople in 924. Simeon died suddenly in 927, however, and Bulgarian power collapsed with him. Bulgaria and Byzantium entered a long period of peaceful relations, and the Empire was now free to concentrate on the eastern front against the Muslims.[102] In 968, Bulgaria was overrun by the Rus' under Sviatoslav I of Kiev, but three years later, John I Tzimiskes defeated the Rus' and re-incorporated Eastern Bulgaria into the Byzantine Empire.[103]

Bulgarian resistance revived under the rule of the Cometopuli dynasty, but the new Emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025) made the submission of the Bulgarians his primary goal.[104] Basil's first expedition against Bulgaria, however, resulted in a humiliating defeat at the Gates of Trajan. For the next few years, the emperor would be preoccupied with internal revolts in Anatolia, while the Bulgarians expanded their realm in the Balkans. The war dragged on for nearly twenty years. The Byzantine victories of Spercheios and Skopje decisively weakened the Bulgarian army, and in annual campaigns, Basil methodically reduced the Bulgarian strongholds.[104] At the Battle of Kleidion in 1014 the Bulgarians were annihilated: their army was captured, and it is said that 99 out of every 100 men were blinded, with the hundredth man left with one eye so he could lead his compatriots home. When Tsar Samuil saw the broken remains of his once formidable army, he died of shock. By 1018, the last Bulgarian strongholds had surrendered, and the country became part of the Empire.[104] This victory restored the Danube frontier, which had not been held since the days of the Emperor Heraclius.[98]

Relations with the Kievan Rus'

Rus' under the walls of Constantinople (860)

Between 850 and 1100, the Empire developed a mixed relationship with the new state of the Kievan Rus', which had emerged to the north across the Black Sea.[105] This relationship would have long-lasting repercussions in the history of the East Slavs, and the Empire quickly became the main trading and cultural partner for Kiev. The Rus' launched their first attack against Constantinople in 860, pillaging the suburbs of the city. In 941, they appeared on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus, but this time they were crushed, an indication of the improvements in the Byzantine military position after 907, when only diplomacy had been able to push back the invaders. Basil II could not ignore the emerging power of the Rus', and, following the example of his predecessors, he used religion as a means for the achievement of political purposes.[106] Rus'–Byzantine relations became closer following the marriage of Anna Porphyrogeneta to Vladimir the Great in 988, and the subsequent Christianisation of the Rus'.[105] Byzantine priests, architects, and artists were invited to work on numerous cathedrals and churches around Rus', expanding Byzantine cultural influence even further, while numerous Rus' served in the Byzantine army as mercenaries, most notably as the famous Varangian Guard.[105]

Even after the Christianisation of the Rus', however, relations were not always friendly. The most serious conflict between the two powers was the war of 968–971 in Bulgaria, but several Rus' raiding expeditions against the Byzantine cities of the Black Sea coast and Constantinople itself are also recorded. Although most were repulsed, they were often followed by treaties that were generally favourable to the Rus', such as the one concluded at the end of the war of 1043, during which the Rus' gave an indication of their ambitions to compete with the Byzantines as an independent power.[106]

Campaigns against Georgia

The integrity of the Byzantine empire itself was under serious threat after a full-scale rebellion, led by Bardas Skleros, broke out in 976. Following a series of successful battles the rebels swept across Asia Minor. In the urgency of the situation, Georgian prince David Kuropalate aided Basil II and after a decisive loyalist victory at the Battle of Pankaleia, he was rewarded by lifetime rule of key imperial territories in eastern Asia Minor. However, David's rebuff of Basil in Bardas Phocas’ revolt of 987 evoked Constantinople’s distrust of the Georgian rulers. After the failure of the revolt, David was forced to make Basil II the legatee of his extensive possessions. This agreement destroyed a previous arrangement by which David had made his adopted son, Bagrat III of Georgia, his heir. Basil gathered his inheritance upon David’s death in 1000 and reorganized provinces of Tao, Theodosiopolis, Phasiane and the Lake Van region (Apahunik) with the city of Manzikert – to the theme of Iberia.

