Gupta Empire

Gupta Empire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd century CE–590 CE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

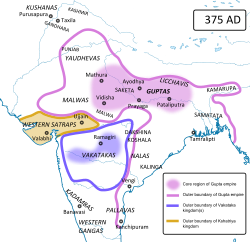

Approximate extent of the Gupta territories (purple) in 375 CE. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

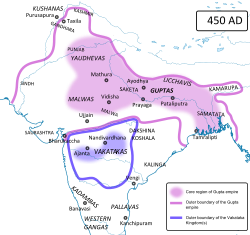

Approximate extent of the Gupta territories (purple) in 450 CE. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Pataliputra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit (literary and academic); Prakrit (vernacular) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient India | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 3rd century CE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 590 CE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 400 | 3,500,000[1] km2 (1,400,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire existing from the mid-to-late 3rd century CE to 590 CE. At its zenith, from approximately 319 to 550 CE, it covered much of the Indian subcontinent.[2] This period is called the Golden Age of India by some historians,[3] although this characterization has been disputed by others.[4] The ruling dynasty of the empire was founded by the king Sri Gupta; the most notable rulers of the dynasty were Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, and Chandragupta II. The 5th-century CE Sanskrit poet Kalidasa credits the Guptas with having conquered about twenty-one kingdoms, both in and outside India, including the kingdoms of Parasikas, the Hunas, the Kambojas, tribes located in the west and east Oxus valleys, the Kinnaras, Kiratas, and others.[5][non-primary source needed]

The high points of this period are the great cultural developments which took place during the reign of Chandragupta II. All literary sources, such as Mahabharata and Ramayana, were canonised during this period.[6] The Gupta period produced scholars such as Kalidasa,[7]Aryabhata, Varahamihira, and Vatsyayana who made great advancements in many academic fields.[8][9][10] Science and political administration reached new heights during the Gupta era. The period gave rise to achievements in architecture, sculpture, and painting that "set standards of form and taste [that] determined the whole subsequent course of art, not only in India but far beyond her borders".[11] Strong trade ties also made the region an important cultural centre and established the region as a base that would influence nearby kingdoms and regions in Burma, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia.[12][unreliable source?] The Puranas, earlier long poems on a variety of subjects, are also thought to have been committed to written texts around this period.[11]

The empire eventually died out because of many factors such as substantial loss of territory and imperial authority caused by their own erstwhile feudatories, as well as the invasion by the Huna peoples (Kidarites and Alchon Huns) from Central Asia.[13][14] After the collapse of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century, India was again ruled by numerous regional kingdoms. A minor line of the Gupta clan continued to rule Magadha after the disintegration of the empire. These Guptas were ultimately ousted by the Vardhana ruler Harsha, who established his empire in the first half of the 7th century.[citation needed]

Contents

1 Origin

2 History

2.1 Early rulers

2.2 Samudragupta

2.3 Ramagupta

2.4 Chandragupta II "Vikramaditya"

2.4.1 Chandragupta II's Campaigns against Foreign Tribes

2.4.2 Faxian

2.5 Kumaragupta I

2.6 Skandagupta

2.7 Decline of the empire

3 Military organization

4 Religion

5 Gupta administration

6 Legacy of the Gupta Empire

7 Art and architecture

8 References

8.1 Bibliography

9 External links

Origin

Gupta Empire 320 CE–550 CE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The homeland of the Guptas is uncertain.[15] According to one theory, they originated in the present-day eastern Uttar Pradesh, where most of the inscriptions and coins of the early Gupta kings have been discovered.[16][17] The proponents of this theory argue that according to the Puranas, the territory of the early Gupta kings included Prayaga, Saketa, and other areas in the Ganges basin.[18][19] Another prominent theory locates the Gupta homeland in the present-day Bengal region, based on the account of the 7th century Chinese Buddhist monk Yijing. According to Yijing, king Che-li-ki-to (identified with the dynasty's founder Shri Gupta) built a temple for Chinese pilgrims near Mi-li-kia-si-kia-po-no (apparently a transcription of Mriga-shikha-vana). Yijing states that this temple was located more than 40 yojanas east of Nalanda, which would mean it was situated somewhere in the modern Bengal region.[20] Another proposal is that the early Gupta kingdom extended from Prayaga in the west to northern Bengal in the east.[21]

