Eutectic system

A phase diagram for a fictitious binary chemical mixture (with the two components denoted by A and B) used to depict the eutectic composition, temperature, and point. (L denotes the liquid state.)

A eutectic system (/juːˈtɛktɪk/ yoo-TEK-tik)[1] from the Greek "ευ" (eu = easy) and "τήξις" (teksis = melting) is a homogeneous mixture of substances that melts or solidifies at a single temperature that is lower than the melting point of either of the constituents.

The separate atomic or chemical species form a joint super-lattice, by striking a unique atomic percentage ratio between the components – as each pure component has its own distinct bulk lattice arrangement. It is only in this atomic or molecular ratio that the eutectic system melts as a whole, at a specific temperature (the eutectic temperature). The super-lattice releases at once all its components into a liquid mixture. The eutectic temperature is the lowest possible melting temperature over all of the mixing ratios for the involved component species.

Upon heating any other mixture ratio, and reaching the eutectic temperature – see the adjacent phase diagram – one component's lattice will melt first, while the temperature of the mixture has to further increase for (all) the other component lattice(s) to melt. Conversely, as a non-eutectic mixture cools down, each mixture's component will solidify (form its lattice) at a distinct temperature, until all material is solid.

The coordinates defining a eutectic point on a phase diagram are the eutectic percentage ratio (on the atomic/molecular ratio axis of the diagram) and the eutectic temperature (on the temperature axis of the diagram).[2]

Not all binary alloys have eutectic points because the valence electrons of the component species are not always compatible,[clarification needed] in any mixing ratio, to form a new type of joint crystal lattice. For example, in the silver-gold system the melt temperature (liquidus) and freeze temperature (solidus) "meet at the pure element endpoints of the atomic ratio axis while slightly separating in the mixture region of this axis".[3]

The term eutectic was coined in 1884 by British physicist and chemist Frederick Guthrie (1833–1886).[4]

Contents

1 Eutectic reaction

2 Non-eutectic compositions

3 Types

3.1 Alloys

3.2 Others

4 Other critical points

4.1 Eutectoid

4.2 Peritectoid

4.3 Peritectic

5 Eutectic calculation

6 See also

7 References

7.1 Bibliography

8 Further reading

Eutectic reaction

Four eutectic structures: A) lamellar B) rod-like C) globular D) acicular.

The eutectic reaction is defined as follows:[5]

- Liquid→coolingeutectic temperatureαsolid solution+βsolid solution{displaystyle {text{Liquid}}{xrightarrow[{text{cooling}}]{text{eutectic temperature}}}alpha ,,{text{solid solution}}+beta ,,{text{solid solution}}}

This type of reaction is an invariant reaction, because it is in thermal equilibrium; another way to define this is the change in Gibbs free energy equals zero. Tangibly, this means the liquid and two solid solutions all coexist at the same time and are in chemical equilibrium. There is also a thermal arrest for the duration of the change of phase during which the temperature of the system does not change.[5]

The resulting solid macrostructure from a eutectic reaction depends on a few factors. The most important factor is how the two solid solutions nucleate and grow. The most common structure is a lamellar structure, but other possible structures include rodlike, globular, and acicular.[6]

Non-eutectic compositions

Compositions of eutectic systems that are not at the eutectic composition can be classified as hypoeutectic or hypereutectic. Hypoeutectic compositions are those with a smaller percent composition of species β and a greater composition of species α than the eutectic composition (E) while hypereutectic solutions are characterized as those with a higher composition of species β and a lower composition of species α than the eutectic composition. As the temperature of a non-eutectic composition is lowered the liquid mixture will precipitate one component of the mixture before the other. In a hypereutectic solution, there will be a proeutectoid phase of species β whereas a hypoeutectic solution will have a proeutectic α phase.[5]

Types

Alloys

Eutectic alloys have two or more materials and have a eutectic composition. When a non-eutectic alloy solidifies, its components solidify at different temperatures, exhibiting a plastic melting range. Conversely, when a well-mixed, eutectic alloy melts, it does so at a single, sharp temperature. The various phase transformations that occur during the solidification of a particular alloy composition can be understood by drawing a vertical line from the liquid phase to the solid phase on the phase diagram for that alloy.