The following year, the Georgian prince Gurgen, natural father of Bagrat III, marched to take David’s inheritance, but was thwarted by the Byzantine general Nikephoros Ouranos, dux of Antioch, forcing the successor Georgian Bagratids to recognize the new rearrangement. Bagrat’s son, George I, however, inherited a longstanding claim to David’s succession. Young and ambitious, George launched a campaign to restore the Kuropalates’ succession to Georgia and occupied Tao in 1015–1016. He also entered in an alliance with the Fatimid Caliph of Egypt, Al-Hakim (c.996–1021), that put Basil in a difficult situation, forcing him to refrain from an acute response to George's offensive.

A miniature depicting the defeat of the Georgian king George I ("Georgios of Abasgia") by the Byzantine emperor Basil. Skylitzes Matritensis, fol. 195v. George is shown as fleeing on horseback on the right and Basil holding a shield and lance on the left.

Beyond that, the Byzantines were at that time involved in a relentless war with the Bulgar Empire, limiting their actions to the west. But as soon as Bulgaria was conquered in 1018, and Al-Hakim was no longer alive, Basil led his army against Georgia. preparations for a larger-scale campaign against the Kingdom of Georgia were set in train, beginning with the re-fortification of Theodosiopolis. In the autumn of 1021, Basil, ahead of a large army, reinforced by the Varangian Guards, attacked the Georgians and their Armenian allies, recovering Phasiane and pushing on beyond the frontiers of Tao into inner Georgia. King George burned the city of Oltisi to keep it out of the enemy's hands and retreated to Kola. A bloody battle was fought near the village of Shirimni on Lake Palakazio (now Çildir, Turkey) on 11 September and the emperor won a costly victory, forcing George I to retreat northwards into his kingdom. Plundering the country on his way, Basil withdrew to winter at Trebizond.

Several attempts to negotiate the conflict went in vain and, in the meantime, George received reinforcements from the Kakhetians, and allied himself with the Byzantine commanders Nicephorus Phocas and Nicephorus Xiphias in their abortive insurrection in the emperor's rear. In December, George's ally, the Armenian King Senekerim of Vaspurakan, being harassed by the Seljuk Turks, surrendered his kingdom to the emperor. During the spring of 1022, Basil launched a final offensive, winning a crushing victory over the Georgians at Svindax. Menaced both by land and sea, King George handed over Tao, Phasiane, Kola, Artaan and Javakheti, and left his infant son Bagrat a hostage in Basil's hands.

Apex

Constantinople became the largest and wealthiest city in Europe between the 5th and 7th centuries, and between the 9th and the beginning of 13th centuries.

Basil II is considered among the most capable Byzantine emperors and his reign as the apex of the empire in the Middle Ages. By 1025, the date of Basil II's death, the Byzantine Empire stretched from Armenia in the east to Calabria in Southern Italy in the west.[98] Many successes had been achieved, ranging from the conquest of Bulgaria to the annexation of parts of Georgia and Armenia, and the reconquest of Crete, Cyprus, and the important city of Antioch. These were not temporary tactical gains but long-term reconquests.[91]

Leo VI achieved the complete codification of Byzantine law in Greek. This monumental work of 60 volumes became the foundation of all subsequent Byzantine law and is still studied today.[107] Leo also reformed the administration of the Empire, redrawing the borders of the administrative subdivisions (the Themata, or "Themes") and tidying up the system of ranks and privileges, as well as regulating the behaviour of the various trade guilds in Constantinople. Leo's reform did much to reduce the previous fragmentation of the Empire, which henceforth had one center of power, Constantinople.[108] However, the increasing military success of the Empire greatly enriched and empowered the provincial nobility with respect to the peasantry, who were essentially reduced to a state of serfdom.[109]

Under the Macedonian emperors, the city of Constantinople flourished, becoming the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, with a population of approximately 400,000 in the 9th and 10th centuries.[110] During this period, the Byzantine Empire employed a strong civil service staffed by competent aristocrats that oversaw the collection of taxes, domestic administration, and foreign policy. The Macedonian emperors also increased the Empire's wealth by fostering trade with Western Europe, particularly through the sale of silk and metalwork.[111]