The Gupta records do not mention the dynasty's varna (social class).[22] Some historians, such as A. S. Altekar, have theorized that they were of Vaishya origin, as some ancient Indian texts prescribe the name "Gupta" for the members of the Vaishya varna.[23][24] Critics of this theory point out that the suffix Gupta features in the names of several non-Vaishyas before as well as during the Gupta period,[25] and the dynastic name "Gupta" may have simply derived from the name of the family's first king Gupta.[26] Some scholars, such as S. R. Goyal, theorize that the Guptas were Brahmanas, because they had matrimonial relations with Brahmanas, but others reject this evidence as inconclusive.[27] Based on the Pune and Riddhapur inscriptions of the Gupta princess Prabhavati-gupta, some scholars believe that the name of her paternal gotra (clan) was "Dharana", but an alternative reading of these inscriptions suggests that Dharana was the gotra of her mother Kuberanaga.[28]

History

Early rulers

Queen Kumaradevi and King Chandragupta I, depicted on a gold coin

Gupta (fl. late 3rd century CE) is the earliest known king of the dynasty: different historians variously date the beginning of his reign from mid-to-late 3rd century CE.[29][30] "Che-li-ki-to", the name of a king mentioned by the 7th century Chinese Buddhist monk Yijing, is believed to be a transcription of "Shri-Gupta" (IAST: Śrigupta), "Shri" being an honorific prefix.[31] According to Yijing, this king built a temple for Chinese Buddhist pilgrims near "Mi-li-kia-si-kia-po-no" (believed to be a transcription of Mṛgaśikhāvana).[32]

In the Allahabad Pillar inscription, Gupta and his successor Ghatotkacha are described as Maharaja ("great king"), while the next king Chandragupta I is called a Maharajadhiraja ("king of great kings"). In the later period, the title Maharaja was used by feudatory rulers, which has led to suggestions that Gupta and Ghatotkacha were vassals (possibly of Kushan Empire).[33] However, there are several instances of paramount sovereigns using the title Maharaja, in both pre-Gupta and post-Gupta periods, so this cannot be said with certainty. That said, there is no doubt that Gupta and Ghatotkacha held a lower status and were less powerful than Chandragupta I.[34]

Chandragupta I married the Lichchhavi princess Kumaradevi, which may have helped him extend his political power and dominions, enabling him to adopt the imperial title Maharajadhiraja.[35] According to the dynasty's official records, he was succeeded by his son Samudragupta. However, the discovery of the coins issued by a Gupta ruler named Kacha have led to some debate on this topic: according to one theory, Kacha was another name for Samudragupta; another possibility is that Kacha was a rival claimant to the throne.[36]

Samudragupta

Coin of Samudragupta, with Garuda pillar. British Museum.

Samudragupta, Parakramanka succeeded his father in 335, and ruled for about 45 years, until his death in 380. He took the kingdoms of Ahichchhatra and Padmavati early in his reign. He then attacked the Malwas, the Yaudheyas, the Arjunayanas, the Maduras and the Abhiras, all of which were tribes in the area. By his death in 380, he had incorporated over twenty kingdoms into his realm and his rule extended from the Himalayas to the river Narmada and from the Brahmaputra to the Yamuna. He gave himself the titles King of Kings and World Monarch. Historian Vincent Smith described him as the "Indian Napoleon".[37] He performed Ashwamedha Yajna in which a horse with an army is sent to all the nearby territories of friends and foes. These territorial kings on arrival either accept the king's alliance, who is performing this Yajna, or fight if they do not. The stone replica of the horse, then prepared, is in the Lucknow Museum. The Samudragupta Prashasti inscribed on the Ashokan Pillar, now in Akbar’s Fort at Allahabad, is an authentic record of his exploits and his sway over most of the continent.

Samudragupta was not only a talented military leader but also a great patron of art and literature. He conquered what is now Kashmir and Afghanistan, enlarging the empire.[38] The critical scholars present in his court were Harishena, Vasubandhu, and Asanga. He was a poet and musician himself. He was a firm believer in Hinduism and is known to have worshipped Lord Vishnu. He was considerate of other religions and allowed Sri Lanka's Buddhist king Sirimeghvanna to build a monastery at Bodh Gaya. That monastery was called by Xuanzang as the Mahabodhi Sangharama.[39][unreliable source?] He provided a gold railing around the Bodhi Tree.

Ramagupta

Head of Tirthankara, Mathura Museum

Although, the narrative of the Devichandragupta is not supported by any contemporary epigraphical evidence, the historicity of Rama Gupta is proved by his Durjanpur inscriptions on three Jaina images, where he is mentioned as the Maharajadhiraja. A large number of his copper coins also have been found from the Eran-Vidisha region and classified in five distinct types, which include the Garuda,[40]Garudadhvaja, lion and border legend types. The Brahmi legends on these coins are written in the early Gupta style.[41] In the opinion of art historian Dr. R. A. Agarawala, D. Litt., Rama Gupta may be the eldest son of Samudragupta. He became king because of being the eldest. It is possible that he was dethroned because of being considered unfit to rule, and his younger brother Chandragupta II took over.