Some uses include:

- NEMA Eutectic Alloy Overload Relays for electrical protection of 3-phase motors for pumps, fans, conveyors, and other factory process equipment.[7]

- Eutectic alloys for soldering, composed of tin (Sn), lead (Pb) and sometimes silver (Ag) or gold (Au) — especially Sn63Pb37 alloy formula for electronics

- Casting alloys, such as aluminium-silicon and cast iron (at the composition of 4.3% carbon in iron producing an austenite-cementite eutectic)

Silicon chips are bonded to gold-plated substrates through a silicon-gold eutectic by the application of ultrasonic energy to the chip. See eutectic bonding.

Brazing, where diffusion can remove alloying elements from the joint, so that eutectic melting is only possible early in the brazing process- Temperature response, e.g., Wood's metal and Field's metal for fire sprinklers

- Non-toxic mercury replacements, such as galinstan

- Experimental glassy metals, with extremely high strength and corrosion resistance

- Eutectic alloys of sodium and potassium (NaK) that are liquid at room temperature and used as coolant in experimental fast neutron nuclear reactors.

Others

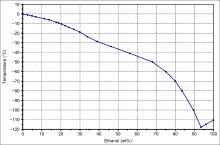

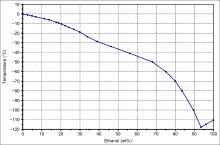

Sodium chloride and water form a eutectic mixture whose eutectic point is −21.2 °C[8] and 23.3% salt by mass.[9] The eutectic nature of salt and water is exploited when salt is spread on roads to aid snow removal, or mixed with ice to produce low temperatures (for example, in traditional ice cream making).- Ethanol–water has an unusually biased eutectic point, i.e. it is close to pure ethanol, which sets the maximum proof obtainable by fractional freezing.

Solid–liquid phase change of ethanol–water mixtures

- "Solar salt", 60% NaNO3 and 40% KNO3, forms a eutectic molten salt mixture which is used for thermal energy storage in concentrated solar power plants.[10] To reduce the eutectic melting point in the solar molten salts, calcium nitrate is used in the following proportion: 42% Ca(NO3)2, 43% KNO3, and 15% NaNO3.

Lidocaine and prilocaine—both are solids at room temperature—form a eutectic that is an oil with a 16 °C (61 °F) melting point that is used in eutectic mixture of local anesthetic (EMLA) preparations.

Menthol and camphor, both solids at room temperature, form a eutectic that is a liquid at room temperature in the following proportions: 8:2, 7:3, 6:4, and 5:5. Both substances are common ingredients in pharmacy extemporaneous preparations.[11]

Minerals may form eutectic mixtures in igneous rocks, giving rise to characteristic intergrowth textures exhibited, for example, by granophyre.[12]

- Some inks are eutectic mixtures, allowing inkjet printers to operate at lower temperatures.[13]

Other critical points

Eutectoid

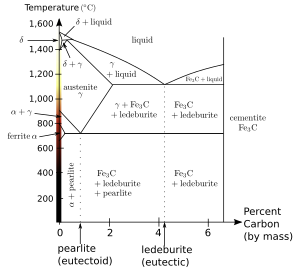

Iron-carbon phase diagram, showing the eutectoid transformation between austenite (γ) and pearlite.

When the solution above the transformation point is solid, rather than liquid, an analogous eutectoid transformation can occur. For instance, in the iron-carbon system, the austenite phase can undergo a eutectoid transformation to produce ferrite and cementite, often in lamellar structures such as pearlite and bainite. This eutectoid point occurs at 727 °C (1,341 °F) and about 0.76% carbon.[14]

Peritectoid

A peritectoid transformation is a type of isothermal reversible reaction that has two solid phases reacting with each other upon cooling of a binary, ternary, ..., n{displaystyle n!}

Peritectic

Peritectic transformations are also similar to eutectic reactions. Here, a liquid and solid phase of fixed proportions react at a fixed temperature to yield a single solid phase. Since the solid product forms at the interface between the two reactants, it can form a diffusion barrier and generally causes such reactions to proceed much more slowly than eutectic or eutectoid transformations. Because of this, when a peritectic composition solidifies it does not show the lamellar structure that is found with eutectic solidification.