Split between Orthodox Christianity and Catholicism (1054)

Mural of Saints Cyril and Methodius, 19th century, Troyan Monastery, Bulgaria

The Macedonian period also included events of momentous religious significance. The conversion of the Bulgarians, Serbs and Rus' to Orthodox Christianity permanently changed the religious map of Europe and still resonates today. Cyril and Methodius, two Byzantine Greek brothers from Thessaloniki, contributed significantly to the Christianization of the Slavs and in the process devised the Glagolitic alphabet, ancestor to the Cyrillic script.[112]

In 1054, relations between the Eastern and Western traditions within the Christian Church reached a terminal crisis, known as the East–West Schism. Although there was a formal declaration of institutional separation, on 16 July, when three papal legates entered the Hagia Sophia during Divine Liturgy on a Saturday afternoon and placed a bull of excommunication on the altar,[113] the so-called Great Schism was actually the culmination of centuries of gradual separation.[114] Unfortunately the legates did not know that the Pope had died, an event that made the excommunication void and the excommunication only applied to the Patriarch who responded by excommunicating the legates.

Crisis and fragmentation

The Empire soon fell into a period of difficulties, caused to a large extent by the undermining of the theme system and the neglect of the military. Nikephoros II, John Tzimiskes, and Basil II changed the military divisions (τάγματα, tagmata) from a rapid response, primarily defensive, citizen army into a professional, campaigning army, increasingly manned by mercenaries. Mercenaries were expensive, however, and as the threat of invasion receded in the 10th century, so did the need for maintaining large garrisons and expensive fortifications.[115] Basil II left a burgeoning treasury upon his death, but he neglected to plan for his succession. None of his immediate successors had any particular military or political talent and the administration of the Empire increasingly fell into the hands of the civil service. Efforts to revive the Byzantine economy only resulted in inflation and a debased gold coinage. The army was now seen as both an unnecessary expense and a political threat. Native troops were therefore cashiered and replaced by foreign mercenaries on specific contract.[116]

The seizure of Edessa (1031) by the Byzantines under George Maniakes and the counterattack by the Seljuk Turks

At the same time, the Empire was faced with new enemies. Provinces in southern Italy faced the Normans, who arrived in Italy at the beginning of the 11th century. During a period of strife between Constantinople and Rome culminating in the East-West Schism of 1054, the Normans began to advance, slowly but steadily, into Byzantine Italy.[117]Reggio, the capital of the tagma of Calabria, was captured in 1060 by Robert Guiscard, followed by Otranto in 1068. Bari, the main Byzantine stronghold in Apulia, was besieged in August 1068 and fell in April 1071.[118] The Byzantines also lost their influence over the Dalmatian coastal cities to Peter Krešimir IV of Croatia (r. 1058–1074/1075) in 1069.[119]

In 1048-9, the Seljuk Turks under Ibrahim Yinal made their first incursion into the Byzantine frontier region of Iberia and clashed with a combined Byzantine-Georgian army of 50,000 at the Battle of Kapetrou on 10 September 1048. The devastation left behind by the Seljuq raid was so fearful that the Byzantine magnate Eustathios Boilas described, in 1051/52, those lands as "foul and unmanageable... inhabited by snakes, scorpions, and wild beasts." The Arab chronicler Ibn al-Athir reports that Ibrahim brought back 100,000 captives and a vast booty loaded on the backs of ten thousand camels.[120]

About 1053 Constantine IX disbanded what the historian John Skylitzes calls the "Iberian Army", which consisted of 50,000 men and it was turned into a contemporary Drungary of the Watch. Two other knowledgeable contemporaries, the former officials Michael Attaleiates and Kekaumenos, agree with Skylitzes that by demobilizing these soldiers Constantine did catastrophic harm to the Empire's eastern defenses.