Chandragupta II "Vikramaditya"

Krishna fighting the horse demon Keshi, 5th century

According to the Gupta records, amongst his sons, Samudragupta nominated prince Chandragupta II, born of queen Dattadevi, as his successor. Chandragupta II, Vikramaditya (the Sun of Power), ruled from 375 until 415. He married a Kadamba princess of Kuntala and of Naga lineage (Nāgakulotpannnā), Kuberanaga. His daughter Prabhavatigupta from this Naga queen was married to Rudrasena II, the Vakataka ruler of Deccan.[42] His son Kumaragupta I was married to a Kadamba princess of the Karnataka region. Chandragupta II expanded his realm westwards, defeating the Saka Western Kshatrapas of Malwa, Gujarat and Saurashtra in a campaign lasting until 409. His main opponent Rudrasimha III was defeated by 395, and he crushed the Bengal chiefdoms. This extended his control from coast to coast, established a second capital at Ujjain and was the high point of the empire.

Gold coins of Chandragupta II.

Despite the creation of the empire through war, the reign is remembered for its very influential style of Hindu art, literature, culture and science, especially during the reign of Chandragupta II. Some excellent works of Hindu art such as the panels at the Dashavatara Temple in Deogarh serve to illustrate the magnificence of Gupta art. Above all it was the synthesis of elements that gave Gupta art its distinctive flavour. During this period, the Guptas were supportive of thriving Buddhist and Jain cultures as well, and for this reason there is also a long history of non-Hindu Gupta period art. In particular, Gupta period Buddhist art was to be influential in most of East and Southeast Asia. Many advances were recorded by the Chinese scholar and traveller Faxian (Fa-hien) in his diary and published afterwards.

The court of Chandragupta was made even more illustrious by the fact that it was graced by the Navaratna (Nine Jewels), a group of nine who excelled in the literary arts. Amongst these men was the immortal Kālidāsa whose works dwarfed the works of many other literary geniuses, not only in his own age but in the years to come. Kalidasa was mainly known for his subtle exploitation of the shringara (romantic) element in his verse.

Chandragupta II's Campaigns against Foreign Tribes

The 4th century Sanskrit poet Kalidasa credits Chandragupta Vikramaditya with conquering about twenty one kingdoms, both in and outside India. After finishing his campaign in East and West India, Vikramaditya (Chandragupta II) proceeded northwards, subjugated the Parasikas, then the Hunas and the Kambojas tribes located in the west and east Oxus valleys respectively. Thereafter, the king proceeded into the Himalaya mountains to reduce the mountain tribes of the Kinnaras, Kiratas, as well as India proper.[5][non-primary source needed]

The Brihatkathamanjari of the Kashmiri writer Kshemendra states, King Vikramaditya (Chandragupta II) had "unburdened the sacred earth of the Barbarians like the Sakas, Mlecchas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Tusharas, Parasikas, Hunas, and others, by annihilating these sinful Mlecchas completely".[43][non-primary source needed][44][45][unreliable source?]

Faxian

Faxian (or Fa Hsien etc.), a Chinese Buddhist, was one of the pilgrims who visited India during the reign of the Gupta emperor Chandragupta II. He started his journey from China in 399 and reached India in 405. During his stay in India up to 411, he went on a pilgrimage to Mathura, Kannauj, Kapilavastu, Kushinagar, Vaishali, Pataliputra, Kashi, and Rajagriha, and made careful observations about the empire's conditions. Faxian was pleased with the mildness of administration. The Penal Code was mild and offenses were punished by fines only. From his accounts, the Gupta Empire was a prosperous period. And until the Rome-China trade axis was broken with the fall of the Han dynasty, the Guptas did indeed prosper. His writings form one of the most important sources for the history of this period.

Kumaragupta I

Silver coin of the Gupta King Kumaragupta I (Coin of his Western territories, design derived from the Western Satraps).

Obv: Bust of king with crescents, with traces of corrupt Greek script.[46][47]

Rev: Garuda standing facing with spread wings. Brahmi legend: Parama-bhagavata rajadhiraja Sri Kumaragupta Mahendraditya.

Chandragupta II was succeeded by his second son Kumaragupta I, born of Mahadevi Dhruvasvamini. Kumaragupta I assumed the title, Mahendraditya.[48] He ruled until 455. Towards the end of his reign a tribe in the Narmada valley, the Pushyamitras, rose in power to threaten the empire. The Kidarites as well probably confronted the Gupta Empire towards the end of the rule of Kumaragupta I, as his son Skandagupta mentions in the Bhitari pillar inscription his efforts at reshaping a country in disarray, through reorganization and military victories over the Pushyamitras and the Hunas.[49]

He was the founder of Nalanda University which on July 15, 2016 was declared as a UNESCO world heritage site.[50]

Skandagupta

Skandagupta, son and successor of Kumaragupta I is generally considered to be the last of the great Gupta rulers. He assumed the titles of Vikramaditya and Kramaditya.[51] He defeated the Pushyamitra threat, but then was faced with invading Kidarites (sometimes described as the Hephthalites or "White Huns", known in India as the Sweta Huna), from the northwest.