Such a transformation exists in the iron-carbon system, as seen near the upper-left corner of the figure. It resembles an inverted eutectic, with the δ phase combining with the liquid to produce pure austenite at 1,495 °C (2,723 °F) and 0.17% carbon.

Gold-aluminium phase diagram (German). Top axis title reads "Weight-percent Gold", lower axis title reads "Atomic-percent Gold"

At the peritectic decomposition temperature the compound, rather than melting, decomposes into another solid compound and a liquid. The proportion of each is determined by the lever rule. In the Al-Au phase diagram, for example, it can be seen that only two of the phases melt congruently, AuAl2 and Au2Al , while the rest peritectically decompose.

Eutectic calculation

The composition and temperature of a eutectic can be calculated from enthalpy and entropy of fusion of each components.[17]

The Gibbs free energy G depends on its own differential:

- G=H−TS⇒{H=G+TS(∂G∂T)P=−S⇒H=G−T(∂G∂T)P.{displaystyle G=H-TSRightarrow {begin{cases}H=G+TS\left({frac {partial G}{partial T}}right)_{P}=-Send{cases}}Rightarrow H=G-Tleft({frac {partial G}{partial T}}right)_{P}.}

Thus, the G/T derivative at constant pressure is calculated by the following equation:

- (∂G/T∂T)P=1T(∂G∂T)P−1T2G=−1T2(G−T(∂G∂T)P)=−HT2.{displaystyle left({frac {partial G/T}{partial T}}right)_{P}={frac {1}{T}}left({frac {partial G}{partial T}}right)_{P}-{frac {1}{T^{2}}}G=-{frac {1}{T^{2}}}left(G-Tleft({frac {partial G}{partial T}}right)_{P}right)=-{frac {H}{T^{2}}}.}

The chemical potential μi{displaystyle mu _{i}}

- μi=μi∘+RTlnaia≈μi∘+RTlnxi.{displaystyle mu _{i}=mu _{i}^{circ }+RTln {frac {a_{i}}{a}}approx mu _{i}^{circ }+RTln x_{i}.}

At the equilibrium, μi=0{displaystyle mu _{i}=0}

- μi=μi∘+RTlnxi=0⇒μi∘=−RTlnxi.{displaystyle mu _{i}=mu _{i}^{circ }+RTln x_{i}=0Rightarrow mu _{i}^{circ }=-RTln x_{i}.}

Using[clarification needed] and integrating gives

- (∂μi/T∂T)P=∂∂T(Rlnxi)⇒Rlnxi=−Hi∘T+K.{displaystyle left({frac {partial mu _{i}/T}{partial T}}right)_{P}={frac {partial }{partial T}}left(Rln x_{i}right)Rightarrow Rln x_{i}=-{frac {H_{i}^{circ }}{T}}+K.}

The integration constant K may be determined for a pure component with a melting temperature T∘{displaystyle T^{circ }}

- xi=1⇒T=Ti∘⇒K=Hi∘Ti∘.{displaystyle x_{i}=1Rightarrow T=T_{i}^{circ }Rightarrow K={frac {H_{i}^{circ }}{T_{i}^{circ }}}.}

We obtain a relation that determines the molar fraction as a function of the temperature for each component:

- Rlnxi=−Hi∘T+Hi∘Ti∘.{displaystyle Rln x_{i}=-{frac {H_{i}^{circ }}{T}}+{frac {H_{i}^{circ }}{T_{i}^{circ }}}.}

The mixture of n components is described by the system

- {lnxi+Hi∘RT−Hi∘RTi∘=0,∑i=1nxi=1.{displaystyle {begin{cases}ln x_{i}+{frac {H_{i}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{i}^{circ }}{RT_{i}^{circ }}}=0,\sum limits _{i=1}^{n}x_{i}=1.end{cases}}}