The emergency lent weight to the military aristocracy in Anatolia, who in 1068 secured the election of one of their own, Romanos Diogenes, as emperor. In the summer of 1071, Romanos undertook a massive eastern campaign to draw the Seljuks into a general engagement with the Byzantine army. At the Battle of Manzikert, Romanos suffered a surprise defeat by Sultan Alp Arslan, and he was captured. Alp Arslan treated him with respect and imposed no harsh terms on the Byzantines.[116] In Constantinople, however, a coup put in power Michael Doukas, who soon faced the opposition of Nikephoros Bryennios and Nikephoros Botaneiates. By 1081, the Seljuks had expanded their rule over virtually the entire Anatolian plateau from Armenia in the east to Bithynia in the west, and they had founded their capital at Nicaea, just 90 kilometres (56 miles) from Constantinople.[121]

Komnenian dynasty and the crusaders

Alexios I, founder of the Komnenos dynasty

During the Komnenian, or Comnenian, period from about 1081 to about 1185, the five emperors of the Komnenos dynasty (Alexios I, John II, Manuel I, Alexios II, and Andronikos I) presided over a sustained, though ultimately incomplete, restoration of the military, territorial, economic, and political position of the Byzantine Empire.[122] Although the Seljuk Turks occupied the heartland of the Empire in Anatolia, most Byzantine military efforts during this period were directed against Western powers, particularly the Normans.[122]

The Empire under the Komnenoi played a key role in the history of the Crusades in the Holy Land, which Alexios I had helped bring about, while also exerting enormous cultural and political influence in Europe, the Near East, and the lands around the Mediterranean Sea under John and Manuel. Contact between Byzantium and the "Latin" West, including the Crusader states, increased significantly during the Komnenian period. Venetian and other Italian traders became resident in large numbers in Constantinople and the empire (there were an estimated 60,000 Latins in Constantinople alone, out of a population of three to four hundred thousand), and their presence together with the numerous Latin mercenaries who were employed by Manuel helped to spread Byzantine technology, art, literature and culture throughout the Latin West, while also leading to a flow of Western ideas and customs into the Empire.[123]

In terms of prosperity and cultural life, the Komnenian period was one of the peaks in Byzantine history,[124] and Constantinople remained the leading city of the Christian world in size, wealth, and culture.[125] There was a renewed interest in classical Greek philosophy, as well as an increase in literary output in vernacular Greek.[126] Byzantine art and literature held a pre-eminent place in Europe, and the cultural impact of Byzantine art on the west during this period was enormous and of long lasting significance.[127]

Alexios I and the First Crusade

Province (theme) of the Byzantine Empire ca. 1045

After Manzikert, a partial recovery (referred to as the Komnenian restoration) was made possible by the Komnenian dynasty.[128] The first Komnenian emperor was Isaac I (1057–1059), after which the Doukas dynasty held power (1059–81). The Komnenoi attained power again under Alexios I in 1081. From the outset of his reign, Alexios faced a formidable attack by the Normans under Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund of Taranto, who captured Dyrrhachium and Corfu, and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly. Robert Guiscard's death in 1085 temporarily eased the Norman problem. The following year, the Seljuq sultan died, and the sultanate was split by internal rivalries. By his own efforts, Alexios defeated the Pechenegs; they were caught by surprise and annihilated at the Battle of Levounion on 28 April 1091.[129]

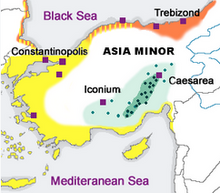

The Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm before the First Crusade (1095–1099)

Having achieved stability in the West, Alexios could turn his attention to the severe economic difficulties and the disintegration of the Empire's traditional defences.[130] However, he still did not have enough manpower to recover the lost territories in Asia Minor and to advance against the Seljuks. At the Council of Piacenza in 1095, envoys from Alexios spoke to Pope Urban II about the suffering of the Christians of the East, and underscored that without help from the West they would continue to suffer under Muslim rule.[131]

Urban saw Alexios's request as a dual opportunity to cement Western Europe and reunite the Eastern Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church under his rule.[131] On 27 November 1095, Pope Urban II called together the Council of Clermont, and urged all those present to take up arms under the sign of the Cross and launch an armed pilgrimage to recover Jerusalem and the East from the Muslims. The response in Western Europe was overwhelming.[129]