He repelled a Huna attack around 455 CE, but the expense of the wars drained the empire's resources and contributed to its decline. The Bhitari Pillar inscription of Skandagupta, the successor of Chandragupta, recalls the near-annihilation of the Gupta Empire following the attacks of the Kidarites.[52] The Kidarites seem to have retained the western part of the Gupta Empire.[52]

Skandagupta died in 467 and was succeeded by his agnate brother Purugupta.[53]

Decline of the empire

The Alchon Huns under Toramana and his son Mihirakula (here depicted) gravely weakened the Gupta Empire.

Following Skandagupta's death, the empire was clearly in decline.[54] He was followed by Purugupta (467–473), Kumaragupta II (473–476), Budhagupta (476–495), Narasimhagupta (495—?), Kumaragupta III (530—540), Vishnugupta (540—550), two lesser known kings namely, Vainyagupta and Bhanugupta.

In the 480's the Alchon Huns under Toramana and Mihirakula broke through the Gupta defenses in the northwest, and much of the empire in the northwest was overrun by the Huns by 500. The empire disintegrated under the attacks of Toramana and his successor Mihirakula. It appears from inscriptions that the Guptas, although their power was much diminished, continued to resist the Huns. The Hun invader Toramana was defeated by Bhanugupta in 510.[55][56] The Huns were defeated and driven out of India in 528 by king Yashodharman from Malwa, and possibly Gupta emperor Narasimhagupta.[57]

The much-weakened Late Guptas, circa 550 CE.

These invasions, although only spanning a few decades, had long term effects on India, and in a sense brought an end to Classical Indian civilization.[58] Soon after the invasions, the Gupta Empire, already weakened by these invasions and the rise of local rulers such as Yashodharman, ended as well.[59] Following the invasions, northern India was left in disarray, with numerous smaller Indian powers emerging after the crumbling of the Guptas.[60] The Huna invasions are said to have seriously damaged India's trade with Europe and Central Asia.[58] In particular, Indo-Roman trade relations, which the Gupta Empire had greatly benefited from. The Guptas had been exporting numerous luxury products such as silk, leather goods, fur, iron products, ivory, pearl, and pepper from centres such as Nasik, Paithan, Pataliputra, and Benares. The Huna invasion probably disrupted these trade relations and the tax revenues that came with them.[61]

Furthermore, Indian urban culture was left in decline, and Buddhism, gravely weakened by the destruction of monasteries and the killing of monks by the hand of the vehemently anti-Buddhist Shaivist Mihirakula, started to collapse.[58] Great centres of learning were destroyed, such as the city of Taxila, bringing cultural regression.[58] During their rule of 60 years, the Alchons are said to have altered the hierarchy of ruling families and the Indian caste system. For example, the Hunas are often said to have become the precursors of the Rajputs.[58]

The succession of the 6th-century Guptas is not entirely clear, but the tail end recognized ruler of the dynasty's main line was king Vishnugupta, reigning from 540 to 550. In addition to the Hun invasion, the factors, which contribute to the decline of the empire include competition from the Vakatakas and the rise of Yashodharman in Malwa.[62]

The last known inscription by a Gupta emperor is from the reign of Vishnugupta (the Damodarpur copper-plate inscription),[63] in which he makes a land grant in the area of Kotivarsha (Bangarh in West Bengal) in 542/543 CE.[64] This follows the occupation of most of northern and central India by the Aulikara ruler Yashodharman circa 532 CE.[64]

Military organization

Gold coin of Gupta era, depicting Gupta king Kumaragupta holding a bow.