- {∀i<n⇒lnxi+Hi∘RT−Hi∘RTi∘=0,ln(1−∑i=1n−1xi)+Hn∘RT−Hn∘RTn∘=0,{displaystyle {begin{cases}forall i<nRightarrow ln x_{i}+{frac {H_{i}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{i}^{circ }}{RT_{i}^{circ }}}=0,\ln left(1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}x_{i}right)+{frac {H_{n}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{n}^{circ }}{RT_{n}^{circ }}}=0,end{cases}}}

which can be solved by

- [Δx1Δx2Δx3⋮Δxn−1ΔT]=[1/x10000−H1∘RT201/x2000−H2∘RT2001/x300−H3∘RT2⋮⋱⋱⋱⋱⋮00001/xn−1−Hn−1∘RT2−11−∑i=1n−1xi−11−∑i=1n−1xi−11−∑i=1n−1xi−11−∑i=1n−1xi−11−∑i=1n−1xi−Hn∘RT2]−1.[lnx1+H1∘RT−H1∘RT1∘lnx2+H2∘RT−H2∘RT2∘lnx3+H3∘RT−H3∘RT3∘⋮lnxn−1+Hn−1∘RT−Hn−1∘RTn−1∘ln(1−∑i=1n−1xi)+Hn∘RT−Hn∘RTn∘]{displaystyle {begin{array}{c}left[{begin{array}{*{20}c}{Delta x_{1}}\{Delta x_{2}}\{Delta x_{3}}\vdots \{Delta x_{n-1}}\{Delta T}\end{array}}right]=left[{begin{array}{*{20}c}{1/x_{1}}&0&0&0&0&{-{frac {H_{1}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\0&{1/x_{2}}&0&0&0&{-{frac {H_{2}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\0&0&{1/x_{3}}&0&0&{-{frac {H_{3}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\vdots &ddots &ddots &ddots &ddots &{vdots }\0&0&0&0&{1/x_{n-1}}&{-{frac {H_{n-1}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{-{frac {H_{n}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\end{array}}right]^{-1}.left[{begin{array}{*{20}c}{ln x_{1}+{frac {H_{1}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{1}^{circ }}{RT_{1}^{circ }}}}\{ln x_{2}+{frac {H_{2}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{2}^{circ }}{RT_{2}^{circ }}}}\{ln x_{3}+{frac {H_{3}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{3}^{circ }}{RT_{3}^{circ }}}}\vdots \{ln x_{n-1}+{frac {H_{n-1}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{n-1}^{circ }}{RT_{n-1}^{circ }}}}\{ln left({1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}right)+{frac {H_{n}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{n}^{circ }}{RT_{n}^{circ }}}}\end{array}}right]end{array}}}

See also

Azeotrope, or constant boiling mixture- Freezing-point depression

References

^ "Eutectic". Merriam-Webster Dictionary..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Smith & Hashemi 2006, pp. 326–327

^ "Collection of Phase Diagrams". www.crct.polymtl.ca.

^ Guthrie, Frederick (1884) "On eutexia", Philosophical Magazine, 5th series, 17 : 462–482. From p. 462: "The main argument of the present communication hinges upon the existence of compound bodies, whose chief characteristic is the lowness of their temperatures of fusion. This property of the bodies may be called Eutexia †, the bodies possessing it eutectic bodies or eutectics (εύ τήκειν)."

^ abc Smith & Hashemi 2006, p. 327.

^ Smith & Hashemi 2006, pp. 332–333.

^ "Operation of the Overloads". Retrieved 2015-08-05.

^ Muldrew, Ken; Locksley E. McGann (1997). "Phase Diagrams". Cryobiology—A Short Course. University of Calgary. Retrieved 2006-04-29.

^ Senese, Fred (1999). "Does salt water expand as much as fresh water does when it freezes?". Solutions: Frequently asked questions. Department of Chemistry, Frostburg State University. Retrieved 2006-04-29.