The brief first coinage of the Thessaloniki mint, opened by Alexios in September 1081, on his way to confront the invading Normans under Robert Guiscard

Alexios had anticipated help in the form of mercenary forces from the West, but he was totally unprepared for the immense and undisciplined force that soon arrived in Byzantine territory. It was no comfort to Alexios to learn that four of the eight leaders of the main body of the Crusade were Normans, among them Bohemund. Since the crusade had to pass through Constantinople, however, the Emperor had some control over it. He required its leaders to swear to restore to the empire any towns or territories they might reconquer from the Turks on their way to the Holy Land. In return, he gave them guides and a military escort.[132]

Alexios was able to recover a number of important cities and islands, and in fact much of western Asia Minor. Nevertheless, the Catholic/Latin crusaders believed their oaths were invalidated when Alexios did not help them during the siege of Antioch (he had in fact set out on the road to Antioch but had been persuaded to turn back by Stephen of Blois, who assured him that all was lost and that the expedition had already failed).[133] Bohemund, who had set himself up as Prince of Antioch, briefly went to war with the Byzantines, but he agreed to become Alexios' vassal under the Treaty of Devol in 1108, which marked the end of the Norman threat during Alexios' reign.[134]

John II, Manuel I and the Second Crusade

Medieval manuscript depicting the Capture of Jerusalem during the First Crusade

Alexios's son John II Komnenos succeeded him in 1118 and ruled until 1143. John was a pious and dedicated Emperor who was determined to undo the damage to the empire suffered at the Battle of Manzikert, half a century earlier.[135] Famed for his piety and his remarkably mild and just reign, John was an exceptional example of a moral ruler at a time when cruelty was the norm.[136] For this reason, he has been called the Byzantine Marcus Aurelius.

During his twenty-five year reign, John made alliances with the Holy Roman Empire in the West and decisively defeated the Pechenegs at the Battle of Beroia.[137] He thwarted Hungarian and Serbian threats during the 1120s, and in 1130 he allied himself with the German emperor Lothair III against the Norman king Roger II of Sicily.[138]

In the later part of his reign, John focused his activities on the East, personally leading numerous campaigns against the Turks in Asia Minor. His campaigns fundamentally altered the balance of power in the East, forcing the Turks onto the defensive, while restoring many towns, fortresses, and cities across the peninsula to the Byzantines. He defeated the Danishmend Emirate of Melitene and reconquered all of Cilicia, while forcing Raymond of Poitiers, Prince of Antioch, to recognise Byzantine suzerainty. In an effort to demonstrate the Emperor's role as the leader of the Christian world, John marched into the Holy Land at the head of the combined forces of the Empire and the Crusader states; yet despite his great vigour pressing the campaign, his hopes were disappointed by the treachery of his Crusader allies.[139] In 1142, John returned to press his claims to Antioch, but he died in the spring of 1143 following a hunting accident. Raymond was emboldened to invade Cilicia, but he was defeated and forced to go to Constantinople to beg mercy from the new Emperor.[140]

Byzantine Empire in orange, c. 1180, at the end of the Komnenian period

John's chosen heir was his fourth son, Manuel I Komnenos, who campaigned aggressively against his neighbours both in the west and in the east. In Palestine, Manuel allied with the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem and sent a large fleet to participate in a combined invasion of Fatimid Egypt. Manuel reinforced his position as overlord of the Crusader states, with his hegemony over Antioch and Jerusalem secured by agreement with Raynald, Prince of Antioch, and Amalric, King of Jerusalem.[141] In an effort to restore Byzantine control over the ports of southern Italy, he sent an expedition to Italy in 1155, but disputes within the coalition led to the eventual failure of the campaign. Despite this military setback, Manuel's armies successfully invaded the Southern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1167, defeating the Hungarians at the Battle of Sirmium. By 1168, nearly the whole of the eastern Adriatic coast lay in Manuel's hands.[142] Manuel made several alliances with the Pope and Western Christian kingdoms, and he successfully handled the passage of the Second Crusade through his empire.[143]