Sculpture of Vishnu (red sandstone), 5th century CE

The Imperial Guptas couldn't have achieved their successes through force of arms without an efficient martial system. Historically, the best accounts of this not only come from Indian sources themselves but from Chinese and Western observers. However, a contemporary Indian document, regarded as a military classic of the time, the Siva-Dhanur-veda, offers some insight into the military system of the Guptas.[citation needed]

The Guptas seem to have relied heavily on infantry archers, and the bow was one of the dominant weapons of their army. The Indian version of the longbow was composed of metal, or more typically bamboo, and fired a long bamboo cane arrow with a metal head.[citation needed] Unlike the composite bows of Western and Central Asian foes, bows of this design would be less prone to warping in the damp and moist conditions often prevalent to the region. The Indian longbow was reputedly a powerful weapon capable of great range and penetration and provided an effective counter to invading horse archers. Iron shafts were used against armored elephants and fire arrows were not part of the bowmen's arsenal, contrary to popular belief. India historically has had a prominent reputation for its steel weapons. One of these was the steel bow. Because of its high tensility, the steel bow was capable of long range and penetration of exceptionally thick armor. These were less common weapons than the bamboo design and found in the hands of noblemen rather than in the ranks. Archers were frequently protected by infantry equipped with shields, javelins, and longswords. The Guptas also had knowledge of siegecraft, catapults, and other sophisticated war machines.[citation needed]

The Guptas apparently showed little predilection for using horse archers, despite the fact these warriors were a primary component in the ranks of their Scythian, Parthian, and Hepthalite (Huna) enemies. However, the Gupta armies were probably better disciplined. Able commanders such as Samudragupta and Chandragupta II would have likely understood the need for combined armed tactics and proper logistical organization. Gupta military success likely stemmed from the concerted use of elephants, armored cavalry, steel bow and foot archers in tandem against both Hindu kingdoms and foreign armies invading from the Northwest. The Guptas also maintained a navy, allowing them to control regional waters.[citation needed]

The collapse of the Gupta Empire in the face of the Huna onslaught was due not directly to the inherent defects of the Gupta army, which after all had initially defeated these people under Skandagupta. More likely, internal dissolution sapped the ability of the Guptas to resist foreign invasion, as was simultaneously occurring in Western Europe and China.[citation needed]

During the reign of Chandragupta II, Gupta Empire maintained a large army consisting of 500,000 infantry, 50,000 cavalry, 20,000 charioteers and 10,000 elephants[citation needed] along with a powerful navy with more than 1200 ships[citation needed]. Chandragupta II controlled the whole of the Indian subcontinent;[2] the Gupta empire was the most powerful empire in the world during his reign, at a time when the Roman Empire in the West was in decline.[citation needed]

Religion

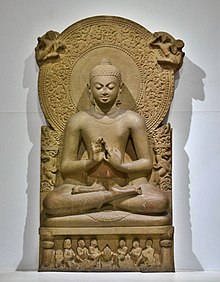

Meditating Buddha from the Gupta era, 5th century CE.

The Guptas were traditionally a Hindu dynasty.[65] They were orthodox Hindus, but did not force their beliefs on the rest of the population, as Buddhism and Jainism also were encouraged.[66]Sanchi remained an important centre of Buddhism.[66]Kumaragupta I (c. 414 – c. 455 CE) is said to have founded Nalanda.[66]

Some later rulers however seem to have especially favoured Buddhism. Narasimhagupta Baladitya (c. 495-?), according to contemporary writer Paramartha, was brought up under the influence of the Mahayanist philosopher, Vasubandhu.[65] He built a sangharama at Nalanda and also a 300 ft (91 m) high vihara with a Buddha statue within which, according to Xuanzang, resembled the "great Vihara built under the Bodhi tree". According to the Manjushrimulakalpa (c. 800 CE), king Narasimhsagupta became a Buddhist monk, and left the world through meditation (Dhyana).[65] The Chinese monk Xuanzang also noted that Narasimhagupta Baladitya's son, Vajra, who commissioned a sangharama as well, "possessed a heart firm in faith".[67]:45[68]:330

Gupta administration

A study of the epigraphical records of the Gupta empire shows that there was a hierarchy of administrative divisions from top to bottom. The empire was called by various names such as Rajya, Rashtra, Desha, Mandala, Prithvi and Avani. It was divided into 26 provinces, which were styled as Bhukti, Pradesha and Bhoga. Provinces were also divided into Vishayas and put under the control of the Vishayapatis. A Vishayapati administered the Vishaya with the help of the Adhikarana (council of representatives), which comprised four representatives: Nagarasreshesthi, Sarthavaha, Prathamakulike and Prathama Kayastha. A part of the Vishaya was called Vithi.[69] There were also trade links of Gupta business with the Roman empire.

Legacy of the Gupta Empire

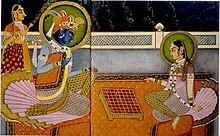

Later image of Krishna and Radha playing chaturanga on an 8 × 8 Ashtāpada

Scholars of this period include Varahamihira and Aryabhata, who is believed to be the first to come up with the concept of zero, postulated the theory that the Earth moves round the Sun, and studied solar and lunar eclipses. Kalidasa, who was a great playwright, who wrote plays such as Shakuntala, and marked the highest point of Sanskrit literature is also said to have belonged to this period. The Sushruta Samhita, which is a Sanskrit redaction text on all of the major concepts of ayurvedic medicine with innovative chapters on surgery, dates to the Gupta period.