^ "Molten salts properties". Archimede Solar Plant Specs.

^ Phaechamud, Thawatchai; Tuntarawongsa, Sarun; Charoensuksai, Purin (October 2016). "Evaporation Behavior and Characterization of Eutectic Solvent and Ibuprofen Eutectic Solution". AAPS PharmSciTech. 17 (5): 1213–1220. doi:10.1208/s12249-015-0459-x. ISSN 1530-9932. PMID 26669887.

^ Fichter, Lynn S. (2000). "Igneous Phase Diagrams". Igneous Rocks. James Madison University. Retrieved 2006-04-29.

^ Davies, Nicholas A.; Beatrice M. Nicholas (1992). "Eutectic compositions for hot melt jet inks". US Patent & Trademark Office, Patent Full Text and Image Database. United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved 2006-04-29.

^ "Iron-Iron Carbide Phase Diagram Example". Archived from the original on 2008-02-16.

^ IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, Electronic version. "Peritectoid Reaction" Retrieved May 22, 2007.

^ Numerical Model of Peritectoid Transformation. Peritectoid Transformation Retrieved May 22, 2007. Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

^ International Journal of Modern Physics C, Vol. 15, No. 5. (2004), pp. 675–687.

Bibliography

Smith, William F.; Hashemi, Javad (2006), Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering (4th ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-295358-6.

Further reading

| Look up eutectic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Askeland, Donald R.; Pradeep P. Phule (2005). The Science and Engineering of Materials. Thomson-Engineering. ISBN 0-534-55396-6.

Easterling, Edward (1992). Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys. CRC. ISBN 0-7487-5741-4.

Mortimer, Robert G. (2000). Physical Chemistry. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-508345-9.

Reed-Hill, R. E.; Reza Abbaschian (1992). Physical Metallurgy Principles. Thomson-Engineering. ISBN 0-534-92173-6.

Sadoway, Donald (2004). "Phase Equilibria and Phase Diagrams" (PDF). 3.091 Introduction to Solid State Chemistry, Fall 2004. MIT Open Courseware. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2005-10-20. Retrieved 2006-04-12.

![text{Liquid} xrightarrow[text{cooling}]{text{eutectic temperature}} alpha ,, text{solid solution} + beta ,, text{solid solution}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ddd335b6ed20e9308b5e9588ea94d3759fe9fbff)

![{displaystyle {begin{array}{c}left[{begin{array}{*{20}c}{Delta x_{1}}\{Delta x_{2}}\{Delta x_{3}}\vdots \{Delta x_{n-1}}\{Delta T}\end{array}}right]=left[{begin{array}{*{20}c}{1/x_{1}}&0&0&0&0&{-{frac {H_{1}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\0&{1/x_{2}}&0&0&0&{-{frac {H_{2}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\0&0&{1/x_{3}}&0&0&{-{frac {H_{3}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\vdots &ddots &ddots &ddots &ddots &{vdots }\0&0&0&0&{1/x_{n-1}}&{-{frac {H_{n-1}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{frac {-1}{1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}}&{-{frac {H_{n}^{circ }}{RT^{2}}}}\end{array}}right]^{-1}.left[{begin{array}{*{20}c}{ln x_{1}+{frac {H_{1}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{1}^{circ }}{RT_{1}^{circ }}}}\{ln x_{2}+{frac {H_{2}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{2}^{circ }}{RT_{2}^{circ }}}}\{ln x_{3}+{frac {H_{3}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{3}^{circ }}{RT_{3}^{circ }}}}\vdots \{ln x_{n-1}+{frac {H_{n-1}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{n-1}^{circ }}{RT_{n-1}^{circ }}}}\{ln left({1-sum limits _{i=1}^{n-1}{x_{i}}}right)+{frac {H_{n}^{circ }}{RT}}-{frac {H_{n}^{circ }}{RT_{n}^{circ }}}}\end{array}}right]end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b406139e6e1704cc3d0d07f5cce485c55b01d475)