In the east, however, Manuel suffered a major defeat in 1176 at the Battle of Myriokephalon, against the Turks. Yet the losses were quickly recovered, and in the following year Manuel's forces inflicted a defeat upon a force of "picked Turks".[144] The Byzantine commander John Vatatzes, who destroyed the Turkish invaders at the Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir, not only brought troops from the capital but also was able to gather an army along the way, a sign that the Byzantine army remained strong and that the defensive program of western Asia Minor was still successful.[145]

12th-century Renaissance

'The Lamentation of Christ' (1164), a fresco from the church of Saint Panteleimon in Nerezi near Skopje; it is considered a superb example of 12th-century Komnenian art

John and Manuel pursued active military policies, and both deployed considerable resources on sieges and on city defences; aggressive fortification policies were at the heart of their imperial military policies.[146] Despite the defeat at Myriokephalon, the policies of Alexios, John and Manuel resulted in vast territorial gains, increased frontier stability in Asia Minor, and secured the stabilisation of the Empire's European frontiers. From c. 1081 to c. 1180, the Komnenian army assured the Empire's security, enabling Byzantine civilisation to flourish.[147]

This allowed the Western provinces to achieve an economic revival that continued until the close of the century. It has been argued that Byzantium under the Komnenian rule was more prosperous than at any time since the Persian invasions of the 7th century. During the 12th century, population levels rose and extensive tracts of new agricultural land were brought into production. Archaeological evidence from both Europe and Asia Minor shows a considerable increase in the size of urban settlements, together with a notable upsurge in new towns. Trade was also flourishing; the Venetians, the Genoese and others opened up the ports of the Aegean to commerce, shipping goods from the Crusader kingdoms of Outremer and Fatimid Egypt to the west and trading with the Empire via Constantinople.[148]

In artistic terms, there was a revival in mosaic, and regional schools of architecture began producing many distinctive styles that drew on a range of cultural influences.[149] During the 12th century, the Byzantines provided their model of early humanism as a renaissance of interest in classical authors. In Eustathius of Thessalonica, Byzantine humanism found its most characteristic expression.[150] In philosophy, there was resurgence of classical learning not seen since the 7th century, characterised by a significant increase in the publication of commentaries on classical works.[126] In addition, the first transmission of classical Greek knowledge to the West occurred during the Komnenian period.[127]

Decline and disintegration

Angelid dynasty

Byzantium in the late Angeloi period

Manuel's death on 24 September 1180 left his 11-year-old son Alexios II Komnenos on the throne. Alexios was highly incompetent at the office, but it was his mother, Maria of Antioch, and her Frankish background that made his regency unpopular.[151] Eventually, Andronikos I Komnenos, a grandson of Alexios I, launched a revolt against his younger relative and managed to overthrow him in a violent coup d'état.[152] Utilizing his good looks and his immense popularity with the army, he marched on to Constantinople in August 1182 and incited a massacre of the Latins.[152] After eliminating his potential rivals, he had himself crowned as co-emperor in September 1183. He eliminated Alexios II, and took his 12-year-old wife Agnes of France for himself.[152]

Andronikos began his reign well; in particular, the measures he took to reform the government of the Empire have been praised by historians. According to George Ostrogorsky, Andronikos was determined to root out corruption: Under his rule, the sale of offices ceased; selection was based on merit, rather than favouritism; officials were paid an adequate salary so as to reduce the temptation of bribery. In the provinces, Andronikos's reforms produced a speedy and marked improvement.[153] The aristocrats were infuriated against him, and to make matters worse, Andronikos seems to have become increasingly unbalanced; executions and violence became increasingly common, and his reign turned into a reign of terror.[154] Andronikos seemed almost to seek the extermination of the aristocracy as a whole. The struggle against the aristocracy turned into wholesale slaughter, while the Emperor resorted to ever more ruthless measures to shore up his regime.[153]