Chess is said to have originated in this period,[70] where its early form in the 6th century was known as caturaṅga, which translates as "four divisions [of the military]" – infantry, cavalry, elephantry, and chariotry – represented by the pieces that would evolve into the modern pawn, knight, bishop, and rook, respectively. Doctors also invented several medical instruments, and even performed operations. The Indian numerals which were the first positional base 10 numeral systems in the world originated from Gupta India. The ancient Gupta text Kama Sutra by the Indian scholar Vatsyayana is widely considered to be the standard work on human sexual behavior in Sanskrit literature.

Aryabhata, a noted mathematician-astronomer of the Gupta period proposed that the earth is round and rotates about its own axis. He also discovered that the Moon and planets shine by reflected sunlight. Instead of the prevailing cosmogony in which eclipses were caused by pseudo-planetary nodes Rahu and Ketu, he explained eclipses in terms of shadows cast by and falling on Earth.[71]

Art and architecture

A tetrastyle prostyle Gupta period temple at Sanchi besides the Apsidal hall with Maurya foundation, an example of Buddhist architecture. 5th century CE.

The Gupta period is generally regarded as a classic peak of North Indian art for all the major religious groups. Although painting was evidently widespread, the surviving works are almost all religious sculpture. The period saw the emergence of the iconic carved stone deity in Hindu art, as well as the Buddha figure and Jain tirthankara figures, the latter often on a very large scale. The two great centres of sculpture were Mathura and Gandhara, the latter the centre of Greco-Buddhist art. Both exported sculpture to other parts of northern India. Unlike the preceding Kushan Empire there was no artistic depiction of the monarchs, even in the very fine Guptan coinage,[72] with the exception of some coins of the Western Satraps, or influenced by them.

The current structure of the Mahabodhi Temple dates to the Gupta era, 5th century CE. Marking the location where the Buddha is said to have attained enlightenment.

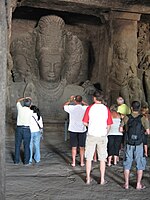

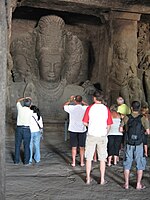

The most famous remaining monuments in a broadly Gupta style, the caves at Ajanta, Elephanta, and Ellora (respectively Buddhist, Hindu, and mixed including Jain) were in fact produced under later dynasties, but primarily reflect the monumentality and balance of Guptan style. Ajanta contains by far the most significant survivals of painting from this and the surrounding periods, showing a mature form which had probably had a long development, mainly in painting palaces.[73] The Hindu Udayagiri Caves actually record connections with the dynasty and its ministers,[74] and the Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh is a major temple, one of the earliest to survive, with important sculpture.[75]

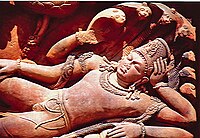

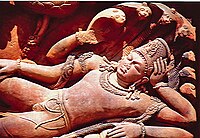

Vishnu reclining on the serpent Shesha (Ananta), Dashavatara Temple 5th century

Buddha from Sarnath, 5–6th century CE

The Colossal trimurti at the Elephanta Caves

Rock-cut temples at Ellora

Painting of Padmapani Cave 1 at Ajanta

References

^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-systems Research. 12 (2): 223. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Gupta Dynasty – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009.

^ N. Jayapalan, History of India, Vol. I, (Atlantic Publishers, 2001), 130.

^ Jha, D.N. (2002). Ancient India in Historical Outline. Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors. pp. 149–173. ISBN 978-81-7304-285-0.

^ ab Raghu Vamsa v 4.60–75

^ Gupta dynasty (Indian dynasty) Archived 30 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved on 2011-11-21.

^ Keay, John (2000). India: A history. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.Kalidasa wrote ... with an excellence which, by unanimous consent, justifies the inevitable comparisons with Shakespeare ... When and where Kalidasa lived remains a mystery. He acknowledges no links with the Guptas; he may not even have coincided with them ... but the poet's vivid awareness of the terrain of the entire subcontinent argues strongly for a Guptan provenance.

^ Vidya Dhar Mahajan 1990, p. 540.

^ Keay, John (2000). India: A history. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.The great era of all that is deemed classical in Indian literature, art and science was now dawning. It was this crescendo of creativity and scholarship, as much as ... political achievements of the Guptas, which would make their age so golden .

^ Gupta dynasty: empire in 4th century Archived 30 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved on 2011-11-21.

^ ab J. C. Harle 1994, p. 87.