Despite his military background, Andronikos failed to deal with Isaac Komnenos, Béla III of Hungary (r. 1172–1196) who reincorporated Croatian territories into Hungary, and Stephen Nemanja of Serbia (r. 1166–1196) who declared his independence from the Byzantine Empire. Yet, none of these troubles would compare to William II of Sicily's (r. 1166–1189) invasion force of 300 ships and 80,000 men, arriving in 1185.[155] Andronikos mobilised a small fleet of 100 ships to defend the capital, but other than that he was indifferent to the populace. He was finally overthrown when Isaac Angelos, surviving an imperial assassination attempt, seized power with the aid of the people and had Andronikos killed.[156]

The reign of Isaac II, and more so that of his brother Alexios III, saw the collapse of what remained of the centralised machinery of Byzantine government and defence. Although the Normans were driven out of Greece, in 1186 the Vlachs and Bulgars began a rebellion that led to the formation of the Second Bulgarian Empire. The internal policy of the Angeloi was characterised by the squandering of the public treasure and fiscal maladministration. Imperial authority was severely weakened, and the growing power vacuum at the center of the Empire encouraged fragmentation. There is evidence that some Komnenian heirs had set up a semi-independent state in Trebizond before 1204.[157] According to Alexander Vasiliev, "the dynasty of the Angeloi, Greek in its origin, ... accelerated the ruin of the Empire, already weakened without and disunited within."[158]

Fourth Crusade

The Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople, by Eugène Delacroix (1840)

In 1198, Pope Innocent III broached the subject of a new crusade through legates and encyclical letters.[159] The stated intent of the crusade was to conquer Egypt, now the centre of Muslim power in the Levant. The crusader army that arrived at Venice in the summer of 1202 was somewhat smaller than had been anticipated, and there were not sufficient funds to pay the Venetians, whose fleet was hired by the crusaders to take them to Egypt. Venetian policy under the ageing and blind but still ambitious Doge Enrico Dandolo was potentially at variance with that of the Pope and the crusaders, because Venice was closely related commercially with Egypt.[160] The crusaders accepted the suggestion that in lieu of payment they assist the Venetians in the capture of the (Christian) port of Zara in Dalmatia (vassal city of Venice, which had rebelled and placed itself under Hungary's protection in 1186).[161] The city fell in November 1202 after a brief siege.[162] Innocent tried to forbid this political attack on a Christian city, but was ignored. Reluctant to jeopardise his own agenda for the Crusade, he gave conditional absolution to the crusaders—not, however, to the Venetians.[160]

After the death of Theobald III, Count of Champagne, the leadership of the Crusade passed to Boniface of Montferrat, a friend of the Hohenstaufen Philip of Swabia. Both Boniface and Philip had married into the Byzantine Imperial family. In fact, Philip's brother-in-law, Alexios Angelos, son of the deposed and blinded Emperor Isaac II Angelos, had appeared in Europe seeking aid and had made contacts with the crusaders. Alexios offered to reunite the Byzantine church with Rome, pay the crusaders 200,000 silver marks, join the crusade and provide all the supplies they needed to get to Egypt.[163] Innocent was aware of a plan to divert the Crusade to Constantinople and forbade any attack on the city, but the papal letter arrived after the fleets had left Zara.

Crusader sack of Constantinople (1204)

The partition of the empire following the Fourth Crusade, c. 1204

The crusaders arrived at Constantinople in the summer of 1203 and quickly attacked, starting a major fire that damaged large parts of the city, and briefly seized control. Alexios III fled from the capital and Alexios Angelos was elevated to the throne as Alexios IV along with his blind father Isaac. Alexios IV and Isaac II were unable to keep their promises and were deposed by Alexios V. The crusaders again took the city on 13 April 1204 and Constantinople was subjected to pillage and massacre by the rank and file for three days. Many priceless icons, relics and other objects later turned up in Western Europe, a large number in Venice. According to Choniates, a prostitute was even set up on the Patriarchal throne.[164] When Innocent III heard of the conduct of his crusaders, he castigated them in no uncertain terms but the situation was beyond his control, especially after his legate, on his own initiative, had absolved the crusaders from their vow to proceed to the Holy Land.[160] When order had been restored, the crusaders and the Venetians proceeded to implement their agreement; Baldwin of Flanders was elected Emperor of a new Latin Empire and the Venetian Thomas Morosini was chosen as Patriarch. The lands divided up among the leaders included most of the former Byzantine possessions, though resistance would continue through the Byzantine remnants of Nicaea, Trebizond, and Epirus.[160] Although Venice was more interested in commerce than conquering territory, it took key areas of Constantinople and the Doge took the title of "Lord of a Quarter and Half a Quarter of the Roman Empire".[165]