^ Trade | The Story of India – Photo Gallery Archived 28 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. PBS. Retrieved on 2011-11-21.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 264–269.

^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 79.

^ Dilip Kumar Ganguly 1987, p. 14.

^ Tej Ram Sharma 1989, p. 39.

^ Dilip Kumar Ganguly 1987, p. 2.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 96.

^ Dilip Kumar Ganguly 1987, pp. 7-11.

^ Dilip Kumar Ganguly 1987, p. 12.

^ Tej Ram Sharma 1989, p. 44.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 82.

^ Tej Ram Sharma 1989, p. 42.

^ R. C. Majumdar 1981, p. 4.

^ Tej Ram Sharma 1989, p. 40.

^ Tej Ram Sharma 1989, pp. 43-44.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 83.

^ Tej Ram Sharma 1989, pp. 49-55.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 86.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, pp. 84–85.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, pp. 79-81.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 85.

^ R. C. Majumdar 1981, pp. 6-7.

^ R. C. Majumdar 1981, p. 10.

^ Tej Ram Sharma 1989, p. 71.

^ Smith, Vincent A. (1999). The Early History of India: From 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan Conquest. Atlantic. p. 289. ISBN 978-81-7156-618-1.

^ The Gupta Polity, pp.199

^ Vidya Dhar Mahajan 1990, p. 487.

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 153–159.

^ Bajpai, K.D. (2004). Indian Numismatic Studies. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. pp. 120–1. ISBN 978-81-7017-035-8.

^ H. C. Raychaudhuri 1923, p. 489.

^ ata shrivikramadityo helya nirjitakhilah Mlechchana Kamboja. Yavanan neechan Hunan Sabarbran Tushara. Parsikaanshcha tayakatacharan vishrankhalan hatya bhrubhangamatreyanah bhuvo bharamavarayate (Brahata Katha, 10/1/285-86, Kshmendra).

^ Kathasritsagara 18.1.76–78

^ Cf:"In the story contained in Kathasarit-sagara, king Vikarmaditya is said to have destroyed all the barbarous tribes such as the Kambojas, Yavanas, Hunas, Tokharas and the, National Council of Teachers of English Committee on Recreational Reading – Sanskrit language.

^ Prasanna Rao Bandela (1 January 2003). Coin splendour: a journey into the past. Abhinav Publications. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-81-7017-427-1. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

^ "Evidence of the conquest of Saurastra during the reign of Chandragupta II is to be seen in his rare silver coins which are more directly imitated from those of the Western Satraps... they retain some traces of the old inscriptions in Greek characters, while on the reverse, they substitute the Gupta type (a peacock) for the chaitya with crescent and star." in Rapson "A catalogue of Indian coins in the British Museum. The Andhras etc...", p.cli

^ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 191–200.

^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, Unesco p.119 sq

^ "Nalanda University Ruins | Nalanda Travel Guide | Ancient Nalanda Site". Travel News India. 5 October 2016. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

^ H. C. Raychaudhuri 1923, p. 510.

^ ab The Huns, Hyun Jin Kim, Routledge, 2015 p.50 sq

^ H. C. Raychaudhuri 1923, p. 516.

^ Sachchidananda Bhattacharya, Gupta dynasty, A dictionary of Indian history, (George Braziller, Inc., 1967), 393.

^ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.220

^ Encyclopaedia of Indian Events & Dates by S. B. Bhattacherje p.A15

^ Columbia Encyclopedia

^ abcde The First Spring: The Golden Age of India by Abraham Eraly p.48 sq

^ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.221

^ A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India p.174

^ Longman History & Civics ICSE 9 by Singh p.81

^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 480. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

^ Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol.3 (inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings) p.362

^ ab Indian Esoteric Buddhism: Social History of the Tantric Movement by Ronald M. Davidson p.31

^ abc A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India by Upinder Singh p.521

^ abc The Gupta Empire by Radhakumud Mookerji p.133 sq

^ Sankalia, Hasmukhlal Dhirajlal (1934). The University of Nālandā. B. G. Paul & co.

^ Sukumar Dutt (1988) [First published in 1962]. Buddhist Monks And Monasteries of India: Their History And Contribution To Indian Culture. George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London. ISBN 978-81-208-0498-2.

^ Vidya Dhar Mahajan 1990, p. 530–1.

^ Murray, H. J. R. (1913). A History of Chess. Benjamin Press (originally published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 978-0-936317-01-4. OCLC 13472872.

^ Thomas Khoshy, Elementary Number Theory with Applications, Academic Press, 2002, p. 567.

ISBN 0-12-421171-2.

^ J. C. Harle 1994, pp. 87-89.

^ J. C. Harle 1994, pp. 118-122, 123-126, 129-135.

^ J. C. Harle 1994, pp. 92-97.

^ J. C. Harle 1994, pp. 113-114.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Ashvini Agrawal (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

Dilip Kumar Ganguly (1987). The Imperial Guptas and Their Times. Abhinav. ISBN 978-81-7017-222-2.

H. C. Raychaudhuri (1923). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. University of Calcutta. ISBN 978-1-4400-5272-9.

J. C. Harle (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

R. C. Majumdar (1981). A Comprehensive History of India. 3, Part I: A.D. 300-985. Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. pp. 17–52. OCLC 34008529.

Tej Ram Sharma (1989). A Political History of the Imperial Guptas: From Gupta to Skandagupta. Concept. ISBN 978-81-7022-251-4.

Vidya Dhar Mahajan (1990). A History of India. State Mutual Book & Periodical Service. ISBN 978-0-7855-1191-5.

External links

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Gupta. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gupta Empire |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gupta Empire. |

- Coins of Gupta Empire

- Photo Feature on Gupta Period Art

Middle kingdoms of India | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline and cultural period | Northwestern India (Punjab-Sapta Sindhu) | Indo-Gangetic Plain | Central India | Southern India | ||

| Upper Gangetic Plain (Kuru-Panchala) | Middle Gangetic Plain | Lower Gangetic Plain | ||||

IRON AGE | ||||||

Culture | Late Vedic Period | Late Vedic Period (Brahmin ideology)[a] Painted Grey Ware culture | Late Vedic Period (Kshatriya/Shramanic culture)[b] Northern Black Polished Ware | Pre-history | ||

6th century BC | Gandhara | Kuru-Panchala | Magadha | Adivasi (tribes) | ||

Culture | Persian-Greek influences | "Second Urbanisation" Rise of Shramana movements Jainism - Buddhism - Ājīvika - Yoga | Pre-history | |||

5th century BC | (Persian rule) | Shishunaga dynasty | Adivasi (tribes) | |||

4th century BC | (Greek conquests) | Nanda empire | ||||

HISTORICAL AGE | ||||||

Culture | Spread of Buddhism | Pre-history | Sangam period (300 BC – 200 AD) | |||

3rd century BC | Maurya Empire | Early Cholas Early Pandyan Kingdom Satavahana dynasty Cheras 46 other small kingdoms in Ancient Thamizhagam | ||||

Culture | Preclassical Hinduism[c] - "Hindu Synthesis"[d] (ca. 200 BC - 300 AD)[e][f] Epics - Puranas - Ramayana - Mahabharata - Bhagavad Gita - Brahma Sutras - Smarta Tradition Mahayana Buddhism | Sangam period (continued) (300 BC – 200 AD) | ||||

2nd century BC | Indo-Greek Kingdom | Shunga Empire Maha-Meghavahana Dynasty | Early Cholas Early Pandyan Kingdom Satavahana dynasty Cheras 46 other small kingdoms in Ancient Thamizhagam | |||

1st century BC | ||||||

1st century AD | Indo-Scythians | Kuninda Kingdom | ||||

2nd century | Kushan Empire | |||||

3rd century | Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom | Kushan Empire | Western Satraps | Kamarupa kingdom | Kalabhra dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) | |

Culture | "Golden Age of Hinduism"(ca. AD 320-650)[g] Puranas Co-existence of Hinduism and Buddhism | |||||

4th century | Kidarites | Gupta Empire Varman dynasty | Kalabhra dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) Kadamba Dynasty Western Ganga Dynasty | |||

5th century | Hephthalite Empire | Alchon Huns | Kalabhra dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) Vishnukundina | |||

6th century | Nezak Huns Kabul Shahi | Maitraka | Adivasi (tribes) | Badami Chalukyas Kalabhra dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) | ||

Culture | Late-Classical Hinduism (ca. AD 650-1100)[h] Advaita Vedanta - Tantra Decline of Buddhism in India | |||||

7th century | Indo-Sassanids | Vakataka dynasty Empire of Harsha | Mlechchha dynasty | Adivasi (tribes) | Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) Pandyan Kingdom(Revival) Pallava | |

8th century | Kabul Shahi | Pala Empire | Pandyan Kingdom Kalachuri | |||

9th century | Gurjara-Pratihara | Rashtrakuta dynasty Pandyan Kingdom Medieval Cholas Pandyan Kingdom(Under Cholas) Chera Perumals of Makkotai | ||||

10th century | Ghaznavids | Pala dynasty Kamboja-Pala dynasty | Kalyani Chalukyas Medieval Cholas Pandyan Kingdom(Under Cholas) Chera Perumals of Makkotai Rashtrakuta | |||

References and sources for table References

Sources

| ||||||