Fall

Empire in exile

After the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Latin crusaders, two Byzantine successor states were established: the Empire of Nicaea, and the Despotate of Epirus. A third, the Empire of Trebizond, was created after Alexios Komnenos, commanding the Georgian expedition in Chaldia[166] a few weeks before the sack of Constantinople, found himself de facto emperor, and established himself in Trebizond. Of the three successor states, Epirus and Nicaea stood the best chance of reclaiming Constantinople. The Nicaean Empire struggled to survive the next few decades, however, and by the mid-13th century it had lost much of southern Anatolia.[167] The weakening of the Sultanate of Rûm following the Mongol invasion in 1242–43 allowed many beyliks and ghazis to set up their own principalities in Anatolia, weakening the Byzantine hold on Asia Minor.[168] In time, one of the Beys, Osman I, created an empire that would eventually conquer Constantinople. However, the Mongol invasion also gave Nicaea a temporary respite from Seljuk attacks, allowing it to concentrate on the Latin Empire to its north.

Reconquest of Constantinople

The Byzantine Empire, c. 1263

The Empire of Nicaea, founded by the Laskarid dynasty, managed to effect the Recapture of Constantinople from the Latins in 1261 and defeat Epirus. This led to a short-lived revival of Byzantine fortunes under Michael VIII Palaiologos but the war-ravaged Empire was ill-equipped to deal with the enemies that surrounded it. To maintain his campaigns against the Latins, Michael pulled troops from Asia Minor and levied crippling taxes on the peasantry, causing much resentment.[169] Massive construction projects were completed in Constantinople to repair the damage of the Fourth Crusade but none of these initiatives was of any comfort to the farmers in Asia Minor suffering raids from Muslim ghazis.[170]

Rather than holding on to his possessions in Asia Minor, Michael chose to expand the Empire, gaining only short-term success. To avoid another sacking of the capital by the Latins, he forced the Church to submit to Rome, again a temporary solution for which the peasantry hated Michael and Constantinople.[170] The efforts of Andronikos II and later his grandson Andronikos III marked Byzantium's last genuine attempts in restoring the glory of the Empire. However, the use of mercenaries by Andronikos II would often backfire, with the Catalan Company ravaging the countryside and increasing resentment towards Constantinople.[171]

Rise of the Ottomans and fall of Constantinople

The siege of Constantinople in 1453, depicted in a 15th-century French miniature

The situation became worse for Byzantium during the civil wars after Andronikos III died. A six-year-long civil war devastated the empire, allowing the Serbian ruler Stefan Dušan (r. 1331–1346) to overrun most of the Empire's remaining territory and establish a Serbian Empire. In 1354, an earthquake at Gallipoli devastated the fort, allowing the Ottomans (who were hired as mercenaries during the civil war by John VI Kantakouzenos) to establish themselves in Europe.[172] By the time the Byzantine civil wars had ended, the Ottomans had defeated the Serbians and subjugated them as vassals. Following the Battle of Kosovo, much of the Balkans became dominated by the Ottomans.[173]

The Byzantine emperors appealed to the West for help, but the Pope would only consider sending aid in return for a reunion of the Eastern Orthodox Church with the See of Rome. Church unity was considered, and occasionally accomplished by imperial decree, but the Orthodox citizenry and clergy intensely resented the authority of Rome and the Latin Rite.[174] Some Western troops arrived to bolster the Christian defence of Constantinople, but most Western rulers, distracted by their own affairs, did nothing as the Ottomans picked apart the remaining Byzantine territories.[175]